“Didi, please do something or they will kill me anytime soon!” Those were Girija Devi’s first words when I met her. “I have locked myself up in this tiny, dark room since yesterday afternoon so that they don’t hit me,” she sobbed.

Walking through a narrow passage of the house where piled up utensils waited to be washed, I had reached the room where Girija had shut herself away from her in-laws. Outside the room was a kitchen and a small, open area where her husband and children eat their meals.

Girija, 30, married Hemchandra Ahirwar, 34, a mason, 15 years ago. They have three children aged 14, 11 and 6.

The problem began when her in-laws found Girija arguing with them over every unfair demand they would make of her – including that she quit her job. It has grown worse after she took up that job – as an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) in her own village – Basaora in Kabrai block of Uttar Pradesh’s Mahoba district. And now, with her in-laws back in the village during the lockdown, it has become unbearable.

“Things were under control before the lockdown, with both of them [her father-in-law and mother-in-law] in Delhi,” says Girija. They worked there as labourers. “But ever since they’re back, it has become difficult for me to survive. Earlier they would say that I was going to meet with other men whenever I would go to see any pregnant woman in the village or take them to the hospital. Being an ASHA, this is my duty.” Her six-year-old son, Yogesh, followed us as we walked upstairs to the terrace.

Girija has been crying a lot, her eyes and lips appear swollen. She and Hemchandra live in a joint family. Two of his uncles and their families share the same house, though with separate kitchens and portions. However, the entrance and courtyard remain common.

Girija Devi with her six-year-old son Yogesh: 'It has become difficult for me to survive'

The violence Girija is enduring has echoed, on a rise, in many households over the last few months. “There has been an increase in domestic violence cases after the lockdown,” says Rekha Sharma, chairperson, National Commission for Women, over the phone. “The majority of complaints come either online through our website, or on our WhatsApp number – though the 181 helpline is also available. But most times, it’s not easy for the victim to talk over the phone.”

And these complaints don’t reflect the real extent of the increase. “We believe domestic violence is one category of crime which always was underreported,” says Aseem Arun, additional director general of police (ADGP), Uttar Pradesh. He oversees, among other duties, the UP police helpline – 112. But now, since the lockdown began, he says, “The chances of the violence being underreported are much higher.”

This is a worldwide gap, not one that is restricted to India – of the difference between actual and reported instances of violence. As UN WOMEN notes : “Wide under-reporting of domestic and other forms of violence has previously made response and data gathering a challenge, with less than 40 per cent of women who experience violence seeking help of any sort or reporting the crime. Less than 10 per cent of those women seeking help go to the police. The current circumstances [the pandemic and lockdowns] make reporting even harder, including limitations on women’s and girls’ access to phones and helplines and disrupted public services like police, justice and social services.”

“Yesterday my husband’s grandfather hit me with a lathi [stick] and even tried to throttle me” says Girija, fighting her tears, “but a neighbour stopped him. He then abused that man too. Now when I try to discuss my problem with any of my neighbours, they say go home and sort it out, because they don’t want to hear abuses from my in-laws. Things would have been better if my husband would speak for me. But he says that we must not oppose our elders. He’s afraid that they’d beat him up too, if he does.”

