As we got down from the jeep, constables moved in panic towards their positions in the fortified Rajavommangi police station. The station itself is under police protection. Special armed police are all around it. That we were armed with just a camera did little to reduce the tension. Photographing police stations in this part of East Godavari is banned.

From the security of the inner corridor, the head constable wanted to know who we were. Journalists? Things relaxed a bit. “Aren’t you reacting a bit late?” I asked. “The attack on your station occurred 75 years ago.”

"Who knows?" he said philosophically. “It could happen again this afternoon.”

These tribal tracts of Andhra Pradesh are known as the ‘Agency’ area. They rose in revolt in August 1922. What at first seemed to be an outburst of local anger soon gained wider political meaning. A non-Adivasi, Alluri Ramachandra Raju (better known as Sitarama Raju), led the hill tribes in the Manyam uprising, as it is locally known. Here, people were not just seeking grievance redressal. By 1922, they were fighting to eject the Raj itself. The rebels announced their aims with attacks on several police stations in the Agency area, including the one at Rajavommangi.

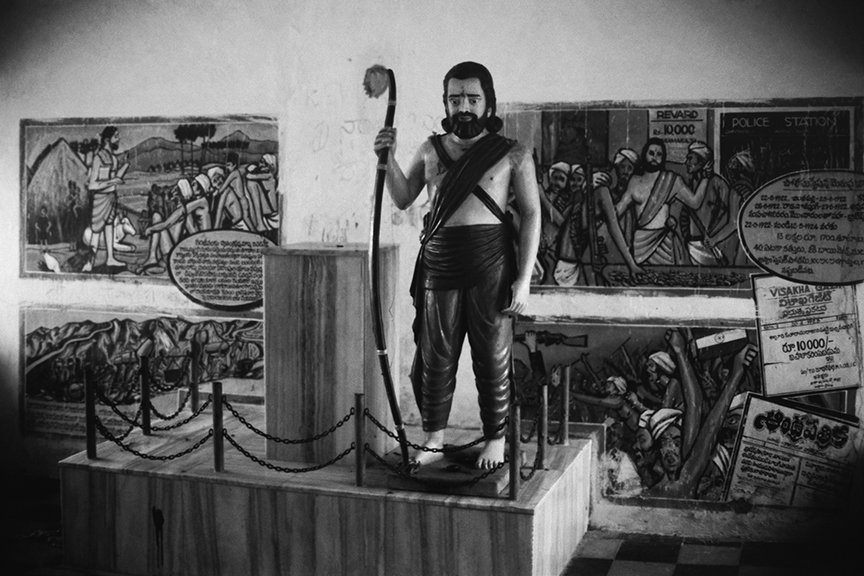

Sitarama Raju’s statue in East Godavari

Many problems of this region that fought the British are as alive today as 75 years ago.

Raju’s ragged irregulars bogged down the British in a full-scale guerrilla war. Unable to cope, the British brought in the Malabar Special Force to crush the revolt. They were trained in jungle warfare and equipped with pack wireless sets. The rebellion ended in 1924 with Raju’s death. Yet, for the British, as historian M. Venkatarangaiya wrote: “It caused much more of a headache than the non-cooperation movement.”

This year marks the birth centenary of Sitarama Raju who was all of 27 years old when killed.

Colonial rule devastated the hill tribes. Between 1870 and 1900, the Raj declared many forests as “reserves” and banned podu (shifting) cultivation. Soon it curbed the right of the Adivasis to collect minor forest produce. The forest department and its contractors took over that right. Next, they extracted forced, and often unpaid, labour from the tribals. The area fell in the grip of non-Adivasis. Often, punishments included seizure of land. With these moves, the region’s subsistence economy fell apart.

Sitarama Raju's samadhi in Krishnadevipet

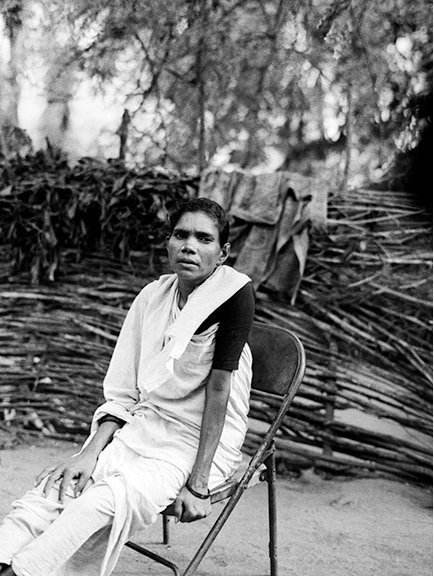

“The landless suffer badly today,” says Ramayamma, a Koya tribal of Rampa. “I don’t know about 50 years ago.”

Rampa was a staging point for Raju. In this small village of around 150 households, nearly 60, including Ramayamma’s, are landless.

It wasn’t always so. “Our parents lost land after taking loans of around Rs. 10,” she says. Also, “outsiders posing as tribals come and take over our land.” The biggest landowner here was a man from the plains who worked in the records office. This gave him access to title deeds in the area. And people believe he tampered with those. His family now hires nearly 30 workers daily in season. Unusual, in a village where most landholdings are around three acres or less.

