Her hair is worked hard upon – neatly oiled and plaited. Abundant wrinkles crisscross her face. She is wearing hawai chappals and a khadi saree that falls slightly above her ankles. She looks ready for a day of work, but is here to take us across the Pinnath range to the Rudradhari waterfall – the source of the Kosi river in the Kumaon region.

We are participants at an annual March-April community festival in Kausani, a village of around 2,400 people on the border of Bageshwar and Almora districts of Uttarakhand. Basanti Samant, 60, or Basanti behen , as she is widely addressed, is a speaker at the event. She is not randomly picked to lead our pack.

Some years ago, she led a movement – forming 200 groups, each with 15-20 women – in and around Kausani , to save the Kosi. By 2002, the river’s summer flow had dwindled to around 80 litres a second from 800 litres in 1992, and since then Samant and the women of Kausani have worked hard for its conservation.

Back in 2002, Samant inspired women to stop cutting live wood and start planting more native broadleaf trees such as the banj oak. The women pledged to use water judiciously, and to put out and prevent forest fires. Samant ushered them into a sisterhood that conserves the environment, but over the years, the women have stayed together, deriving strength from each other for battles also fought within their homes.

But, at first, Samant had to fight her own battle.

“My life was like the mountain – difficult and uphill,” she says. When she was around 12 and had completed Class 5, Basanti was married. She moved to her husband’s home in Tharkot village of Pithoragarh district. By the time she turned 15, her husband, a school teacher, died. “My mother-in-law would tell me that I ate him,” she says.

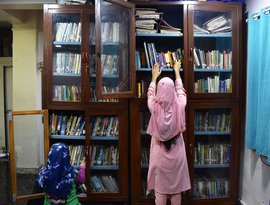

At a meeting of a Kausani women's group – speaking at a government school about the dangers to the Kosi

Soon, she packed her few clothes and returned home to Digara, her village in Pithoragarh, to help her mother and aunts cut grass and collect cow dung. Samant’s father, who worked in the police department in Bihar, tried to get her re-admitted in school. “He wanted me to become a primary school teacher,” she says. But there was strong opposition at home. “If I ever read a book, my mother would taunt me, ‘Will you start working in an office now?’ I didn’t have the courage to oppose her.”

A few years later, Basanti heard about Lakshmi Ashram, a training centre for young women in Kasauni, started in 1946 by Catherine Heilman, a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi. Basanti sent a letter to the ashram asking for admission. “Radha Bhatt, the president, asked me to come,” she says. Her father dropped her to the ashram for a year-long sewing programme in 1980.

Basanti extended her stay to fulfil her father’s dream by teaching in Lakshmi Ashram’s balwadis . She also filled out forms to resume schooling. “I graduated high school [Class 10, through a distance learning course] at the age of 31. My brother distributed sweets all over the village,” she says, beaming at something that happened 30 years ago as if it happened yesterday.

Over time, Basanti started working full-time at the ashram , where she still lives. Her work included helping to form balwadis and women's self-help groups (SHGs) – to teach sewing, handicrafts and other income-related skills – across Uttarakhand. But she longed to go back to Kausani. “I wondered what I am doing in a big city [she was stationed in Dehradun] when I should be with women in the villages,” she says.

She returned to Kausani in 2002 – where the situation was dire. Villagers were cutting trees, unaware of the consequences – each family thinking that their limited use of wood for fuel and agriculture wasn’t amounting to much – and the Kosi was drying up. In 2003, Samant read an article in Amar Ujala saying that the Kosi will die in 10 years if deforestation and forest fires were not controlled – and she propelled into action.

But the problem was fiercer than she had anticipated.

'My life was like the mountain – difficult and uphill': Basanti Samant

The village women would leave before sunrise to bring wood. They would eat a meagre lunch of roti, salt and some rice, and go off to work in the farms. Samant says that often, “previously collected wood would be lying idle, infested with termites” but the women had to fetch more. If they sat at home, “they would get an earful from their husband and in-laws.” The inadequate food and strenuous work meant that the women were spending hard-earned money on medicines with “little or no time to look after their children’s education.”

For Samant, therefore, the objective of forming a self-help group became more than environment conservation. But the women wouldn’t talk to her – largely because the men in their families were opposed to them being involved in any ‘activism’.

One day, Samant saw a group of women near the bus stand in Kausani. Nervously, she approached them. The district magistrate had announced that the Kosi’s water should only be used for drinking, but the women needed it for farming too. The government had not yet constructed canals or check dams in the village. The only approach then was to ensure that the Kosi continued to thrive.

Samant showed them the newspaper cutting and explained the need to plant and save the broadleaf oak trees as opposed to the inhospitable pine planted by the British. She gave them the example of the landmark Chipko movement of the 1970s to conserve forests in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand. She pleaded and cajoled with them to think about how they would water their fields 10 years later. She invoked the visual of a lifeless, waterless Kosi.

Delivering the keynote at the recent community festival

The conversation struck a chord. Around 2003, the women formed a committee, appointed a president, and the cutting of trees gradually stopped in the village. The men in Kausani too began to support the movement. The women still left their house early but this time, to gather drywood. The villagers entered into an agreement with the forest department – the department would recognise they had the first right over wood, but neither the officials nor the villagers would cut trees. It set a strong precedent and committees of women were formed in several nearby villages.

Even

after this victory, challenges gushed out rapidly. For example, despite the

government orders, around 2005, a local restaurant’s owner was siphoning off

Kosi’s water. The women phoned Basanti

behen

. She told them to not let the tanker

pass. By then, the movement had become strong and visible, and so when the

women sat down in protest, the owner relented and agreed to pay a fine of Rs.

1,000, which went into the SHG’s funds.

But it wasn’t just

the villagers or the tourism industry at fault. A forest official was

stealthily running a wood business and would often arrive with his workers to

cut trees. One day, Samant and the women confronted him. She told him, “You’ve

never planted a single sapling and you come here and steal our wood.” The women

were united. They were numerous. They persisted for months. They demanded a

written apology – he refused. They threatened to complain against him. The fear

of losing his job finally made him stop.

Since then, the local groups have not just been forest watchguards, they’ve also tried to address many instances of alcoholism and abuse within the home by intervening or counselling the woman on how to handle the situation. While problems persist, 30-year-old Mamta Thapa, of one of the Kausani SHGs, says, “I’ve found a platform for discussion and possible remedies.”

In 2016, Samant was awarded the Nari Shakti Puraskar by the Ministry of Women and Child Development – she proudly received it from former President Pranab Mukherjee. She continues to fight to save the Kosi and is now also working on waste segregation and talking to hoteliers in and around Kausani about recycling their dry waste. But her biggest contribution, she says, is "ensuring that women are not silent – neither in their local committees or the gram sabha , nor inside their homes."

The author would like to thank Threesh Kapoor and Prasanna Kapoor, the organisers of the Buransh Mahotsav, for arranging the interview.