At around 7.30 a.m. on February 24 this year, 43-year-old Pandi Venkaiah drank pesticide on his farm in Penugolanu village. He was alone, his family was at home. At around 9 a.m., a few other farmers came across his dead body in the field.

Venkaiah’s loans had spiralled to more than Rs. 17 lakhs after a crushing loss of over Rs. 10 lakhs in just the 2016 agricultural season. He owned an acre of land and leased seven more at an annual tenancy rate of Rs. 30,000 per acre. In September 2016, he sowed Rs. 1 lakh worth of chilli seeds on four acres and cotton on the remaining four. “He invested 10 lakhs on the crop,” says Seetha, 35, his wife. Part of the loan was taken from private moneylenders, and some of it was a gold loan on Seetha’s few ornaments in the bank.

By December 2016, documents at the collector’s office show, 87 farmers from Penugolanu village in Gampalagudem mandal of Krishna district in Andhra Pradesh realised that their chilli crop was failing. They had all purchased seeds from two local nurseries. “The mirchi crop on [a total of] 162 acres failed. All the investment and labour just went down the drain,” says 26-year-old Vadderapu Tirupathi Rao.

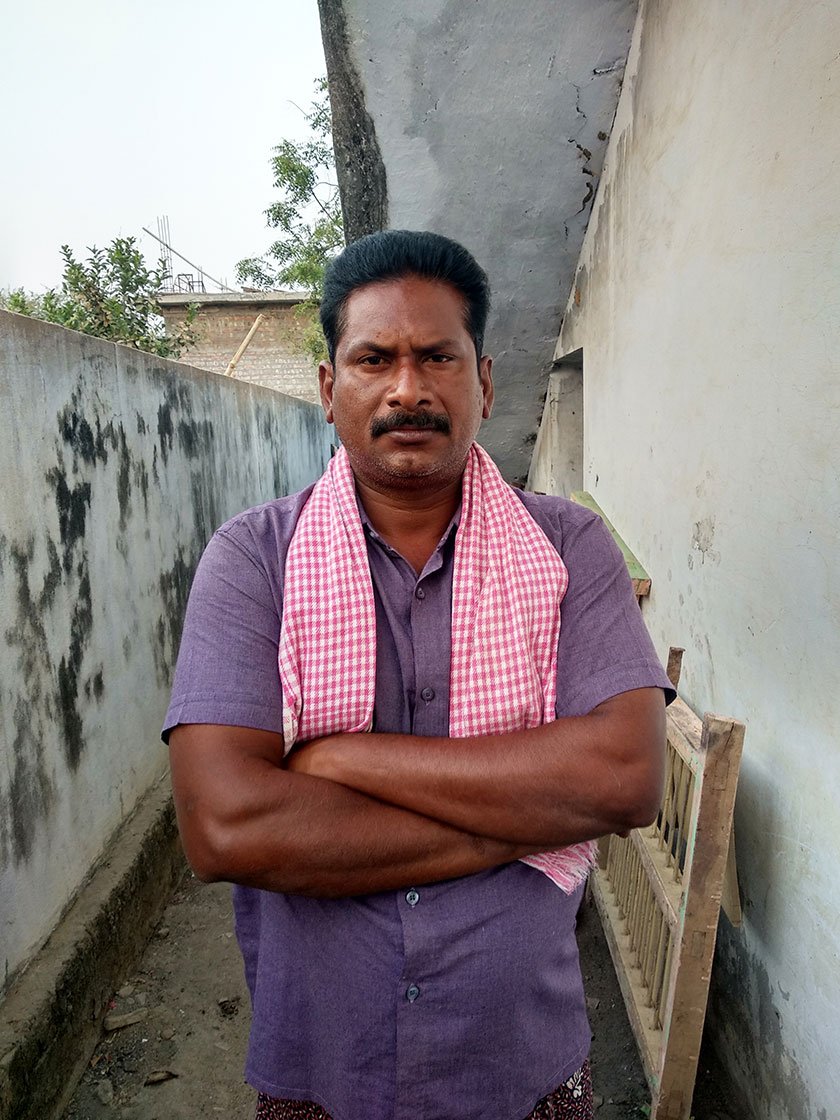

Seetha's husband Pandi Venkaiah committed suicide in February. Right: Banala Naga Poornayya, who suffered losses too, is leading the farmers' agitation for compensation

