You can tell from a distance that it's neither a village nor a fairground.

Tens of thousands of cows, bulls and buffalo are grunting and mooing inside rows and rows of bamboo and tin sheds. Hundreds of people are bustling about, and fodder-laden bullock carts keep coming and going.

The stench of methane pervades the air as you pick your way through a minefield of dung.

Welcome – if that's the right word – to one of Maharashtra's biggest “cattle camps,” which has all the commotion and expanse of a fairground but little of its joy or colour.

Rows of tin and bamboo sheds house more than 5,000 cattle at the Palvan camp, not far from Beed town

But what this 100-acre tract of land, about a kilometre from Palvan village in drought-stricken Marathwada, has in abundance is grit.

It’s reflected in the words of Vishnu Baglane, 28, one of the hundreds who have moved in with their cattle from villages far and near, drawn by the free sheds, water and fodder for their animals, and free lunches for themselves. All provided by a non-governmental organisation, with state government help, at a time when successive droughts have left the earth parched and the fields barren.

“I tell myself several times a day not to give up,” Vishnu says, splashing a mug of water on one of his 20 animals in temperatures approaching 45 degrees. “It’s just a matter of hanging on for a few more months.”

He is hoping this monsoon will be good.

Vishnu and his father, Raghunath Baglane, 64, have been here since September, after the fourth straight failed monsoon in Marathwada. The son tends to the cattle from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.; the father arrives after dinner to sleep in the cowshed through the night.

The women of the family often come visiting from their home in Kakadhire, five kilometres away, bringing the children who prance about the place. Sometimes, close relatives drop by, too.

A long history of chara chhaonis

Cattle camps or chara chhaonis have had a long history in Maharashtra and Karnataka as a short-term drought measure, apparently starting from Shivaji's reign in the 17th century. Since 2011, they have become a part of the summer landscape in Maharashtra, particularly in its dry central and western belts.

But last year was the first time that some of them stretched till winter and on to the new year, and were still continuing through this summer.

Social organisations or sugar factories lease farmland denuded by drought and set up these camps, running them with help from the state government or goodwill-seeking political parties.

Some 350 cattle camps sheltering nearly 250,000 animals were operating in Marathwada's three worst-hit districts: Latur, Osmanabad and Beed. Of these, Beed accounts for 265 camps, small and big, Osmanabad had 80-odd and Latur just one.

The camp at Palvan, 15 kilometres from Beed town, harbours about 5,000 small and big animals, belonging to around 300 farmers from 32 villages.

Some of the cattle owners shuttle between their villages and the camp. But some have moved in lock, stock and barrel, sleeping in the cowsheds or tents, and a few have come with their children

It's run by a multipurpose society, the Yashwant Bahuuddeshiya Sevabhavi Sanstha of Rajendra Mhaske, aide to local politician Vinayak Mete, who two years ago switched loyalties from the Nationalist Congress Party to the Bharatiya Janata Party.

