Bantu Durga Rao’s coconut plantation in Kotapalem village in coastal Andhra Pradesh could soon disappear. His one acre is part of the 2,073 acres in three villages – Kotapalem, Kovvada, Maruvada (and its two hamlets, Gudem and Tekkali) – in Srikakulam district that are being acquired by the district administration for a Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL) plant.

But in May 2017, Durga Rao got a loan of Rs. 60,000 from the Andhra Pradesh Grameen Vikas Bank. “On the one hand, the banks are giving agricultural loans and on the other, the revenue authorities claim that survey number 33 [where his land is located] is a stream of water. Both are government agencies. How can both be true?” he asks, puzzled.

The power plant is likely to displace around 2,200 families of farmers and fisherfolk, says a January 2017 Social Impact Assessment report done by the Environment Protection Training and Research Institute, Hyderabad. Most of them are from Dalit and OBC communities. The report estimates the project will cost Rs. 4 lakh crores.

The process of acquiring land in the three villages and two hamlets of Ranastalam block began in 2011, and accelerated after the 2014 general elections. But in March 2018, the state’s ruling Telugu Desam Party quit the National Democratic Alliance government, and since NPCIL is a central government agency, “the project will only further get delayed,” says Sunkara Dhanunjaya Rao, the sarpanch of Kotapalem.

This has added to the uncertainty and confusion among the villagers.