Three months before Venkaiah’s suicide, on November 22, 2017, Tirupathi Rao and two other farmers, Banala Naga Poornayya, 32, and Ramayya, 35, had tried to kill themselves in Amaravati, right in front of the new state assembly building. On that day, farmers who had suffered serious losses because of poor quality seeds from the two nurseries had marched to Amaravati to protest against the government’s inability to hold the nursery owners culpable. The police arrested the farmers when they reached the assembly. Feeling helpless and enraged, the three consumed pesticide right there.

Until 2016, mirchi had usually been a profitable crop in this border region of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, known for its chillis. Most farmers here grow the teja mirchi . In 2016, the market price was an all-time high, even touching Rs. 15,000 per quintal, around double the usual. The high rates in the first half of 2016 increased the demand for mirchi seeds in September-October 2016. And a bollworm attack on the cotton crop forced even more farmers to try their luck with mirchi .

But then the yield turned out to be really poor – for the first time ever in Penugolanu that farmers can recall – because of the bad seeds sold by the two nurseries to cash in on the huge demand.

Farmers in this region usually buy high-yielding hybrid mirchi seeds from nurseries, who in turn purchase them from agro-companies. Non-hybrid varieties no longer grow well here because of the impact on the soil of excessive use of hybrids and fertilisers, among other reasons. And for the same reason, neither can the farmers save a portion of their robust indigenous varieties from their own crops for next year’s sowing – as they did in the past, says Nagaboina Rangarao of the All India Kisan Sabha. In 2016, because of the high demand, two local nurseries sold low-yielding non-hybrid seeds to 87 farmers. The seeds all look the same, so the farmers went ahead and sowed them. But the yields turned out to be stunningly lower.

The average

mirchi

yield per acre in this region is 35 to 40 quintals. But last year the highest yield was just 3 quintals on Ramayya’s farm

The average per-acre mirchi yield in this region is 35 to 40 quintals. “But last year [September 2016 to January 2017], the 10 acres I cultivated together produced just 20 quintals of mirchi . The highest yield was 3 quintals (per acre) on Ramayya’s farm,” says Poornayya. He had taken the 10 acres on lease in 2016, but the failed mirchi crop forced him to cut back. “I took just 3 acres on lease this year [September 2017 to January 2018] since I already have a debt of over 12 lakh rupees,” he adds.

Mirchi is a labour intensive crop, on which cultivators invest Rs. 2.5 to 3 lakhs per acre – on seeds, fertiliser and the painstaking sowing and picking. “The farmers had already spent over 1.5 lakh per acre before they realised that the crop was failing due to the spurious seeds,” Poornayya adds. “On top of that, most of us are tenant farmers and we have to pay tenancy to the landlords irrespective of the failed crop.”

The tenant farmers did not have access to institutional credit because they don’t have Loan Eligibility Cards from the state’s Agriculture Department. The card enables farmers who don’t own any land to access some sort of institutional credit. One such tenant farmer, Devara Nagarjuna, 50, says, “I now have a total debt of 10 lakh at an interest rate of 60 per cent, part of it from the very people who sold us the seeds.” Devara lost Rs. 5 lakhs during the 2016-17 agricultural season due to the bad seeds. “They take our fingerprints on empty promissory notes while giving seeds, pesticides and fertilisers and write any [inflated] amount,” he says. “Since they are also the middlemen who purchase our produce, they deduct the debt and interest and pay us back the rest.”

