When Kanhaiyalal jumped off from the engine driver’s cabin with a pair of red and green flags in his hands, we got off the slowing train, too. We’d been waiting for that. What we did not expect was for him to shoot off across the next 200 metres like a sprinter. We ran behind him, stumbling on the uneven surface. Kanhaiyalal darted towards an unmanned level crossing and, waving his red flag, quickly shut and locked the railway gate there. Then he turned towards the train and waved the green flag. The train moved forward, passed the locked gate – and stopped again. Kanhaiyalal opened up the gate and raced back to the driver’s cabin, with us closely behind.

He could do this up to 16 times over a distance of 68 kilometres, one-way. “It’s what I do. I’m the mobile gatekeeper,” he says. It brings back a whole, old meaning to the word 'mobile'. This is the South East Central railway in Chhattisgarh state. And we’re on the 232 Down Dhamtari Passenger, better known as the ‘Labour Train'. It ferries hundreds of migrant labourers from nearby villages flocking to Raipur city in a desperate search for work. The full journey from Dhamtari to Telibandha in Raipur takes three hours and five minutes, with nine station halts on the route. And there are some 19 ‘gates’ or level crossings of which just two or three are manned.

“My job is to open and shut the gates,” says Kanhaiyalal Gupta. “Earlier there used to be gatekeepers for these crossings, but now I have been appointed as the mobile gatekeeper. I used to be a gangman but was promoted to this post, which I’ve held for two years. I enjoy my work.” He is certainly dedicated and hard-working (and would be earning less than Rs. 20,000 a month).

'My job is to open and shut the gates', says Kanhaiyalal Gupta. 'I enjoy my work'

In the early stations on the route, a ‘mobile gatekeeper’ can board one of the rear compartments after seeing the train through at one of the gates. With the train yet to fill up, he can sit comfortably. As the train nears Raipur, though, he hasn’t a chance of squeezing in. So he has to run up to the driver’s cabin and stand there till the next gate.

Once, the railways themselves employed many more here. Today, there are astonishing numbers of unfilled vacancies. Kanhaiyalal’s job is no 'innovation'. Just an attempt to keep workforce numbers down. Safety-wise all those 16 crossings require gatekeepers. And, in the official count of the Railways, there are more than 30,000 level crossings in the country, of which over 11,500 are unmanned.

Casualties at level crossings account for nearly 40 per cent of all train accidents and two-thirds of all fatalities on railway lines. Disasters at manned level crossings are rare. The railways’ response has been to shut down as many unmanned crossings as it can rather than staff them with gatekeepers. Or to create 'mobile gatekeepers' like Kanhaiyalal to do the work of several men.

On the 232 Down Dhamtari Passenger, though, the chances of mishaps are less. It is a narrow gauge train, one of the rare few still in harness. And it travels rather slowly, as indeed it should, with so many people clambering on. However, the reasons Kanhaiyalal’s job exists are all about reducing workforce numbers.

As the train nears Raipur, he hasn’t a chance of squeezing in and has to run up to the driver’s cabin and stand there till the next gate

“The sanctioned strength of the Indian railways is 13.4 lakh personnel,” says Venu P. Nair, general secretary of the National Railway Mazdoor Union. “But there are nearly 2 lakh vacancies. And more every year. That’s the trend. In the '70s, we had 17 lakh workers and 5 lakh casual labourers. And today this – although the number of passenger trains has nearly doubled since then. So too the number of stations, lines and booking counters. Yet, there has been a pronounced decline in jobs in the last 20 years. This is risky and wrong.” The Indian railways run more than 12,000 trains, carrying some 23 million passengers daily.

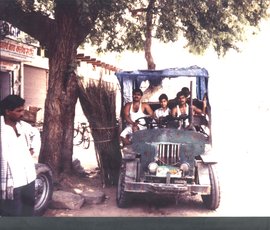

The capacity of Dhamtari’s ‘Labour Train’ with seven coaches is under 400. There are probably twice that number aboard and hanging on at the sides and back, and even in the spaces between coaches. “You should see the train by the time we near Raipur,” says one worker. “Then it gets full up at the top as well.”

The passengers are entertained by the sight of the two of us, with video cameras, haring after Kanhaiyalal at each unmanned level crossing. “It’s a film shooting,” declares one, wedged between two compartments. “They’re from Bollywood.” “So who’s the hero?” yells his companion. “Never mind the damn hero,” shouts a third. “Show us the heroine.”

But they talk to us patiently at the stations. Every one of them a migrant seeking work in the city. They are from the scores of villages in the region where agriculture is in shambles. Why take the train, we ask. With this sort of crowding, you must be exhausted by the time you reach Raipur. “The train ticket from Dhamtari to Raipur costs just 20 rupees. The bus fare for the same route is 65 to 70 rupees, more than thrice as much. Journeying both ways by bus could cost more than half the 200-250 rupees we earn in a day.”

Backseat riders, on the 232 Down Dhamtari Passenger

“In the morning train,” explains engine driver Venugopal, “the maximum passengers are indeed labourers. People from the interior villages board this train and go to Raipur for daily wage work. And return in the evening train every day.”

“It’s very hard,” says Rohit Nawrangey, at the Kendri station. He is a labourer who does that journey every now and then, despite owning a tiny cycle repair shop in Kendri village. “You can’t make enough here to survive,” he says.

We’re back on the train, with Kanhaiyalal totally focused on his work, readying for the next gate. “Open and shut,” he says, smiling.

A version of this story was run on BBC News online (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-29057792) in English and Hindi, on September 22, 2014.