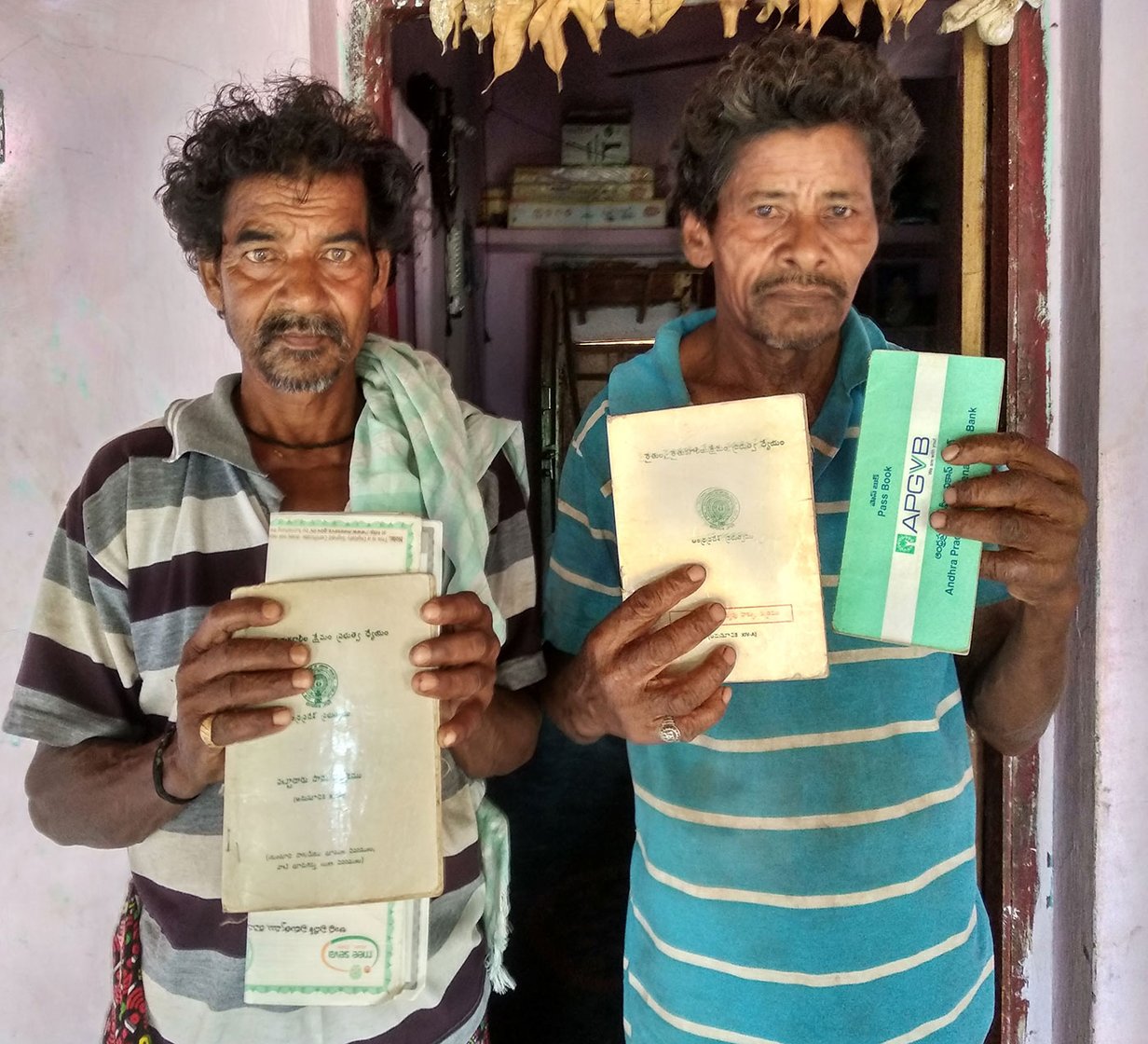

Left: Myalapilli Kannamba (here with her son), wonders how many years it will take to rebuild even their thatched houses if they are displaced. Right: Durga Rao and Yagati Asrayya will each lose their one acre, and wonder how banks (whose passbooks they show me) are still giving them loans on it

“Of the Rs. 225 crores required [as cash compensation for acquiring the 2073 acres across the three villages], the government has sanctioned only Rs. 89 crores till now,” Dhanunjaya Rao says. And, villagers complain, the amounts they are being given are far less than the market value of the land.

“I was paid 15 lakhs per acre when we demanded 34 lakhs, on a par with the compensation given for land acquisition for the Bhogapuram airport, 35 kilometres away. And the market value of the land is close to Rs. 3 crores [per acre], due to the proximity of the Chennai-Kolkata national highway,” insists Badi Krishna, 58, who owns three acres of revenue land in Kovvada (listed as Jeerukovvada in the Census) on which he grows coconut, banana and chickoo.

According to the Land Acquisition Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR), compensation should be calculated on the basis of the average value of land transactions in the last one year in the region. However, the legal procedure was not followed and the district administration declared a compensation amount of Rs. 18 lakhs. Even that full amount is yet to be given to those who have received some money – and only 20 to 30 per cent of the 2,073 acres have been compensated for so far, estimate local activists.