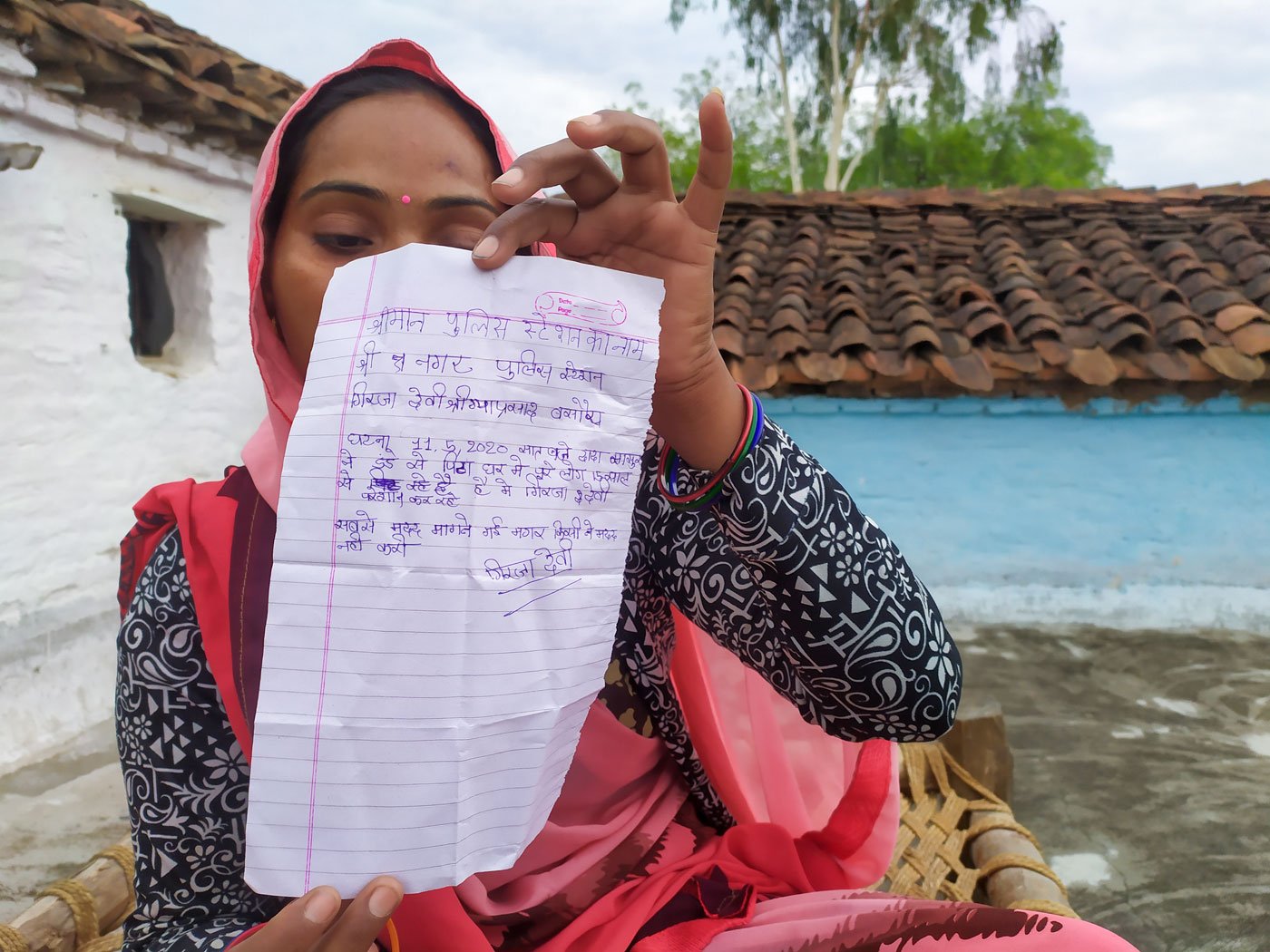

Girija with the letter of complaint for the police that she had her 14-year-old daughter Anuradha write on her behalf

Many women have faced such violence. According to the National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-16), over one third of women said they had experienced domestic violence – but just about 1 in 7 of them had sought help from any one (including the police) to stop the violence.

But what sparked the present crisis in Girija’s household?

“As soon as they [her in-laws and husband’s grandparents] arrived from Delhi after the first few weeks of the lockdown, I asked them to get screened for the virus and get a check-up done, for there are children in the house. But they abused me saying I was defaming them and alleging they were Covid-19 patients. My mother-in-law tried to slap me. There were 8 to 10 people watching all this happen outside my house. Nobody came forward to help me,” says Girija. Even as we talked, she looked around warily to ensure that nobody was watching.

That indifference and even complicity by silence is also a worldwide phenomenon, as a 2012 report, In Pursuit of Justice , pointed out. It showed that in 17 out of 41 countries, a quarter or more people think it justifiable for a man to beat his wife. In India, it found, that figure was 40 per cent.

Girija then shows me a letter of complaint she had her 14-year-old daughter Anuradha wrote on her behalf. “We wanted to give it to the police,” Anuradha told me, “but because of the lockdown, we are not allowed into Mahoba town. They stopped us at the barrier.” The town is around 25 kilometres from her village. Girija then spoke to the Superintendent of Police, Mahoba, on the phone as she was not allowed to move outside the village. He assured her of action. [Our meeting and conversation was possible because this reporter arrived at Girija’s home with the Station House Officer and a constable of Mahoba town police thana ].