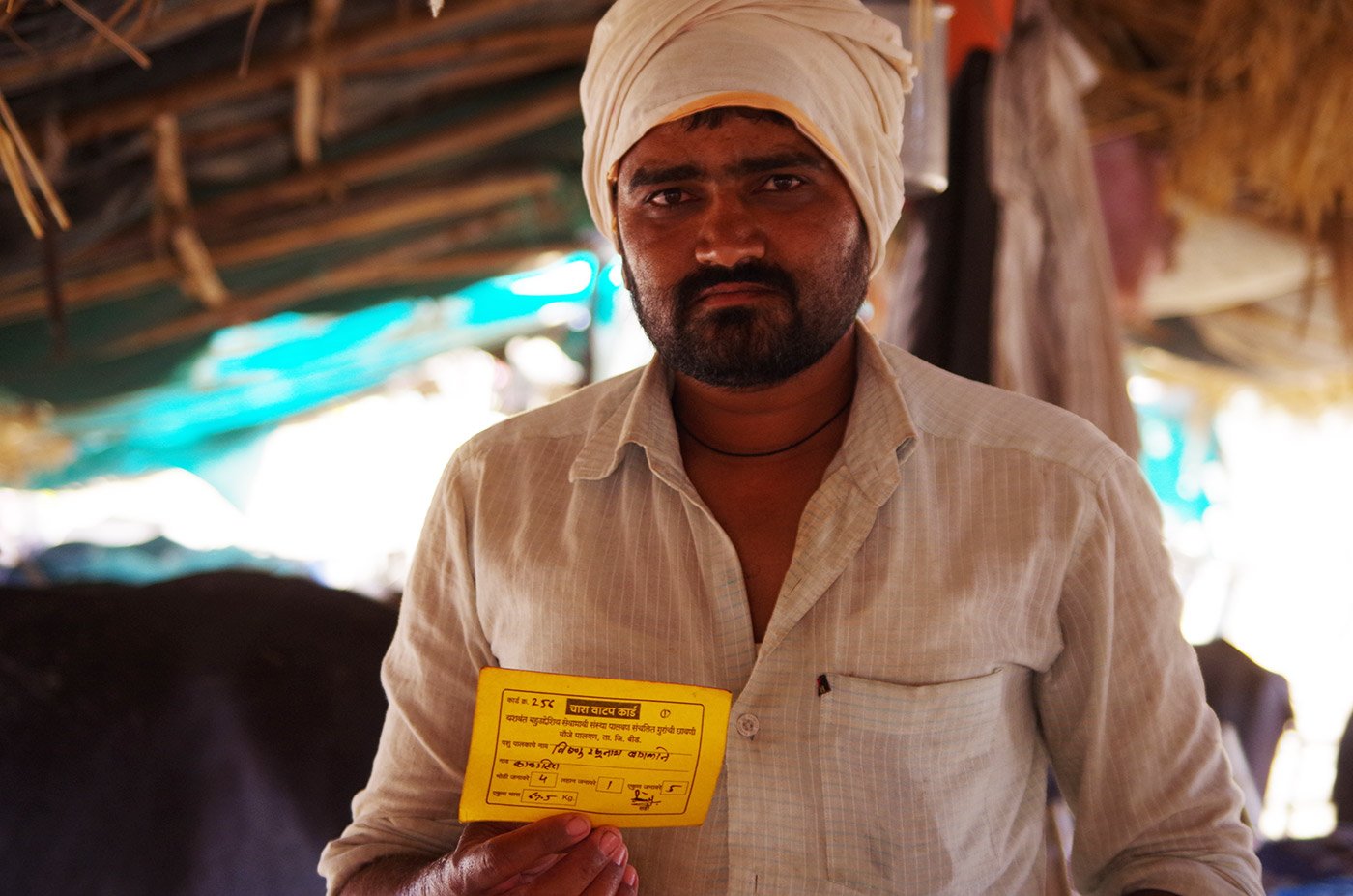

With a staff of 65, the camp is managed well. Each resident, like Vishnu, has been issued an identity card, a daily coupon and a fodder quota based on the number of animals in his shed. Each farmer is given a serial number when the camp office starts distributing fodder, so that there’s no crowding or chaos.

Vishnu Baglane with his ID card at the Palvan camp, where he has been tending to his cattle for months

Some of the cattle owners keep shuttling between their villages and the camp; the rest have moved in lock, stock and barrel, sleeping in the cowsheds or tents.

Savita Munde, for instance, came from Chikhalbed, 60 kilometres away, along with her husband, two children and four cows, six months ago. She tends to the cattle while her husband Sachin works as a camp labourer. “We’ll be here until the monsoon arrives,” she said last month. (The monsoon has now arrived in Marathwada.)

Like a village, the camp has developed its own community life. It recently hosted a mass wedding where 50-odd couples from among the residents’ families tied the knot.

Distress and challenges

The government gives Rs. 63 per big animal and Rs. 30 per small animal per day but camp supervisor Satish Shelke says this is peanuts.

Palvan cattle camp supervisor Satish Shelke’s biggest challenge was to find water and fodder during the dry summer

“We have to spend a lot from our own kitty,” he says, “but if you stand by people in bad times, they will stand by you.”

Shelke’s biggest challenge this summer has been finding water and fodder (sugarcane and green foliage).

“We need 3 lakh litres of water every day. A 12,000-litre water tanker costs Rs. 1,500,” he says. So, the camp spends Rs. 37,500 on 25 water tankers every day.

Add to that the cost of fodder, the free lunches for up to 400 people and other expenses, and the monthly bill runs into several crores, he claims. “We raise most of it from our own businesses and donations.”

Up to 400 free meals are cooked at the camp every day

The Palvan camp brings the fodder from sugarcane-rich Satara, Kolhapur and Ahmednagar, and the green feed from other states.

“This year has been bad, there’s no fodder anywhere,” says the supplier, Shrimant Bapu Gursale, 67. “The sugar factories aren’t allowing farmers to cut their cane and sell it to us, fearing a cane shortage that could hurt their production next year.”

Sugar factories didn't allow farmers to cut and buy cane, fearing a shortage that could hurt their production next year – this aggravated the difficult search for fodder

He adds: “The farther you go in search of fodder, the more you have to spend. The transport cost rises, so does the wastage.”

In 2012-13, Maharashtra had about a million animals lodged in cattle camps across Marathwada and the west of the state. The state BJP government is under fire from the opposition and ally Shiv Sena because this year the camps are confined to just three districts.

But the government has been reluctant to support too many fodder camps because of allegations of corruption and mismanagement in the past.

In many places, therefore, farmers are being forced into distress sales of cattle.

One of them is Baba Jadhav, who rears and sells the expensive Devni breed of cows at Ambewadi village in Latur district, about 250 kilometres from Palvan. The 45-year-old has won many awards for his cattle breeds, but unable to feed his cows this year, he has had to give away nearly a dozen of them to his friends in Pune.

“I sell a dozen cows and buffalo every year, each animal fetching me a handsome price. But this year’s drought will hurt me for at least two more years [the time taken to rear a calf],” Jadhav says.

At least half the animals in his village have been sold at throwaway prices from January to April, some to farmers from other states.

Vishnu says he is indebted to the Palvan camp organisers for saving his 10 cows, two bullocks and eight buffalo after the failure of his summer and winter crops.

The young farmer has already seen many droughts and knows this will not be the last. But at the moment, his goal is to keep his animals alive.

“An animal saved today,” he says, “is an animal earned tomorrow.”

This story was originally published in The Telegraph on June 21, 2016.