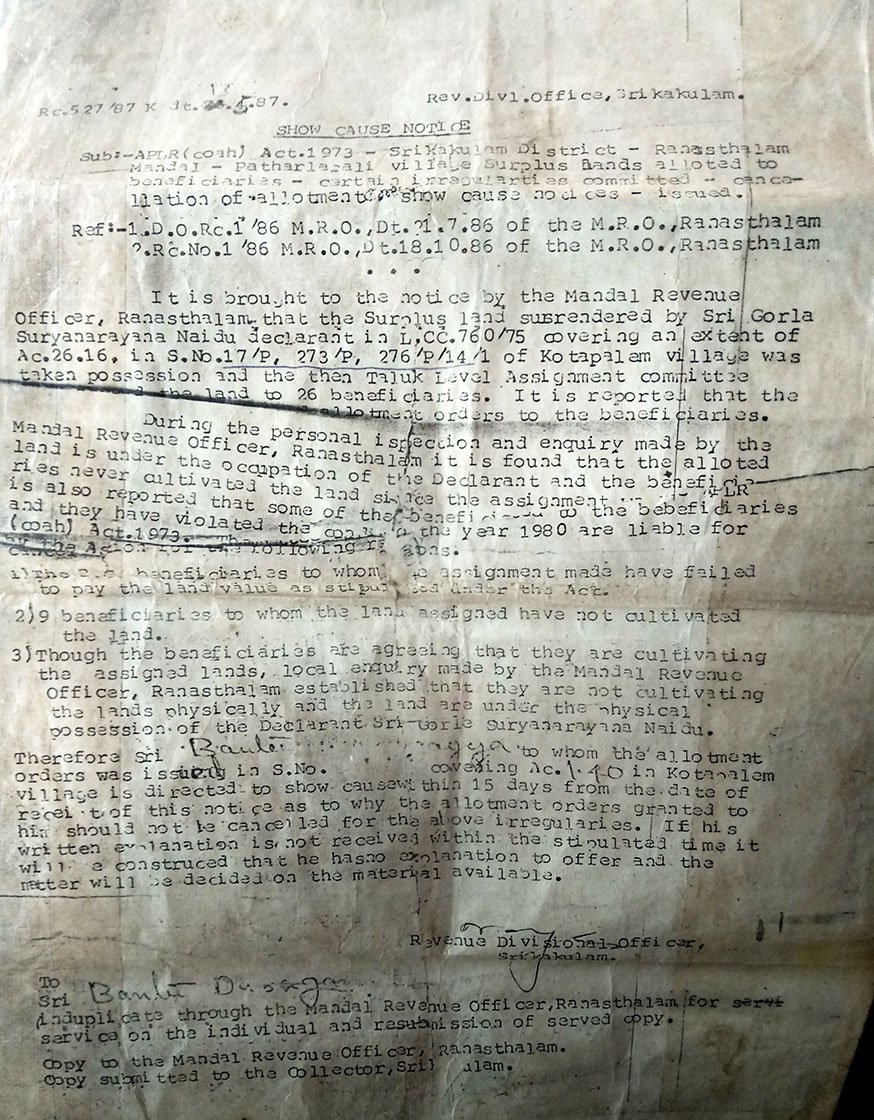

A notice from the Revenue Divisional Officer saying that Durga Rao was allotted the land in 1973

The 2,073 acres includes 18 acres that belong to 18 Dalit families in Kotapalem, including Durga Rao’s. Each family got an acre under the Andhra Pradesh Land Reforms (Ceilings on Agricultural Holdings) Act, 1973. They were given D-form pattas , which meant that any transaction of the land is illegal – the land can only be inherited within the family.

“When we got the land, we didn’t have the capital to invest in cultivation. There was no irrigation facility and the only water was rain. We didn’t have the money to invest in borewells either. So we gave the land on lease to [upper caste] Kapu and Kamma farmers, who dug borewells and cultivated the land till 2011,” says Yagati Asrayya, 55, of Kotapalem, who too owns one acre on this stretch. In those decades, he and the other small land-holders in these villages worked as agricultural labourers.

When news of the proposed power plant started trickling in, fearing loss of their land, many of the land-owners took over the cultivation themselves. But, they allege, in several instances, the revenue department is giving the compensations to the upper caste farmers, “while telling us that we can’t get compensation because our lands are part of a stream,” says Donga Appa Rao, 35, who owns an acre adjacent to Durga Rao’s plot.

Even other provisions under the LARR law, like a one-time R&R settlement

package of Rs. 6.8 lakhs per family, and valuation of and compensation for

houses, boats, nets, trees and livestock, have not been processed. Myalapilli Kannamba,

56, a resident of Kovvada asks, “We might be having only thatched houses, but

we have five of them. We are getting old day by day – how many years will it

take to rebuild all of them?”

The Kovvada nuclear power plant, which will have a capacity of 7,248 MW (megawatts) is the first one being set up under the India-US Civil Nuclear Agreement of 2008. Its original site was Mithivirdi village in Talaja taluka of Gujarat's Bhavnagar district. But farmers there protested for years and ensured it was shifted – the proposed plant has now come to Kovvada.