Mani Lal Patidar, the SP at Mahoba, said, “We usually do not arrest the accused in domestic violence cases on the first, or second, complaint filed against them. Initially, we counsel them. In fact, we do the counselling of both accused and victim once, twice, or even thrice. Only when we find the situation is not getting any better, do we file the FIR.”

'There has been an increase in domestic violence cases after the lockdown', says Rekha Sharma, chairperson, National Commission for Women

With the lockdown, adds ADGP Arun, “We noticed a steep drop in the number of domestic violence events [complaints] we received. It came down to almost 20 per cent of what they used to be and stayed so for a week, 10 days, but then there was a steady increase. At a point of time when I suspect the liquor shops (re)opened, there was again a spurt, presuming a link between liquor and domestic violence. But now there’s a 20 per cent drop again in cases [compared to pre-lockdown numbers].”

Is that because domestic violence is underreported? “That is true,” says ADGP Arun. It was always so, “but now, since the perpetrator is right in front of the lady, chances of underreporting are still higher.”

Instead, more women are probably turning to other helplines and groups. “The domestic violence cases we are getting now are thrice what they were before the lockdown. Most complaints come online and on the phone. What’s shocking is that we got complaints even from a medical doctor, an MBBS,” says Renu Singh, senior lawyer and executive director, Association of Advocacy and Legal Initiatives, Lucknow.

Like Girija, Priya Singh – from Chinhat block headquarters in Lucknow district – is also locked down with violence in her own house.

Priya, 27, married Kumar Mahendra, 42, when she was 23 and has a 4-year-old son. “Earlier he would come drunk from work, but these days he drinks even in the afternoon. The beatings are constant now. My child also understands this and is always scared of him,” she says.

''The beatings are constant now', says Priya Singh

“Normally people reach out to us to complain if they or their known ones face domestic violence. But since there’s no movement now [due to the lockdown], they can’t come to us anymore. So we came up with helpline numbers. And now we receive 4-5 calls a day on average. All of them are about domestic violence from various districts of Uttar Pradesh,” says Madhu Garg, vice president, UP, of the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA).

Priya’s husband worked as a helper at a chikankari garments showroom in Lucknow. But the shop shut down with the lockdown and he now stays at home. Priya intends to file a complaint against him when she can get to her parents’ place in Kanpur.

“Nobody would believe that he has sold many utensils from our house just to get some money to buy alcohol,” says Priya. “He even tried selling rations I got from the ration shop, but my neighbours warned me and I somehow stopped him. He beat me up in front of everyone. Nobody cared to stop him,” she said.

In Uttar Pradesh, according to NFHS-4, with 90 percent of married women in the age group 15-49 who experienced physical violence – the perpetrators were their husbands.

Girija’s parents live in Delhi with her still unmarried younger sister. “I can’t even think of going to them. They barely survive in a small

jhuggi

there. How can I add one more stomach for them to feed? Maybe this is what my destiny is,” says Girija.

“Of all women in India who have ever experienced any type of physical or sexual violence,” says NFHS-4, “76 percent have never sought help nor told anyone about the violence they experienced.”

Nageena Khan's bangles broke and pierced the skin recently when her husband hit her. Left: With her younger son

In Kalwara Khurd village of Chitrakoot’s Pahari block, Nageena Khan, 28, wants to escape to her parents in Prayagraj, about 150 kilometres away.

"My entire body is full of scars. Come and see for yourself," she says, pulling me inside her house. "The way my husband beats me every second day, I am not in a condition to walk by myself. Why do I live here? When I am being hit and unable to walk a step? There is no one to give me a sip of water when I can't move.

“Do me a favour,” she adds. “Please drop me at my parents’ house.” Her parents have agreed to come and take her home – but can only do that when public transport resumes. Nageena intends to file a complaint against her husband Sareef Khan, 37, a freelance driver, when she gets away from this home.

The March 25 national lockdown was an emergency public health measure to halt the spread of Covid-19. But being locked down with abusers creates a health emergency of another kind for women like Girija, Priya and Nageena.

“There are many women in this village who are often beaten by their husbands but have accepted living like this,” Girija Devi told me in Basaora. “I speak against it, so I get into trouble. But you tell me, why should I let anyone disrespect me only because I am a woman and I step out of my house to work? I will keep speaking against it till my last breath.”