The last time Usha Devi saw Dharmendra Ram, he was a shriveled remain of his even normally shrunken self. “He emitted a cry, heaved and then went silent. I couldn’t even get him one last cup of tea,” she says.

And thus ended the life of Usha’s 28-year-old husband. He died sick and hungry – without a ration card. Dharmendra Ram had the all-important Aadhaar card that could verify his identity at the ration shop. But it was useless without an actual ration card.

Dharmendra’s death in August 2016 drew many visitors and much attention to his village of Dharauta in Allahabad’s Mauaima block. The local media demanded that district officials visit. The Village Development Officer and the lekhpal (village accountant) were suspended. A clutch of reliefs was announced. (Among them, Rs. 30,000 under the National Family Benefit Scheme and a parcel of five biswa or 570 square metres, of farmland). Local politicians rushed to this village of barely 500 households. His wife was suddenly found eligible for the state government’s disability pension of Rs. 500.

Usha, who struggles with hearing, is partially blind, and whose right limbs are significantly smaller than her left, has faint memories of how it had all unfolded. She does remember one official (‘ bada saheb’ ) at whose feet she fell. “ Kuch toh madad karo [give some help at least],” she recalls saying to him.

Usha Devi (left) lost her husband to hunger because they didn't have a ration card. Their sister-in-law, Bhootani Devi (right), says acquiring the card is complicated

That official was tehsildar Ramkumar Verma, who had inspected the couple’s home. Local media would later quote him as saying he had not found even a single grain of food in the house. On Usha’s plea, he had fished in his pocket and handed Rs. 1,000 to her just before she fainted from a mix of exhaustion and hunger.

Pancham Lal, the present lekhpal of Soraon tehsil (in which Dharauta is located) explains this act as part of the swift measures taken by the administration. “It was an unfortunate incident,” he says. He believes the process of procuring a ration card and connecting it to the Aadhaar is pain free. “People can do all this online. There is a private shop which does it in the village for Rs. 50. But then there must be the will to do so. Did we not issue an Antyodaya card to his wife in just 15 days?” he asks.

The verification of ration cards through the Aadhaar number is upheld as one of the greatest successes of this identification process. According to the government’s own figures, more than four in every five ration cards issued under the National Food Security Act have been linked to Aadhaar.

In theory, Dharmendra’s possession of an Aadhaar ID

should have made it easier for him to acquire a ration card. In reality, the

process for acquiring any of these, including and perhaps especially the

filling-in of online forms, is too complex for the Dharmendra Rams of the

world. Getting help isn’t simple, either. “Not-my-department” is the standard

official reply they face.

Usha Devi makes cow dung cakes (left) at her brother Lalji Ram's home (right) in Dandoopur village, where she spends most of her time

Dharauta village pradhan (elected panchayat chief) Teeja Devi declares, “My husband took him on a motorcycle to get enrolled. It is not the pradhan but the Panchayat Secretary who is responsible for the ration card.”

The illiterate Dharmendra, described by neighbours as careless and lazy, was never likely to decipher these entanglements. Introduced in 2009, and since then linked to the entitlement of a plethora of government schemes, Aadhaar is a difficult detail to understand even for those who have it.

Among them is Dharmendra’s sister-in-law Bhootani (his elder brother Nanhe’s wife) who says, “The government card is a good thing. I have it, but I don’t know it fully. Too many papers are required. We helped Dharmendra as and when we could, but had our limitations.”

Dharmendra’s only income came from dancing at

weddings. Work was intermittent, and the best he could make from a night’s

performance never exceeded Rs. 500. There was a small patch of land his father

had divided between him and Nanhe. Dharmendra’s bit was rocky and yielded

little. He would often flag down passersby to ask for help. Usha begged for

food. Sometimes people called her when there were leftovers. “I felt no shame,”

she emphasises, not recalling any time in her marriage of 12 years when food

was abundant. “Sometimes when he would have money, we would buy tomatoes and

pulses,” she says.

Sunita Raj (left) gave Usha's family some leftovers, but couldn't do more.