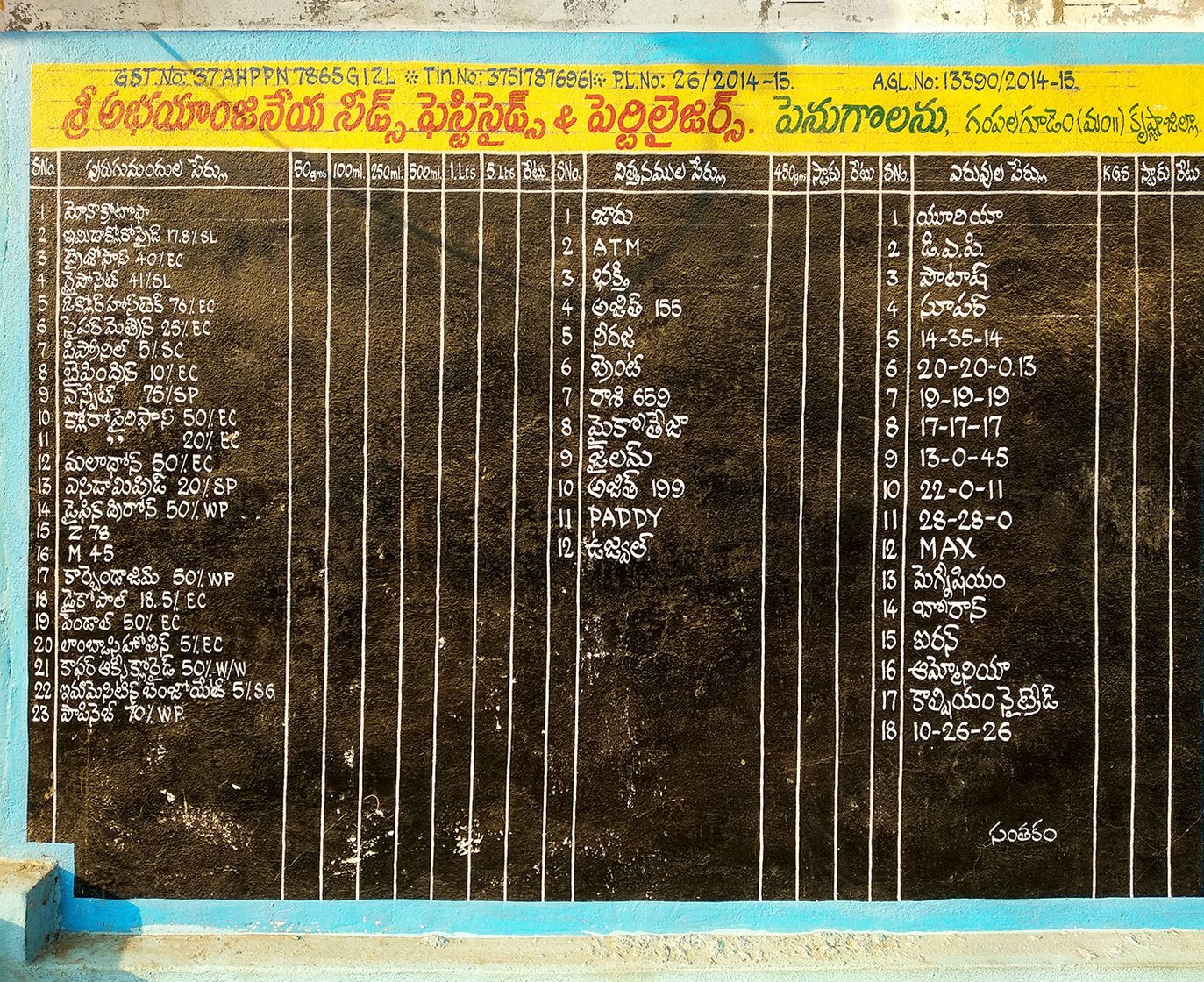

Abhayanjaneya Nursery in Penugolanu is one of the two nurseries that sold farmers the bad seeds. Right: Its stock list of seeds, fertilisers and pesticides

The ‘they’ he is referring to are the nursery owners. The seeds had been sold by the Abhayanjaneya Nursery owned by Nagalla Murali, and the Lakshmi Tirupathamma Nursery, owned by Eduru Satyanarayana Reddy. These outlets sell seeds, fertilisers and pesticides, and also give high-interest crop loans to farmers who don’t have access to institutional credit; the nursery owners are also often the agents for the mirchi market yard in Guntur.

