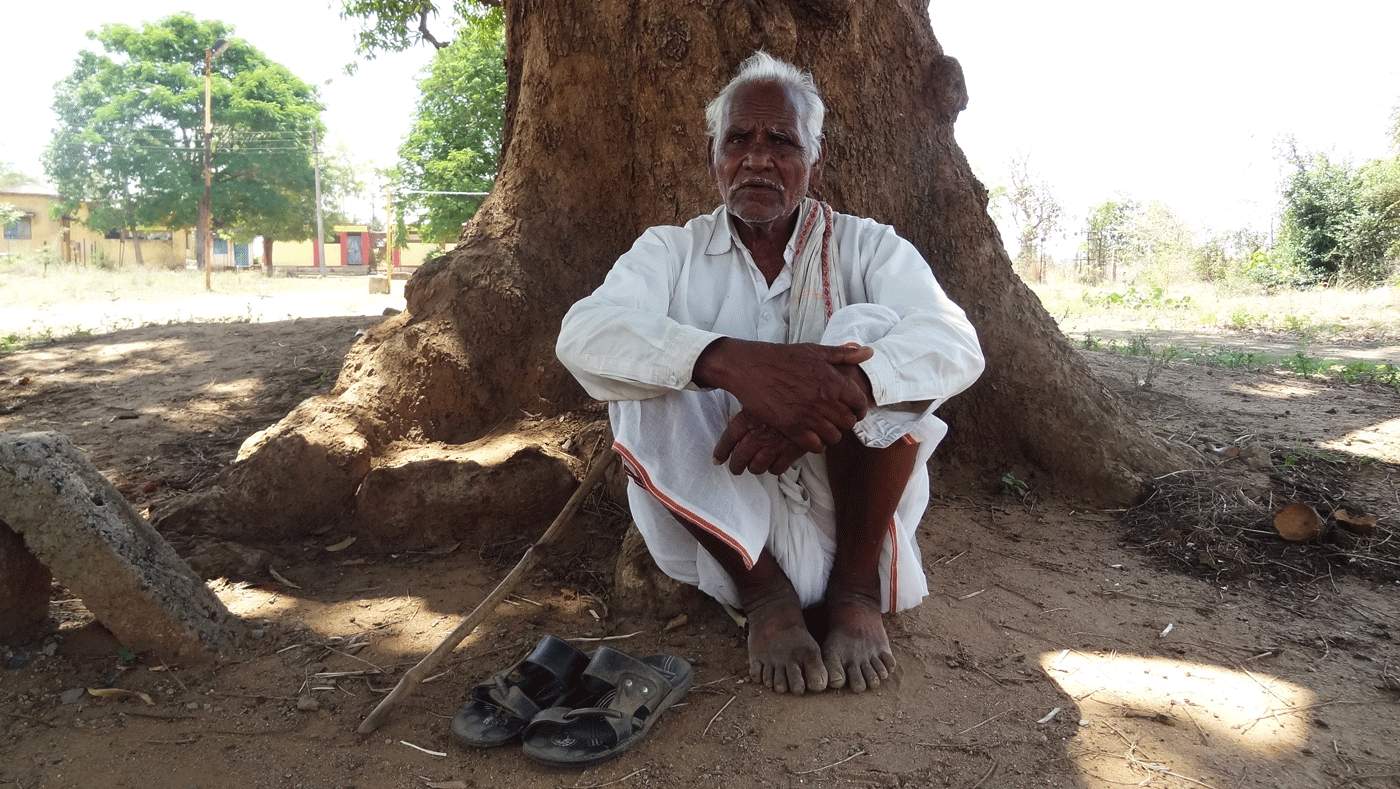

The tree was planted by his grandfather. “It’s older than me,” says Mahadev Kamble, sitting in its shade. And the only one that remains on his now-barren two-acre aamrai (mango orchard).

The lone tree speaks of why Kamble and others in Baranj Mokasa village say that on April 11 they will vote out Hansraj Ahir, the four-time Lok Sabha Member of Parliament from Chandrapur district of eastern Maharashtra, and minister of state for Home Affairs in the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance government.

All the other trees in Kamble’s orchard were cut when his land was acquired for a coal mine. The project, one of many that have sprung up in this region over the last decade, has devastated Baranj Mokasa (listed as Barang Mokasa in Census 2011) by taking over all its land and property, as well as livelihoods.

And it has left the village’s nearly 1,800 residents in uncertainty – though Baranj Mokasa was acquired for the project, the people have not yet been rehabilitated.

