“The impact of felling 130,721 trees will be negligible.”

That is what a senior forest department official, the Regional Chief Conservator of Forests, Sambalpur Division, wrote in February 2014. He was recommending that 2,500 acres of forestland in the villages of Talabira and Patrapali, on the border of Odisha’s Sambalpur and Jharsuguda districts, be handed over for a coal mine.

The residents of the two villages haven’t seen these documents in English, drafted by forest officials, that culminated in the forest clearance for the Talabira II and III Open Cast Coal Mine in March 2019. But the people here could not agree less with the official’s opinion – who is, ironically, a designated ‘conservator’.

Over the past two weeks, thousands of trees (how many exactly, remains unclear) have been felled to smoothen the path for mining. The villagers say no notice was given. And many of them – in this village of 2,150 people (Census 2011) – are heartbroken, angry and intimidated that a forest they say they have conserved for decades is being torn down before their eyes, with the help of the police and the state armed forces personnel.

Left: The road to Patrapali village winds through dense community-conserved forests. Right: In t he mixed deciduous forests of Talabira village, these giant sal and mahua trees lie axed to the ground

The most immediate impact on the ground at the moment is the tree felling. The destruction began before dawn on December 5, villagers say. Manas Salima, a young man in Mundapada, a predominantly Munda Adivasi hamlet of Talabira, says, “We had barely woken up when they suddenly came and started cutting trees. Word spread, and villagers rushed to stop it, but there was heavy police deployment all around.”

“Almost 150-200 of us gathered and decided to go and meet the collector to ask him to stop this massacre of our trees,” says another Mundapada resident, Fakira Budhiya. “But we were told that whoever goes against the company, or tries to stop their work, will face cases.”

Talabira and Patrapali are sprawling villages located amidst dense mixed deciduous forests – and the green canopy provides instant relief on the hot December afternoon when I visited. The Jharsuguda region with multiple coal mines, sponge iron plants and other industries, records some of Odisha’s highest temperatures each year.

In the villages here, where the major communities include Munda and Gond Adivasis, the people mainly depend on cultivating paddy and vegetables, and on procuring forest produce. Beneath their lands lie rich seams of coal.

Left: Suder Munda says of the tree felling, 'We feel like our loved ones are dying'. Centre: Bimla Munda says the forest is a vital source of survival for them, and they have not awarded consent to the coal mining on the land. Right: Achyut Budhia is among the villagers who would serve on patrol duty to protect the forests – a tradition of community protection called thengapalli

“The forest gives us mahul [ mahua ], sal sap, firewood, mushrooms, roots, tubers, leaves, and grass to make and sell brooms,” says Bimla Munda. “How can the forest department say that cutting over 1 lakh trees will have no impact?”

The Talabira II and III coal mine was awarded to the public sector undertaking Neyveli Lignite Corporation Limited, which in 2018 gave a contract to develop and operate the mine to Adani Enterprises Limited (AEL). In a statement to the Press Trust of India (reported in the media at that time), AEL said that the mine would generate revenues of over Rs. 12,000 crores.

It is to get to this coal that the giant sal and mahua trees now lie axed to the ground in the forests of Talabira village. In a large clearing some distance away, hundreds of freshly logged trees are piled up. An Adani company employee at the site, who declined to give his name, said “7,000 trees have been cut so far.” He then refused to respond to any further questions, and only said, “it would not be right” to provide even a name and contact for a person in the company who would speak to the media.

On the road leading to the villages, we saw a group of Odisha State Armed Force men, and asked why they were there. One of them said, “Because trees are being cut.” He said security personnel were deployed in sections of the forest where tree cutting was underway. While we were speaking, one of his colleagues called someone on his cell phone to report our presence in the village.

Left: While a forest department signboard in Patrapali advocates forest protection, officials have issued a clearance for the coal mine, noting that the effect of cutting of 1.3 lakh trees 'will be negligible'. Centre: Bijli Munda of Mundapada, Talabira, with the brooms she makes with forest produce, which she will sell for Rs. 20-25 each. Right: Brooms drying outside houses here; these are just one of the many forest products from which villagers make a livelihood

According to the forest clearance documents submitted to the central government by the Forest and Environment Department of Odisha, the mine (II and III) will cover a total of 4,700 acres of land, and displace 1,894 families, including 443 Scheduled Caste families and 575 Scheduled Tribe families.

“We believe 14,000-15,000 trees have already been cut,” says Bhakatram Bhoi, “and it is still going on.” He is president of the Forest Rights Committee in Talabira. (These are village-level committees constituted under the Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006 to plan and monitor FRA-related activities, including conservation and the filing of forest rights claims.) “Even I cannot tell you how many trees they have cut,” he says. “The administration and company are doing all this, keeping us villagers completely in the dark, since we have been opposing this from Day 1.” That is, since 2012, when the villagers first wrote to the district administration about their FRA rights.

