“We were sitting in the tent, they tore it down. We kept sitting,” the old freedom fighter told us. “They threw water on the ground and at us. They tried making the ground wet and difficult to sit on. We remained seated. Then when I went to drink some water and bent down near the tap, they smashed me on the head, fracturing my skull. I had to be rushed to hospital.”

Baji Mohammed is one of India’s last living freedom fighters – just one of four or five nationally recognised ones still alive in Odisha’s Koraput region. He is not talking about British brutality in 1942. (Though he has much to say on that, too.) He’s describing the vicious attack on him during the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, half a century later: “I was there as part of a 100-member peace team.” But the team was given no peace. The old Gandhian fighter, already in his mid-seventies, spent 10 days in hospital and a month in a Varanasi ashram recovering from the injury to his head.

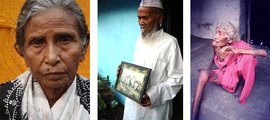

There is not an iota of anger as he describes the event. No hatred towards the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or Bajrang Dal that led the attack. Just a gentle old man with a charming smile. And a firm Gandhi bhakt . He’s a Muslim who heads the anti-cow slaughter league of Nabrangpur. “After the attack, Biju Patnaik came to my home and scolded me. He was worried about my being active even in peaceful protest at my age. Earlier, too, when I did not accept this freedom fighter’s pension for 12 years, he chided me.”

Baji Mohammed is a colourful remnant of a vanishing tribe. Countless rural Indians sacrificed much for India’s freedom. But the generation that led the nation to it is dying out swiftly, most of its members in their late 80s or 90s. Baji is closing in on 90.

“I was studying in the 1930s, but did not make it past matric. My guru was Sadashiv Tripathi who later became Odisha chief minister. I joined the Congress party and became president of its Nabrangpur unit [then still a part of Koraput district]. I made 20,000 members for the Congress. This was a region of great ferment. And it came fully alive with satyagraha .”

However, while hundreds marched towards Koraput, Baji Mohammed headed elsewhere. “I went to Gandhiji. I had to see him.” And so he “took a cycle, my friend Lakshman Sahu, no money, and went from here to Raipur.” A distance of 350 kilometres of very tough, mountainous terrain. “From there we took a train to Wardha and went on to Sewagram. Many great people were at his ashram. We were awed and worried. When could we meet him, if ever? Ask his secretary Mahadev Desai, people told us.

“Desai told us to talk to him during his 5 p.m. evening walk. That’s nice, I thought. A leisurely meeting. But the man walked so fast! My run was his walk. Finally, I could no longer keep up and appealed to him: Please stop: I have come all the way from Odisha just to see you.

“He said testily: ‘what will you see? I too, am a human being, two hands, two legs, a pair of eyes. Are you a satyagrahi back in Odisha?’ I replied that I had pledged to be one.

“'Go', said Gandhi. ‘ Jao, lathi khao [Go and taste the British lathis ]. Sacrifice for the nation.’ Seven days later, we returned here to do exactly as he ordered us.” Baji Mohammed offered satyagraha in an anti-war protest outside the Nabrangpur Masjid. It led to “six months in jail and a Rs. 50 fine. Not a small amount those days.”

More episodes followed. “On one occasion, at the jail, people gathered to attack the police. I stepped in and stopped it. ‘ Marenge lekin maarenge nahin' , I said [We shall die, but we shall not attack].”

“Coming out of jail, I wrote to Gandhi: 'what now?' And his reply came: ‘Go to jail again'. So I did. This time for four months. But the third time, they did not arrest us. So I asked Gandhi yet again: 'now what?' And he said: ‘Take the same slogans and move amongst the people'. So we went 60 kilometres on foot each time with 20-30 people to clusters of villages. Then came the Quit India movement, and things changed.

“On August 25, 1942, we were all arrested and held. Nineteen people died on the spot in police firing at Paparandi in Nabrangpur. Many died thereafter from their wounds. Over 300 were injured. More than 1,000 were jailed in Koraput district. Several were shot or executed. There were over 100 shaheed (martyrs) in Koraput. Veer Lakhan Nayak [legendary tribal leader who defied the British] was hanged.”

Baji’s shoulder was shattered in the violence unleashed against the protesters. “I then spent five years in Koraput jail. There I saw Lakhan Nayak before he was shifted to Berhampore jail. He was in the cell in front of me and I was with him when the hanging order came. What should I tell your family, I asked him. ‘Tell them I am not worried,’ he replied. ‘Only sad that I will not live to see the swaraj we fought for.’”

Baji himself did. He was released just before Independence Day – “to walk into a newly-free nation.” Many of his colleagues, amongst them future Chief Minister Sadashiv Tripathi, “all became MLAs in the 1952 elections, the first in free India.” Baji himself “never contested the polls. Never married.

“I did not seek power or position,” he explains. “I knew I could serve in other ways. The way Gandhi wanted us to.” He was a staunch Congressman for decades. “But now I belong to no party,” he says. “I am non-party.”

It did not stop him from being active in every cause which he thought mattered to the masses. Right from the time “I took part in the bhoodan movement of Vinoba Bhave in 1956.” He was also supportive of some of Jayaprakash Narayan’s campaigns. “He stayed here twice in the 1950s.” The Congress asked him to contest elections more than once. “But me, I was more seva dal than satta dal [More service oriented than power seeking]."

For freedom fighter Baji Mohammed, meeting Gandhi was “the greatest reward of my struggle. What more could one ask for?” His eyes mist over as he shows us pictures of himself in one of the Mahatma’s famous protest marches. These are his treasures, having gifted away his 14 acres of land during the bhoodan movement. His favourite moments during the freedom struggle? “Every one of them. But of course, meeting the Mahatma, hearing his voice. That was the greatest moment of my life. The only regret is that his vision of what we should be as a nation, that is still not realised.”

Just a gentle old man with a charming smile. And a sacrifice that sits lightly on aging shoulders.

Photos: P. Sainath

This article was originally published in

The Hindu

on August 23, 2007.

More in

this series

here:

Panimara's foot soldiers of freedom - 1

Panimara's foot soldiers of freedom - 2

The last battle of Laxmi Panda

Sherpur: big sacrifice, short memory

Godavari: and the police still await an attack

Sonakhan: when Veer Narayan Singh died twice