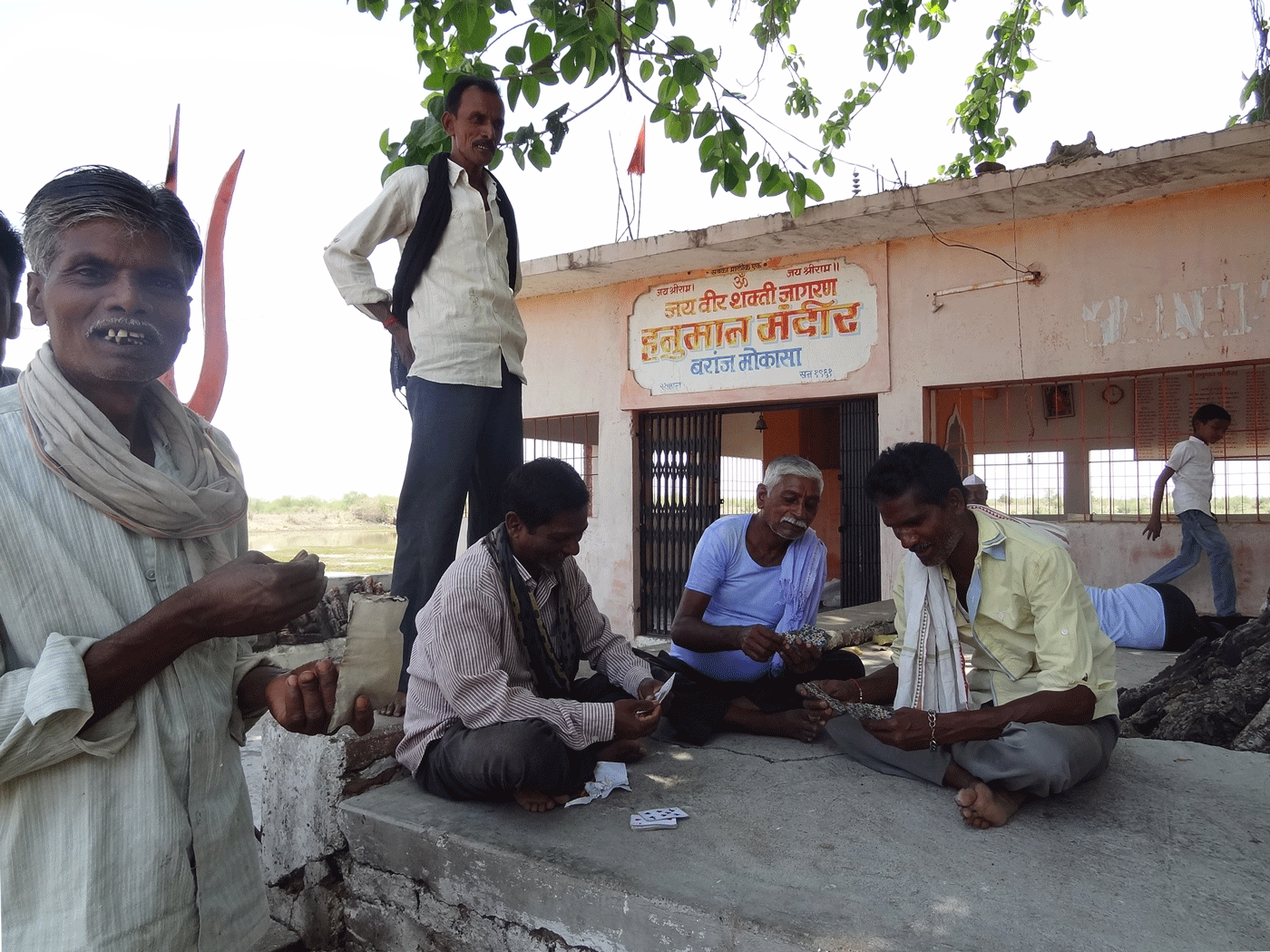

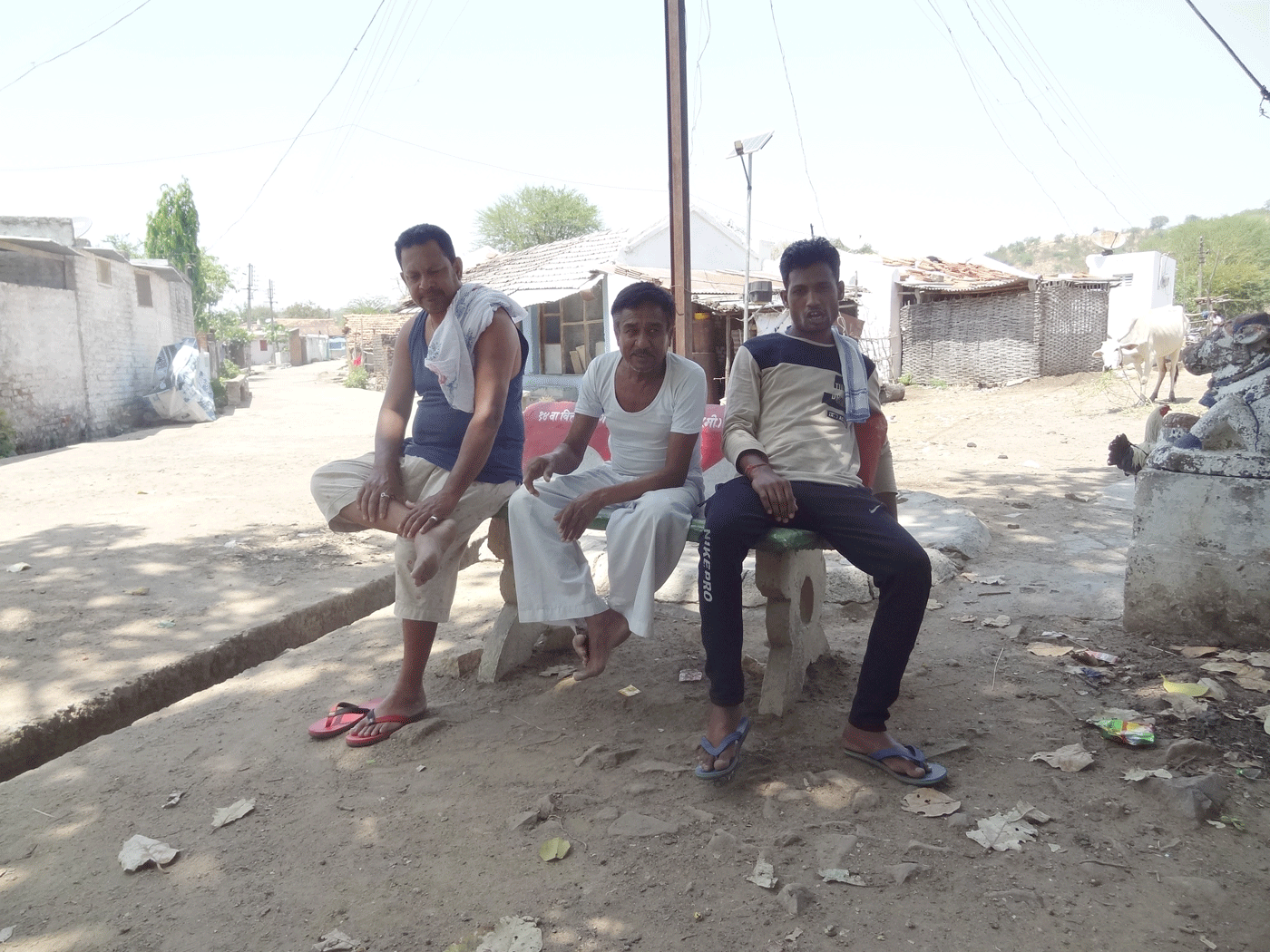

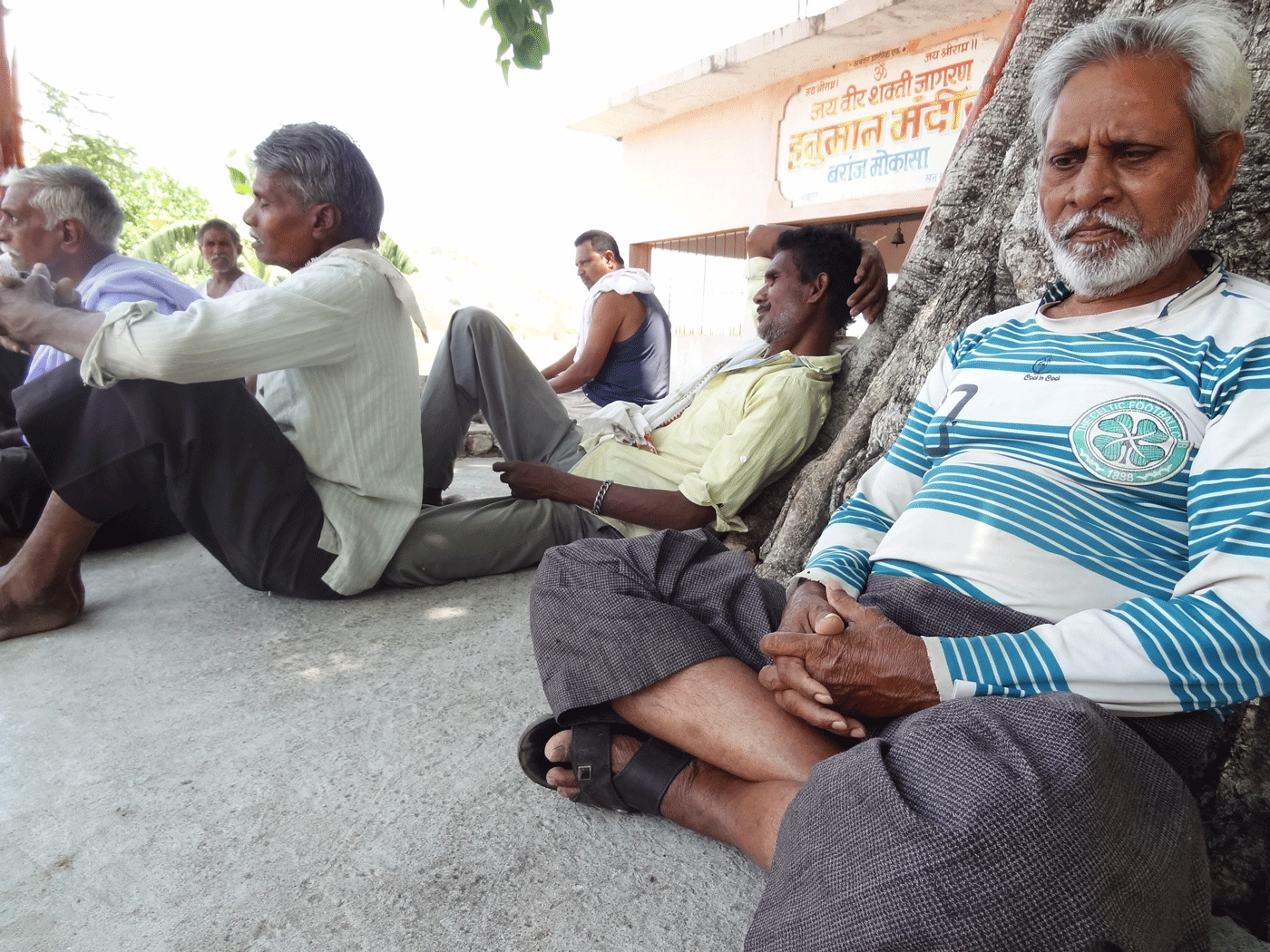

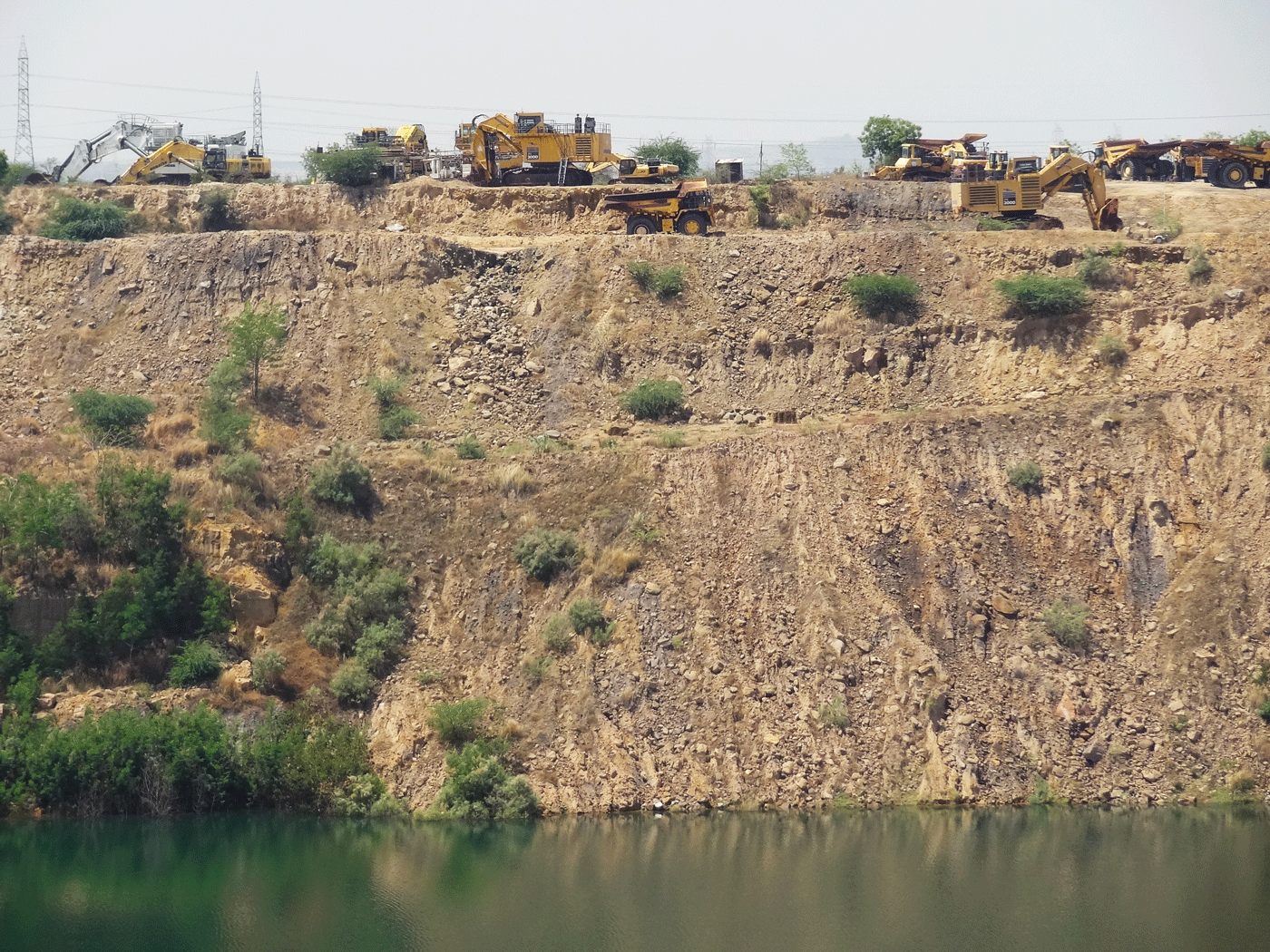

Baranj Mokasa lost over 500 hectares to the coal mine. Many now while away their time in the absence of any work

In 2003, the Karnataka Power Corporation Limited (KPCL), a state government entity, won the lease for the Baranj coal mines for captive use – that is, the mined coal would be used only for its own purpose – in this case, for power generation in Karnataka. The KPCL gave the operational lease to the Eastern Mining and Trading Agency (EMTA), one of India’s biggest private coal mine firms, by forming a joint venture called the Karnataka-EMTA Company Limited (KECL).

By 2008, KECL had acquired 1457.2 hectares spread over seven villages including Baranj Mokasa and neighbouring Chek Baranj. Baranj Mokasa lost around 550 hectares, of which 500 hectares is the coal mine, and the remaining land was acquired for roads, dumps, offices and other purposes. The mines have a reserve of roughly 68 million metric tons reserve – or an estimated extraction of 2.5 million tonnes per year.

Around 50 villages with a total population of 75,000-100,000 have been similarly displaced by public and private sector mines in Chandrapur district in the past 15 years, shows data compiled by Pravin Mote of the Nagpur-based Centre for People’s Collective.

'Money got distributed. They bribed some of our own to get our land and houses. Relatives and families fought among themselves. The village bled'

KECL opted to directly buy the land, without state mediation. In Baranj Mokasa, the villagers received Rs. 4 to 5 lakhs per acre, depending on the location and quality of their plots, and Rs. 750 per square foot for houses and other properties.

But they demanded a proper rehabilitation package – better rates for the land, resettlement at a new village away from the mine, and permanent jobs for at least one member of the displaced family. Though EMTA is a private company, it was a joint venture with a state entity, and the government can mediate to ensure fair compensation.