Rina Munda, a resident of Mundapada, adds, “Our ancestors originally lived in these forests and protected them. We have learnt to do the same. Every family would contribute three kilos of rice or money for thengapalli [a forest protection tradition in Odisha whereby community members patrol forests to prevent timber felling and smuggling].”

“And now we are not even being allowed to go into the very forests we have protected and nurtured,” says Suder Munda, with a pained expression, as villagers gather around the local school to discuss how to resist the destruction. She adds, “We are feeling great sadness looking at how they are cutting our trees. I feel like our loved ones are dying.”

Left: Across the villages, many homes have vegetable farms adjoining homesteads. Right: Many like Hursikes Buriha also depend on paddy cultivation

The villagers emphasise they have been conserving the forests since decades. “Where was the government then?” asks an elderly Suru Munda. “Now that the company wants it, the government is saying the forest is theirs, and we should back off.” Achyut Budhia, another elderly man, who villagers say was among those who served on patrol duty for several years, adds, “I had tears in my eyes when I saw the felled trees. We protected them like our children.”

“Many of us have not been able to sleep at night since this tree cutting began,” says Hemant Rout, a member of the Forest Rights Committee in Talabira village.

Ranjan Panda, a Sambalpur-based environmentalist, who works on issues of climate change and water, says the villagers' efforts to save the forests are particularly significant because Jharsuguda and the Ib Valley region are among the major pollution hotspots in the country. "It doesn't make any sense to build new coal mines and power plants in an area already suffering from severe water scarcity, heat and pollution due to excessive concentration of mining, power and industrial activities," he says. “Chopping off 130,721 full grown natural tree species in this location will further aggravate the multiple stresses of the people and the ecology, making it an inhabitable place.”

Many villagers express this view too, and refer to the rising temperatures in the region. Vinod Munda says, “It will become impossible to live here, if the forest is destroyed. If a villager cuts a tree, we would be put in jail. Then how is the company cutting so many trees, with the support of the police?”

Left: Patrapali sarpanch Sanjukta Sahu with a map of the forestlands which the village has claimed in 2012 under the Forest Rights Act. The administration has still not processed the claim. Centre: Villagers here also have documents from 2012 when they filed community forest claims. Right: People in Talabira show copies of their written complaint about the forgery of gram sabha resolutions awarding consent for the forest clearance

The road to neighbouring Patrapali village winds through dense sal forest. Here, the sawing machines are yet to reach, and residents say they will not allow a single tree to be cut. “If the administration uses force against us, you might see another Kalinganagar”, said Dilip Sahu, “because this entire affair is illegal.” He is referring to the death of 13 Adivasis in 2006 in police firing during protests against the acquisition of land by the state government for a steel plant by Tata Steel Ltd in the state’s coastal district of Jajpur.

The Forest Rights Act states that forest clearance – that is, ‘diverting’ forestland for non-forest uses such as mining – can be awarded only after certain procedures have been followed, including these: first, the villages where forestland is to be diverted have to hold gram sabhas and award or withhold their prior informed consent to the proposed diversion, after all relevant details have been placed before them. Second, there should be no pending individual or community forest rights claims on the land to be diverted.