The Integrated Energy Policy , 2006, of the government of India states that the country will have installed nuclear power capacity of 63,000 MW by 2032 – at present, it reportedly has a total installed capacity of 6,780 MW in seven nuclear power plants. Of the proposed increase, as much as 30,000 MW will be installed on the coast of Andhra Pradesh at around four different locations. At present, only the Kovvada project is inching ahead, while land acquisition for a plant near Kavali city in Nellore district is underway.

Left: In December 2016 government officials conducted a public hearing where the villagers protested strongly. Right: Around 2,000 families across five villages will lose their land, crops, and coconut and banana plantations such as these in Kotapalem

This at a time when, according to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report , 2017, across many parts of the world, the number of under-construction reactors is decreasing. Russia, USA, Sweden and South Korea have closed down reactors in the last four years, the report says.

Besides, the International Renewable Energy Agency , located in Abu Dhabi, notes that the prices of renewable energy have been falling since the last few years. If Andhra Pradesh needs more power, it could invest in renewable forms rather than nuclear and thermal energy.

Going against these trends, India’s energy policy claims that nuclear power is being promoted to meet the growing energy needs of the country. However, Ajay Jain, principal secretary of the Energy, Infrastructure and Investment Department, government of Andhra Pradesh, speaking to The Hindu in April 2017, said that Andhra Pradesh has a power surplus, with a generation capacity of 200 MU (million units) per day, against an average daily demand of 178 MU. “Why do you need to install so many nuclear reactors in a state that is already power surplus?” asked Dr. E.A.S. Sarma, former union secretary, Department of Energy, Ministry of Power, when this reporter spoke to him.

However, G.V. Ramesh, former project director of the Kovvada Nuclear Power Plant and ex-chief engineer of NPCIL, tells me, “We will spend Rs. 24 crores per MW of nuclear power generated and we will supply the electricity to people at a subsidised cost of Rs. 6 KWh (kilowatt-hour).”

Fishermen in Kovadda hope the move will at least make fishing sustainable again, unaware that the nuclear power waste could further destroy the water

But

studies by scientists argue otherwise. Dr. K. Babu Rao, former deputy director

of the Indian Institute of Chemical Technology in Hyderabad, says, “Earlier,

NPCIL said that they will provide nuclear energy at Re. 1 /KWh and have now

increased it to Rs. 6. They are speaking plain lies. The first year tariffs

will range from Rs. 19.80 to Rs. 32.77 per KWh.” Dr. Rao quotes the numbers

from a March 2016 study by the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial

Analysis in Cleveland, USA.

Besides, the Atomic Energy Regulation Board (AERB) has not yet given site clearance in Kovadda for the nuclear plant, notes Narsinga Rao, state secretariat member of the Communist Party of India (M). “And the project authorities are yet to apply for clearance from the Ministry of Environment and the AP Pollution Control Board. General Electric, which was supposed to execute the deal as per an agreement signed in 2009, backed out. Now, Westinghouse Electric Company is bankrupt and having second thoughts about the viability of the project,” he adds. “If AERB and WEC are not yet prepared for the project, why are the Prime Minister’s Office and the government of Andhra Pradesh bent on acquiring land?”

While the land acquisition continues, a township is being constructed on 200 acres in Dharmavaram village of Etcherla mandal , around 30 kilometres north of Kovvada. When construction of the power plant starts and families are displaced from the five villages, the plan is to house them all here.

Myalapilli Ramu, 42, a fisherman from Kovadda awaiting displacement, is hoping the move will at least make fishing sustainable again. (See Big Phrama kills small fish in Kovvada ) “We can no longer fish here [on the coast of Kovadda] due to the water pollution by pharmaceutical industries. Since Dharmavaram is close to the coast too, we hope to do some fishing once we go there,” he says. Little does he know that the water pollution caused by a nuclear power plant could be of a much higher magnitude in the entire region than pharmaceutical pollution.

Some of the villagers are now planning to file a case in the Andhra Pradesh High Court in Hyderabad to fight for fair and lawful compensation if they are displaced by the nuclear power plant.