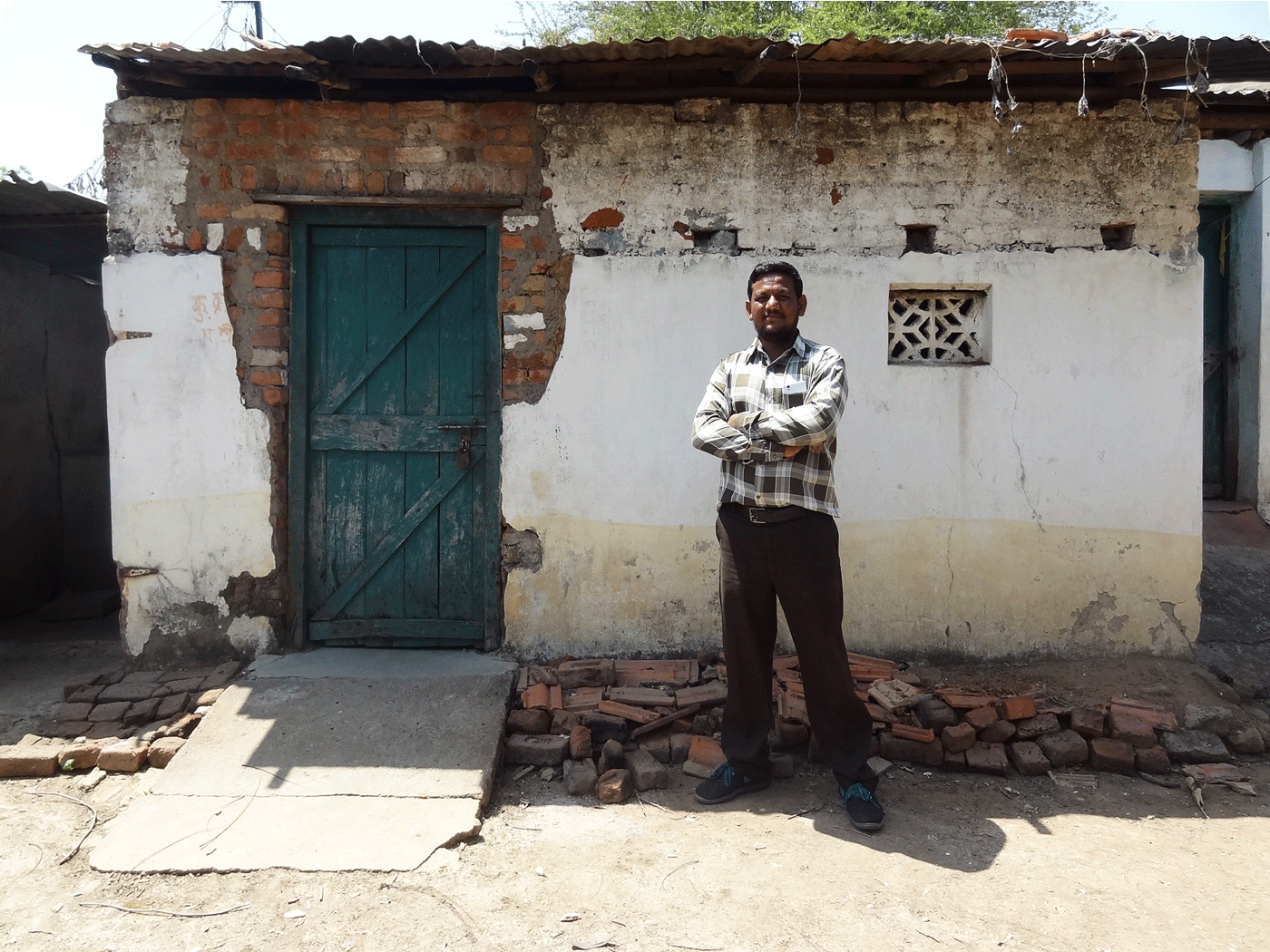

So, the villagers expected their MP, Ahir, would ensure that their demands were met. “But we were shown a rehabilitation site far away, without any amenities. We rejected that site,” says Sachin Chalkhure, a young Dalit activist, walking through the alley that leads to his abandoned house. Chalkhure has been at the forefront of the demand for rehabilitation for his village and other villages in this area impacted by mines of the private as well as public sector.

Many meetings took place. Several protests were organised. But the people were split. Two big landlords sold their land first. Both of them are no more and their families have left the village. “The late Ramkrishna Parkar and late Narayan Kale were the first landowners to sell their land to EMTA,” says Baba Mahakulkar, former sarpanch, resentfully.

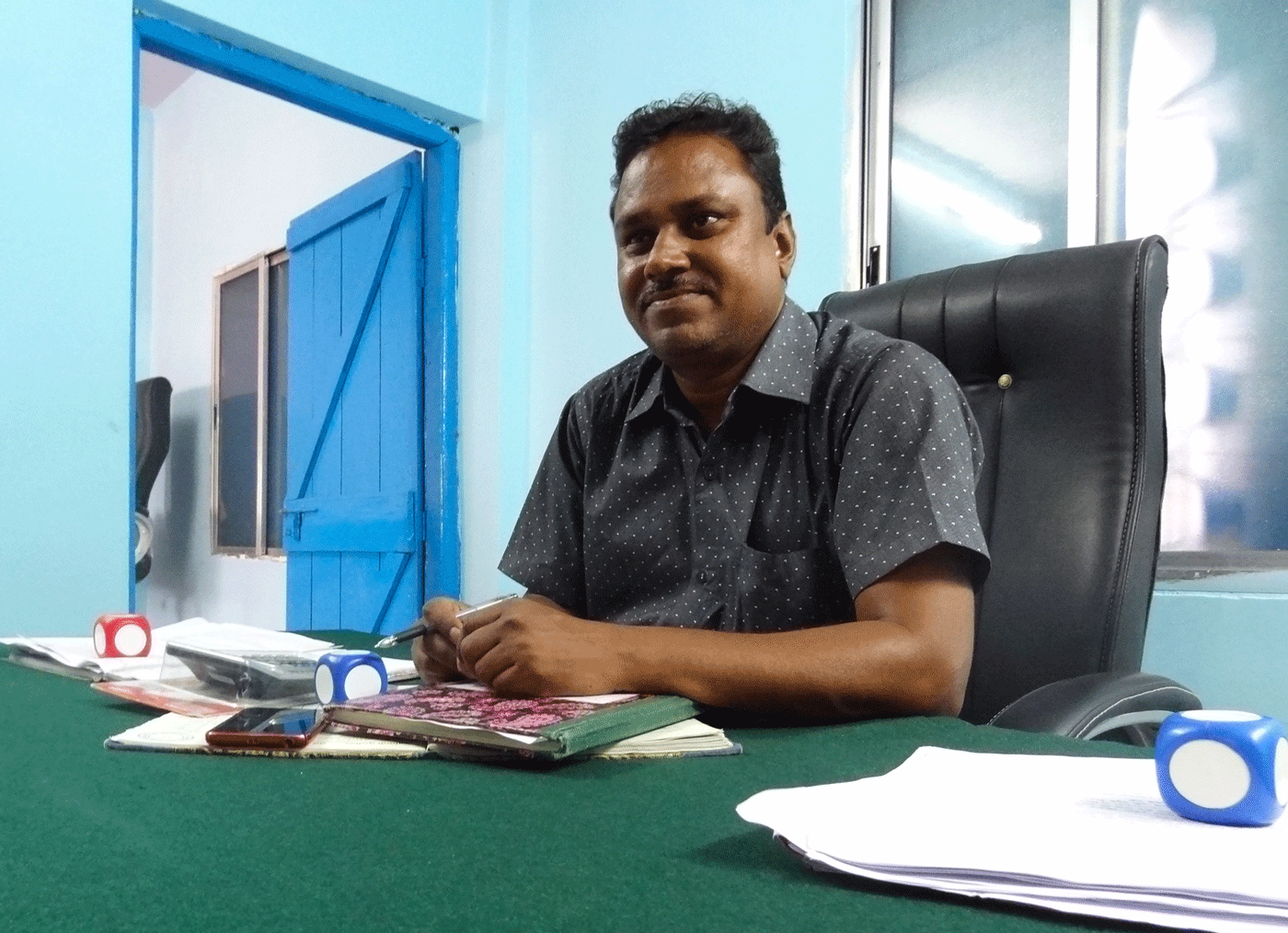

'Every inch here [now] belongs to the company', says Vinod Meshram (left). 'There is a glut of labourers, a dearth of work', says Sachin Chalkhure (right)

“Money got distributed,” adds Chalkhure. “They bribed some of our own to get our land and houses. Relatives and families fought among themselves. The village bled. Besides, some initially gave land voluntarily, thinking they will get jobs in the coal mine.”