Murali is the village president of the Telugu Desam Party and a close aide of Devineni Uma Maheswara Rao, Minister for Water Resources and Irrigation; Satyanarayana is a leader of the Yuvajana Shramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP), formed by Jaganmohan Reddy. He is also an aide of Kokkiligadda Rakshana Nidhi, YSRCP member of the legislative assembly from Tiruvuru (the constituency in which Penugolanu is located).

Since December 2016 the 87 farmers – along with a few others in solidarity – have organised dharnas and protests in front of the mandal revenue office in Gampalagudem, the revenue divisional office in Nuzvid, the collector’s office in Machilipatnam, and the Agriculture Department’s offices in Guntur and in Amaravati. Later this month, they are planning a padayatra , to continue the agitation.

Since the failed crop, the farmers have protested numerous times. On March 12, 2018, they sat in a dharna outside the Agriculture Department in Guntur

The failed mirchi crop has brought them together under the Andhra Pradesh Tenant Farmers’ Association, affiliated to the All India Kisan Sabha. “We are fighting for compensation from the nurseries,” says Poornayya, who is leading the agitation against the nursery owners. He spent 24 days in Nuzvid sub-jail and 11 cases have been registered against him.

In March 2017, the collector of Krishna district, B. Lakshmikantham, ordered an investigation by a District Level Compensation Committee comprising scientists and agricultural officers. The committee’s report states that the seeds are indeed bogus and that the nursery owners should pay a compensation of Rs. 91,000 per acre of lost crop. Both the nurseries together owe Rs. 2.13 crores to the 87 farmers.

In January 2018, the collector ordered the nurseries to pay the compensation. But the amount remains elusive even after the farmer’s next crop was harvested in early 2018 – planted with seeds from other nurseries. When I spoke to B. Lakshmikantham, he told me, "We have submitted our response to the High Court. Once the court clears it, we will use the Revenue Recovery Act and seize the properties of the owners and pay the compensation to the farmers."

“We have met the agricultural minister [S. Chandramohan Reddy] four times, the minister in-charge of the district [Devineni Uma] twice, and the collector eight times. We lost count of the number of times we met the mandal revenue officer and agricultural officer,” says Tirupathi Rao, the young farmer who attempted suicide. “We were arrested many times when we went to protest. It’s been more than 18 months since our crops failed and we are yet to receive even one rupee of compensation.”

Devara Nagarjuna (left) lost Rs. 5 lakhs due to the bad seeds. Tirupathi Rao (right) tried to kill himself during one of the protests

When I ask Ch. Rangaiah, the revenue divisional officer of Nuzvid division, which covers Penugolanu village, about the compensation, he says, "After the collector ordered the compensation of Rs. 91,000 per acre, the nurseries approached the high court. Since the matter is sub-judice now, we will have to wait for the court to rule."

The

lawyer arguing the case on behalf of the farmers in the Andhra Pradesh high

court, Potturi Suresh Kumar, says, “The liability to check the usage of

spurious seeds lies with the state. Why isn’t there a mechanism or a law to

govern nurseries? A Nursery Act should be enacted and all the nurseries must be

brought under its ambit.”

But Venkaiah lost his life in the absence of any such protection. And the other farmers are still reeling. “No one should be born as a farmer in this country. We feed the nation and every government claims that they are farmer friendly, but we are remembered only during elections,” says Tirupathi Rao. “What other option did we have to make our voice heard? And what hope of justice? It was a spontaneous decision to commit suicide despite the thoughts of my wife and three-year-old child… It’s better to die than be hounded by moneylenders every day.” With that, 26-year-old Rao bursts into tears.