The land issue is exploding in West Godavari district. And simmering in the East. Much Adivasi land, says a tribal development agency officer, “was lost after Independence when their rights should have been protected.” Some 30 per cent of land in the region was alienated between 1959 and 1970. Oddly, “the passage of the Andhra Pradesh State Land Transfer Regulation Act of 1959 did not halt the trend.” The Act, better known as Regulation 1/70, was meant to stop precisely this. Now there are moves to further dilute the Act itself.

In another landless household of Rampa, P. Krishnamma speaks of her family's present-day struggles

The tribal versus non-tribal standoff is complex. There are also non-Adivasi poor here. So far, despite the tensions, they are not targets of Adivasi anger. That goes back some way in history. Raju’s rules during the revolt held that only the British and government institutions were to be attacked. The rebels of Rampa saw their war as being against the British.

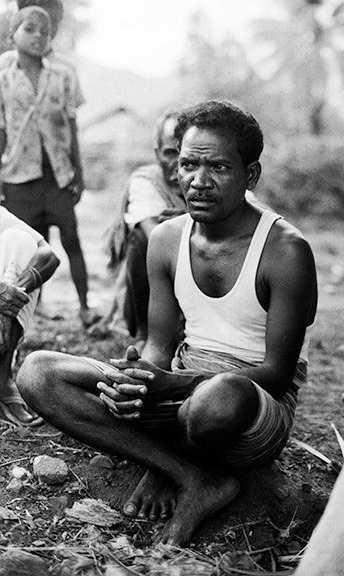

Today, the better-off among the non-Adivasis exploit both the tribals and their own poor. And the lower bureaucracy here is mainly non-tribal. There are ways around Regulation 1/70. “Leasing is rampant here,” says landless Koya tribal Pottav Kamraj in Kondapalli village. Leased land seldom returns to the owner. Some outsiders even take an Adivasi woman as a second wife to gain tribal land. Kondapalli fell in Sitarama Raju’s action zone. From here, the British sent rebels to the Andamans, smashing the clans and pauperising the village.

That cracking up of communities means that direct popular memory of the period is fractured. But Raju’s name still spells magic. And the issues remain. “Minor forest produce is not a great problem,” jokes Kamraju Somulu in Mampa village of Vizag district. “There is very little forest left.” Which means more hardship in places where the poor, says Ramayamma, “often have just kanji water for a meal.” That East Godavari is one of India’s richer rural districts has not helped.

Classes are also emerging within the Adivasis. “The rich Koyas lease their land to outsider Naidus, not to us within the village,” says Pottav Kamraj in Kondapalli. “The rich always get together.” Few tribals find government jobs. And landless labourers in these parts can’t find work for several months in the year.

The poor "often just have kanji water for a meal," says Ramayamma, a landless Koya tribal of Rampa (L), “The rich always get together,” says landless Koya tribal Pottav Kamraj in Kondapalli village (R)

Wage struggles have broken out in the West and could move to East Godavari, too. Besides, rich non-tribals are co-opting some tribal chiefs. In Mampa, the panchayat president, an Adivasi, is now a big landowner. His family holds around 100 acres. “He is fully with the outsiders,” says Somulu.

The Raj failed to co-opt Alluri Sitarama Raju in his lifetime. Giving him 50 acres of fertile land did not work. The British could not fathom why a man with no personal grouse was inseparable from the tribals. One British report even suggested he was “a member of some Calcutta secret society.” Apart from the Raj, quite a few plains leaders, including top Congressmen, opposed him. Several in 1922-24 called for suppressing his revolt. In the Madras Legislative Council, leaders like C.R. Reddy opposed even an inquiry into the causes of the revolt until it was crushed.

Even the “nationalist” press, as historian Murali Atluri points out, was hostile. The Telugu journal, The Congress , said it would be “gratified” if the revolt could be put down. The Andhra Patrika attacked the rebellion.

Co-option was to come posthumously, as Atluri shows. Once he was killed, the Andhra Patrika sought “the bliss of Valhalla” for Raju. The Satyagrahi compared him with George Washington. The Congress adopted him as a martyr. Efforts to collar his legacy persist. The state government will spend big sums this year on his centenary. Even as some within it seek to amend Regulation1/70 – a move that would further hurt the tribals.

Left: Damaged samadhi of Sitarama Raju. Right: Bust of Sitarama Raju

At Raju’s

samadhi

in Krishnadevipet, the aging caretaker, Gajala Peddappan, has not been paid his salary in three years. General discontent in the area grows daily. Along the Vizag-East Godavari border, pockets of ultra-left influence have sprung up.

“Our grandparents told us of how Sitarama Raju fought for the tribals,” says Pottav Kamraj in Kondapalli. Would Kamraj fight to get back his lands today? “Yes. The police always help the Naidus and the rich when we do. But given the strength, one day we will.”

Maybe the head constable was right to fear an attack on the police station.

It could happen this afternoon.

Cover photo; Dispossessed Koya tribals in Rampa. The land issue is exploding in West Godavari district and simmering here in the East

This story originally appeared in The Times of India on August 26, 1997.

More in

this series

here:

Panimara's foot soldiers of freedom - 1

Panimara's foot soldiers of freedom - 2

The last battle of Laxmi Panda

Sherpur: big sacrifice, short memory

Sonakhan: when Veer Narayan Singh died twice