Once mining started – first on a small plot, then on expanding stretches – those who had held out were left with no option but to give up their land. “Every single inch here [now] belongs to the company mining the coal,” says Vinod Meshram, the village development officer, sitting in the modest gram panchayat office of Baranj Mokasa. “This office too.”

In the process, the village lost its main occupation – farming. The landless got nothing and lost their main source of work – agricultural labour. “The mine gave jobs to some people, but when it stopped operations the jobs dried up,” says Chalkhure.

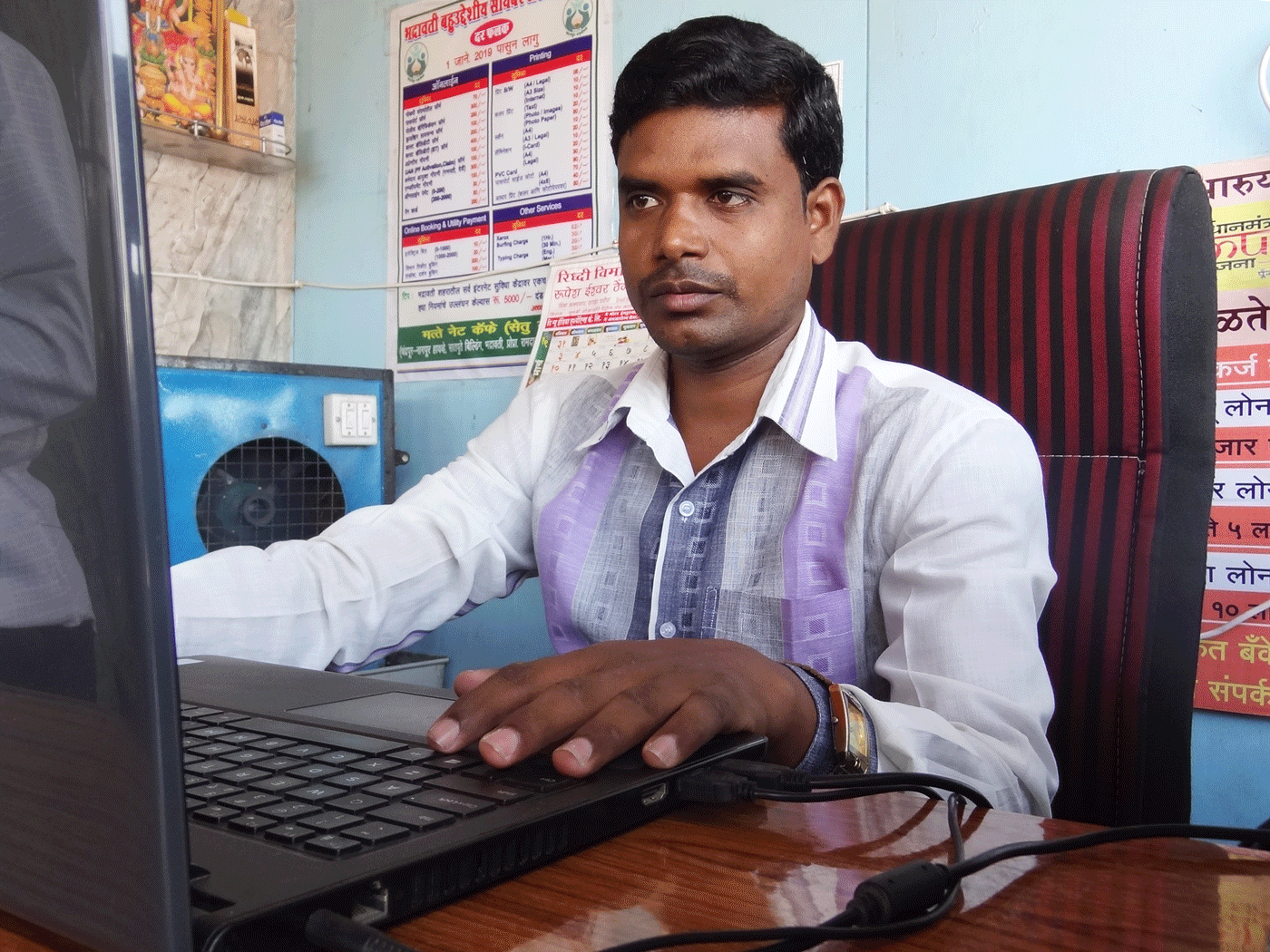

For a while, the mine employed around 450 people, 122 of them from Baranj Mokasa, as clerks, guards or labourers, says Rama Matte, a former clerk at the mine. After losing his job, Matte worked as a mason for three years, and last year set up a ‘Setu’ service centre (a state-approved outlet for government forms, 7/12 extracts and other documents) in Bhadravati town, around four kilometres from the village, on the Nagpur-Chandrapur road. Many others like him who lost their jobs at the mine now work for daily wages or as masons. “Our farms were irrigated, three-cropped land,” Matte recalls.