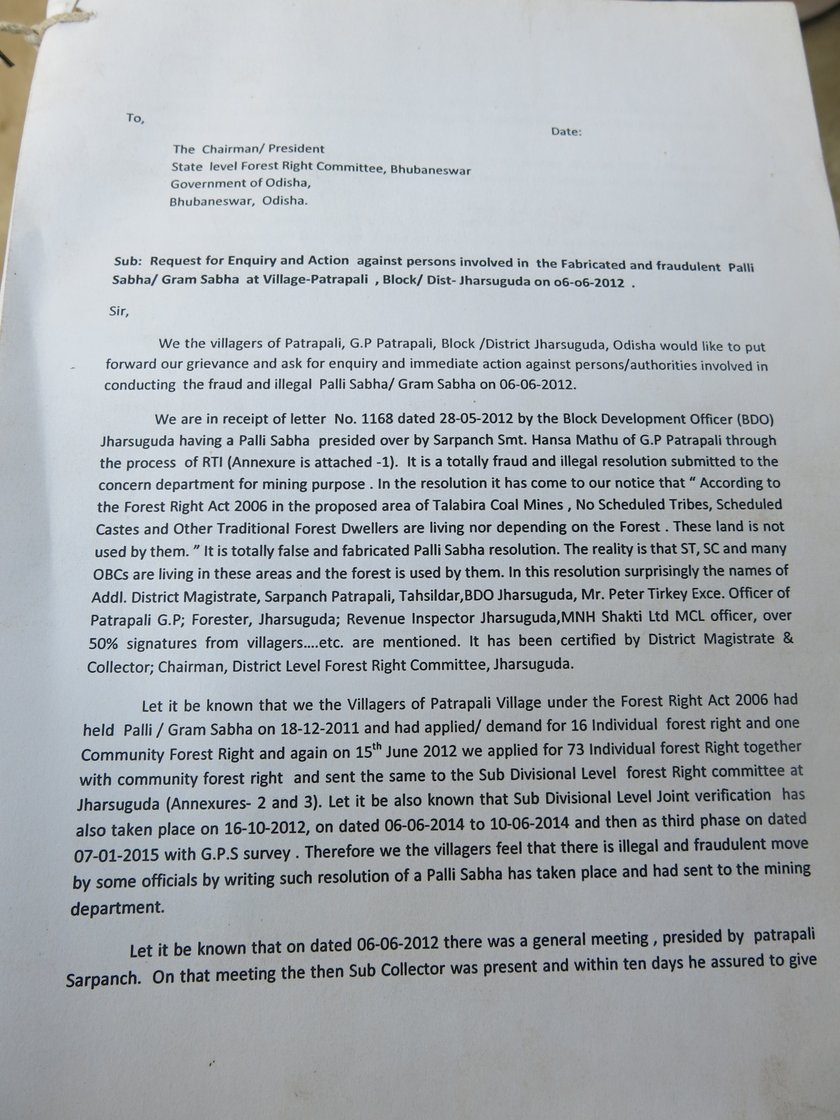

Sanjukta Sahu, sarpanch of Patrapali and president of the village Forest Rights Committee, says the gram sabha resolutions, on the basis of which the central Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change awarded forest clearance to the mine, “are forgeries.” Taking out the gram sabha register to show us, she adds, “Our village has never consented to handing over 700 hectares for coal mining. No way. To the contrary, as far back as 2012, we filed a community forest rights claim under the Forest Rights Act for 715 acres of land. The administration has still not processed our claim in seven years, and now we are learning that the company has got the forest. How can that happen?.”

Dilip Sahu of Patrapali says that over 200 households in the village are families who were displaced by the Hirakud dam in Sambalpur district, around 50 kilometres from Patrapali, the mid-1950s. “If this forest is given to coal mining, we will be displaced again. Should we live our entire lives in displacement, caught between dams and mines?.”

Left: The villagers say income from forest produce helped them build this high school in the village. Right: In a large clearing, under the watch of company staff, hundreds of freshly logged trees are piled up

Residents of Talabira too allege that the

gram sabha

consent resolution of their village has been forged for the forest clearance. They show their written complaints about this sent in October to several authorities across the state government. “It is all done through forgery. We have never given our consent to this forest being cut,” says Sushma Patra, a ward member. Rout said, “On the contrary, our Talabira Gramya Jungle Committee wrote to the collector on May 28, 2012, to award recognition to our rights to the forest under the FRA, and we have submitted a copy of this in our written complaint to the authorities about the consent forgery.”

Kanchi Kohli, senior researcher, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, who has studied the Talabira forest clearance documents says, "In general, forest diversion processes have been extremely opaque. Affected people hardly ever have access to inspection reports and recommendations for approval. The Talabira case is symptomatic of this problem. It is only when tree felling activity took place that villagers got a sense of the scale of the mine expansion on forest areas whether historical rights persist."

A reading of the documents, Kohli adds, “clearly reveals casual site inspection reports and piecemeal appraisals. The impact of felling 1.3 lakh trees is recorded as being negligible and never questioned. The gram sabha resolutions have not been verified by the forest advisory committee of the environment ministry. In all, there appear to be serious legal lacunae in the forest diversion process."

The authorities must listen to the villagers' protests, adds Ranjan Panda. "Coal is the biggest climate culprit and the entire world is trying to phase out from coal fired power plants to mitigate impacts of climate change."

“The government does not make any effort to publicise the Forest Rights Act among people in the villages. We filed claims with our own effort. And we have protected this forest from before there was any law,” says Dilip Sahu. “Today the government claims that we villagers have consented to giving our forests to the company. I want to then ask them, ‘If you have our consent, why do you have to deploy so much police force in our villages for the company to cut our trees?”

Addendum: Adani Enterprises has clarified that it has not carried out any felling of trees in the Talabira coal mine region. The above article has therefore been updated on January 9, 2020, to reflect that position.