Joaquim Fernandes’s mobile phone rings incessantly when he is home for his lunch break. He does not carry his phone to work, and his clients have come to learn that this is the best time to reach him. The 53-year-old is a highly sought-after coconut plucker in Parra, a village in north Goa.

The state has 25,000 hectares under coconut plantations and an acute shortage of pluckers. This keeps old timers like Fernandes busy through the week. He cycles every morning and afternoon to coconut groves up to 12 kilometres away, and climbs about 50 trees a day. The number of days he works varies from month to month. In the monsoon season (June to September) he climbs trees only on days when the sun has sufficiently dried the trunks. The rest of the year, Fernandes makes his ascent every day, as do most coconut pluckers in Goa. He charges Rs. 50 per tree; that can work out to a daily earning of Rs. 2,500.

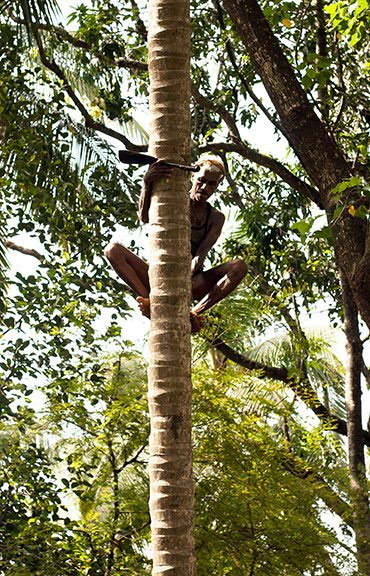

Joaquim Fernandes takes advantage of a dry spell during the monsoon to climb a few coconut trees

In the summer, coconuts dry quickly. The heat also saps Fernandes’s energy faster. The coconut groves are attended to by him once a month and the number of trees he climbs reduces to 30 a day.

The government of Goa initiated a biannual programme in 2013 to train young men to pluck coconuts. Successful candidates are recruited by the state, and farmers can approach the government to avail of their services. Twenty such pluckers are provided incentives in the form of insurance and medical facilities, apart from a monthly salary of approximately Rs 15,000 a month plus incentives. Officials say the demand for the pluckers’ services is so high that they are unable to meet it with the existing supply of trained men.

It is a challenging time. Given the shortage of pluckers, farmers are increasingly hesitant to grow new crop. There is a push by the state government to popularise the mechanical coconut cutter – a device made of steel pipes that serve as climbing support. It includes a safety rope that spans the climbers’ waist and tree trunk. But the old timers are not too impressed. They can climb four trees, they claim, in the time it takes the machine to scale one.

Left: A clutch of thin ropes made of coconut fibre is the only aid used to climb a tree. Right: The axe is the coconut plucker's most important tool. Fernandes has carved a wooden handle for it

In Goa, coconut-plucking skills were traditionally handed down from father to son. After Class 10, Fernandes’s son completed a technical course and worked in the services industry. He aspired to work in Kuwait, where his uncles are based, and had no interest in his family’s traditional occupation. After many years of struggling to find his feet, he did consider joining the tough but lucrative field of coconut-plucking. But a plucker has low social standing in Goa, and there are few takers for a groom. He finally joined the crew of a cruise ship-liner.

David Pereira, from the coastal village of Calangute in north Goa, has a similar story to tell. The 55-year-old fell off a coconut tree five years ago and fractured his leg, so he restricts himself to climbing 20 trees a day.

David Pereira prefers to carry the axe in his hand while he climbs a 30-foot tree

He prefers coconuts as payment for his services. His wife sells them at the weekly market in Mapusa, nine kilometres away. The coconuts retail at Rs. 7-11, depending on size and seasonal demand. Pereira’s son works overseas on a ship. “My son says I don’t have to do this work as he is earning now. But my body will become stiff if I sit at home and do nothing,” he says.

Although he continues to climb coconut trees, he regrets the loss of a skill he learnt from his father as a young boy. “I have forgotten how to tie the intricate knots involved in toddy tapping. If I knew how to extract toddy from coconut trees, it would have been good as there are no toddy tappers in Calangute anymore,” he says.

If a bunch is not entirely ripe, the plucker uses his hands to harvest only the mature nuts

Pandu Gundu Naik often accompanies Pereira to large coconut groves. A native of Belgaum district in Karnataka, Naik has been climbing trees for the last 20 years. When he first came to Goa, he worked as a daily wager, trimming grass and overgrown trees. He saw an opening in coconut plucking and learnt the skill by watching locals. Naik has helped five others from Belgaum enter this occupation, but now even migrant workers are not interested in plucking coconuts. “They prefer working in hotels, as this job involves hard work and is dangerous,” he says.

Goa's coconut trees have an average annual yield of 80-100 nuts

Fernandes also sells coconuts on behalf of farmers. He husks the fruit at home and sells it to the women who retail them in Mapusa every Friday. The husks are sold as firewood too. However, there have been fewer and fewer takers for this by-product. Over the years, households, schools, local bakeries and other kitchens in the villages have gradually moved to gas-fuelled stoves. But Fernandes continues to have a steady clientele among some households and small scale industries that still use husk as firewood.

A pile of husks lies outside his home, neatly covered with a thick plastic sheet to protect against the rain. This year was particularly bad for sales; it was a lean season on all counts.

During the monsoons, Fernandes does not climb trees too often because moss makes the trunks slippery. Instead, he goes fishing in local streams and estuaries. He takes the highs and lows of the occupation in his stride. “I was born to do this,” he says, shrugging.

Left: Women gather coconuts and carry them to the collection point. Right: Most pluckers now prefer to be paid in cash; in the past they were paid in coconuts