Many families stayed back amid the pollution and blasts of the mine. Now, four silent mine pits surround the village, machinery lies rusting

The mine remained operational for 4-5 years. In August 2014, the Supreme Court cancelled all the allocations of private captive mines across India while imposing a fine on the coal mined till that date. KPCL later won the bid again, but a court case it filed against EMTA on who will pay the fine, is pending. The Baranj Mokasa mine remains un-operational since the KPCL hasn’t been able to find a new operator. “Our land belongs to the company and the mine is non-operational,” says former sarpanch Mahakulkar. “If and when the court cases are settled and the lease holder re-starts operations, we will have to move out.”.

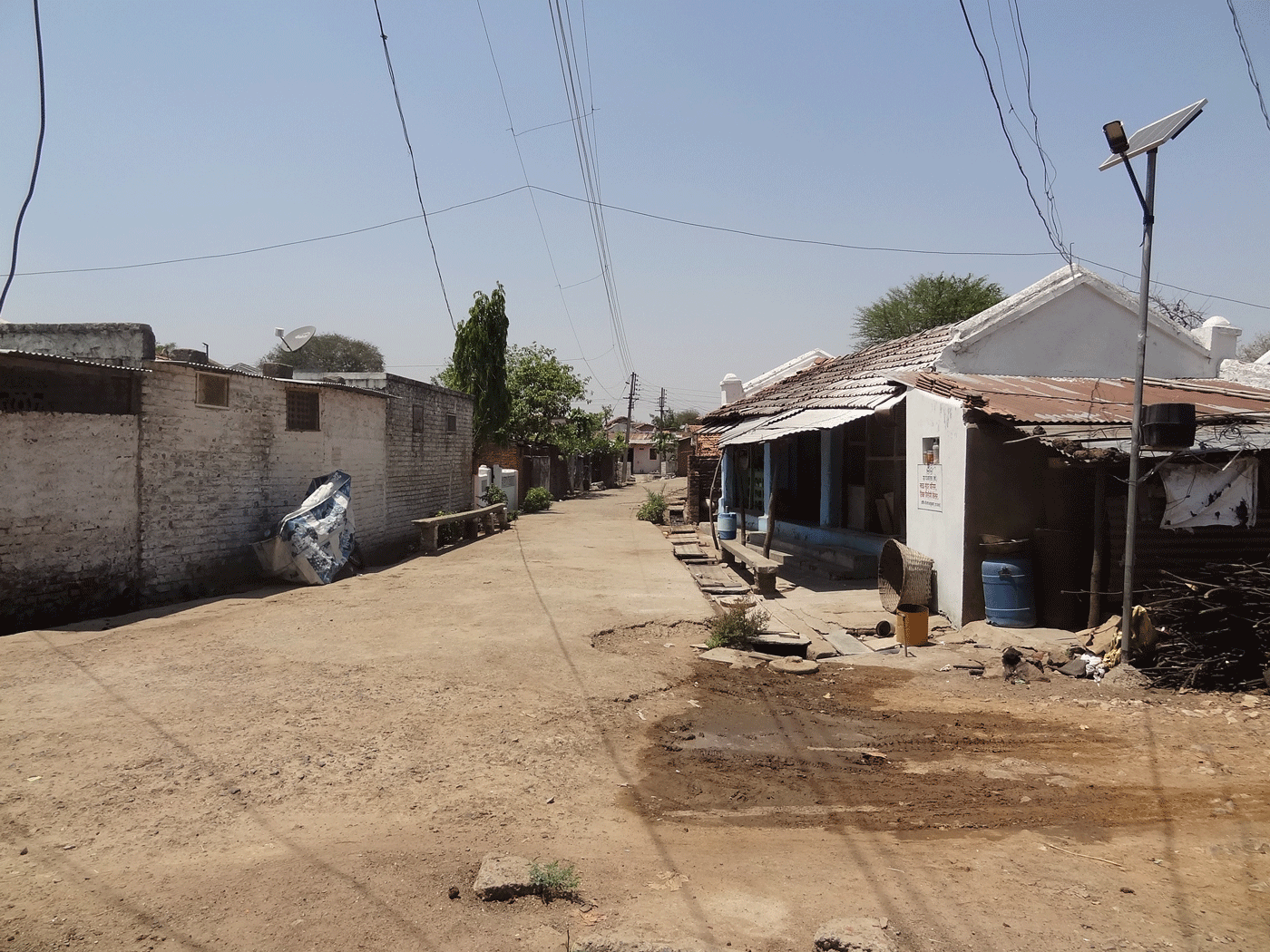

So far, many families have stayed back in the village, despite the noise, pollution, and blasts of the mine when it was operational. The village though has turned into a wasteland of lost work and silent farms. Since it has been acquired, the people can’t get access to any government scheme; homes can’t be improved, roads can’t be re-built.

"We are paying for the mistakes committed by us early on," says Mayatai Mahakulkar, the present sarpanch of this village. "We are nowhere. Old people are having a very tough time.” The landless are the worst affected. They lost their work on farms and they got no compensation or jobs, she adds. Some farmers bought land from the compensation money in faraway villages. "I bought ten acres in a village around 20 kilometres from Baranj, I go there every day…. This is not development."

Four huge mine pits surround the village, an ugly backdrop to the now-barren fields. The oldest pit is full of accumulated rainwater. Machinery is rusting on the hillocks, abandoned by the mining company. “Baranj Mokasa has lost its soul, says Mahadev Kamble, who is in his 80s, sitting in his once-lush mango orchard. “What is left now is a decaying body."

Rama Matte worked as a clerk at the mine, then lost that job

Unemployed youths have left their homes in search of work. Many locked their homes and shifted to Bhadravati town. Among them were Vinod Meshram’s three sons, after the family gave up their 11-acre farmland in 2005. As the village development officer not just for Baranj Mokasa but for a cluster of villages, Meshram continues to get his salary from the state.

Some go to Bhadravati every day for work, which they say is hard to come by. “Many villagers displaced by mines all over this tehsil come to this town for work,” Sachin Chalkhure says. “There is a glut of labourers, a dearth of work.” Sachin too lives in Bhadravati, and works with local NGOs.