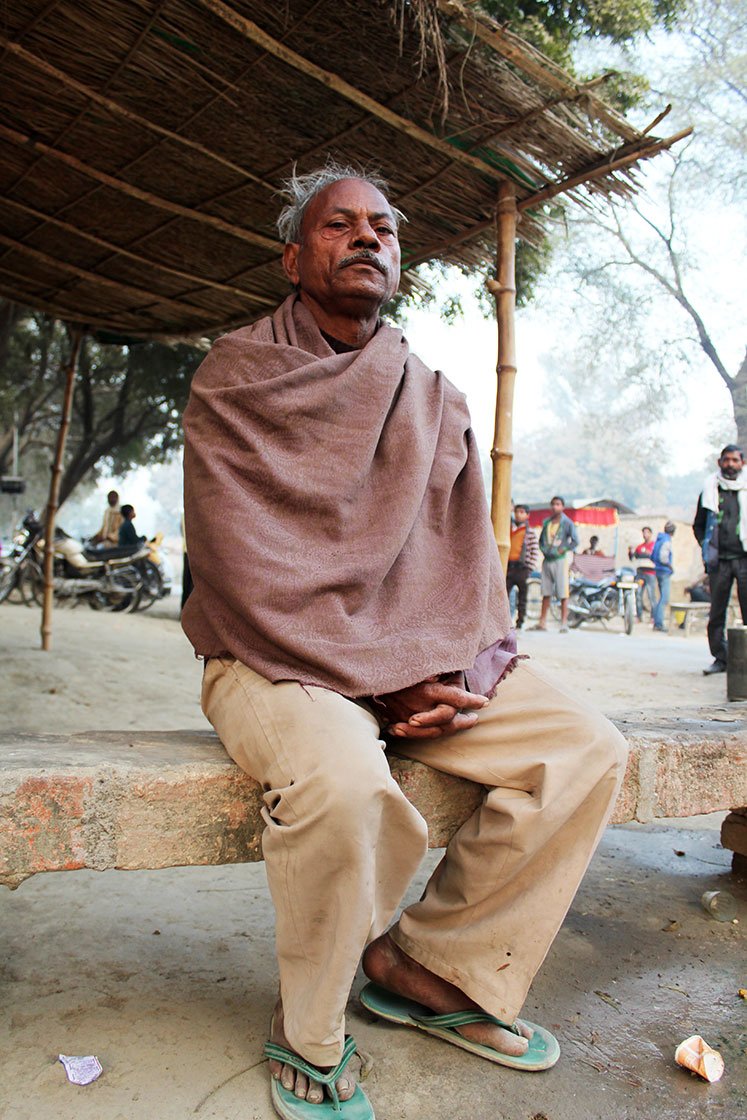

Ram Gautam (right) says Dharmendra’s death brought government officials to their village

The fact that a man died of hunger in their midst still evokes a mix of emotions in Dharauta. Across the road from Dharmendra’s house is the robust-looking pink home of 50-year-old Sunita Raj. While she was one of those who gave food to Usha intermittently, she says full-time support was impossible. “When you look into our house, there is nothing. These are just the outer walls. We lost everything in the five years that my [late] husband was unwell. Now my only son is unemployed. For all you know, even I might die of hunger,” she says. That fear arises from the fact that Sunita does not have an Aadhaar with the local address and therefore her name is not on the family’s ration card. “I had an Aadhaar in Pune where my husband worked as a labourer. I was told it would help in getting medicines, but that did not happen,” she shrugs.

Ram Asrey Gautam, 66, another neighbour, says Dharmendra’s death achieved the impossible. “No official gave any importance to our village. Then the sub-divisional magistrate, block development officer, tehsildar , all suddenly appeared. Our village was blessed by just that.”

Since Dharmendra’s death, Usha spends most of her time at her brother Lalji Ram’s home in Dandoopur village (19 kilometres from Dharauta). “When Dharmendra was alive the villagers did not help him. Now they are jealous that she has [570 square metres of] fertile land. I look after it for her as she is mentally feeble,” says the father of four.

For Usha, the land and the financial assistance are just details. “My husband died for a small card. It cannot be worth that much,” she says.