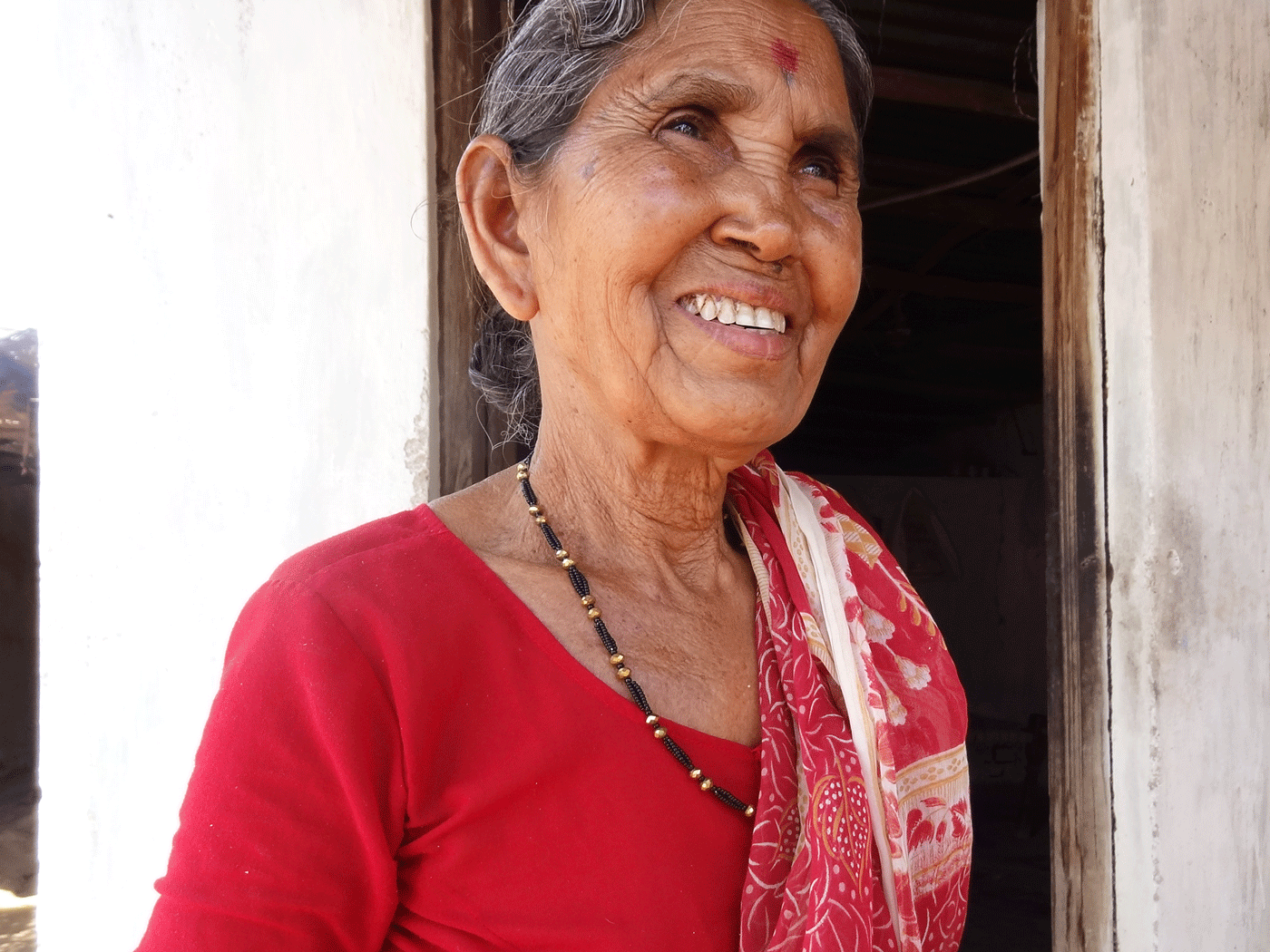

“We did not benefit from this project,” says his grandmother Ahilyabai Patil, who lives in the village all by herself. “Most young men have had to move out for work; we are left behind."

Panchfulabai Velekar’s two sons also had to leave the village. Her family lost two acres to the mine. “We live here. My sons and their families live in Bhadravati,” she says.

Baranj Mokasa’s demand for fair rehabilitation has still not been addressed, despite assurances by the state government. So this time the villagers are saying they will vote against their MP, Hansraj Ahir.

Ahir first won the Lok Sabha election in 1996 and lost the 1998 and 1999 elections to the Congress candidate. Then for three consecutive terms since 2004, Baranj Mokasa has backed Ahir against different Congress candidates.

The Chandrapur Lok Sabha seat has nearly 19 lakh voters spread over six assembly constituency segments, of which four are in Chandrapur district and two in neighbouring Yavatmal district.

'We did not benefit from this project', says Ahilyabai Patil, (left). Panchfulabai Velekar's (right) sons were forced to move to Bhadravati town for work

The Congress has fielded Suresh (Balu) Dhanorkar, a Kunbi by caste and a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) from the Warora (Bhadravati) constituency. Dhanorkar left the Shiv Sena to join the Congress in March 2019. The dominant community in Baranj Mokasa is Kunbi, an OBC; Ahir is a Yadav, also an OBC, but has been a cross-caste consensus candidate.

There is no third major candidate. In three previous elections, a former MLA of the Shetkari Kamgar Paksha, Wamanrao Chatap, made it a three-cornered fight, dividing the votes, which benefitted Ahir.

“There is no way mine-affected [villages] will vote for Ahir again,” says Chalkhure. He and many of his co-activists voted for Ahir in previous Lok Sabha elections, hoping that he would fight for higher compensation and better rehabilitation. “We feel we have been cheated,” he adds. “That anger will come out in the elections in these villages.”

Sitting under the lone tree in his orchard, Kamble too reiterates: “We aren’t voting for Ahir, come what may; he has dumped us.” In the forlorn village, this seems to be the resolve: ‘Dump the leader who has dumped us’.