“We did not want to move out. In the beginning, we ignored them. Then, whenever the forest officials came, we would hide…. We passed many days like this,” recalls Babulal Kuandhar, who used to live in Talgaon village. “I think the decision was made around 2008. The forest officials told us that the number of tigers in the forest has increased and we must move out immediately.”

In 2012, after four years of refusing to shift, the Adivasis of Talgaon were forced to leave their ancestral village and settle in Sarathpura hamlet, around 16 kilometres away. The hamlet, locally referred to as Tara-Tek, is close to the highway that leads to Amanganj tehsil of Panna district.

In 2008-2009, when the Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh had lost all its tigers, 12 villages were relocated to create inviolate spaces for critical tiger habitats. Talgaon was one of them. A 2011 report says there were 16 villages in the core area of the reserve (11 in Panna district and five in Chhatarpur district; the present status of the four villages that were not relocated at the time could not be verified).

Census 2011 records 171 families in the then Talgaon, most of them from the Raj Gond Adivasi community. Of these, only 37 households remain in Sarathpura. The others migrated to towns like Satna, Katni and Ajaigarh.

However, this relocation bypassed numerous norms and legal provisions. Section 4.9 of Project Tiger , supervised by the Ministry of Environment and Forests, offers two options for the relocation package: a family can accept Rs. 10 lakhs as compensation and take care of the relocation on its own, or the forest department and collector must undertake the rehabilitation process.

Left: Babulal Kuandhar’s house in Sarathpura hamlet; 'We did not want to move out'. Right; Shoba Rani's house; 'Where will we go if they displace us again?'

The people of Talgaon were not given the second option, though they say they had land titles and had been living in that village for generations. They identified another location themselves for resettlement. And now, in their new homes in Sarathpura, the villagers don’t have land titles and worry about eviction.

“We spent half the [compensation] money on building our houses. For six months, we lived in makeshift homes. We don’t even have the patta [titles] for this land, where will we go if they displace us again?” asks Shoba Rani Kuandhar, Babulal’s mother.

Many of the Talgaon families did not even receive the entire compensation amount. “Some accepted the offer [of Rs. 10 lakhs] in the beginning and left for towns and cities. But without land, what use is the money for our survival outside the jungle? So, some of us refused,” Babulal says. The families that resisted – the 37 now in Sarathpura – eventually received only Rs. 8 lakhs per family. It is not clear why this amount was reduced. In return, they left behind in Talgaon their pucca houses and an average of six acres per family, including agricultural and homestead land.

Section 38 (V) of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, mandates the informed consent of villagers before any resettlement. This too was ignored in Talgaon. “They [the forest department] harassed us every day. On some days, they would bring old tiger skins and threaten us that they will file a fake case against us for poaching tigers. I was even imprisoned once for a few days because they said I killed a sambar deer,” says Deelan Kuandhar, a daily wage labourer and Babulal’s neighbour. “One day, they brought elephants to destroy our homes. What else could we do after that?”

'One day, they brought elephants to destroy our homes. What else could we do after that?' says Deelan Kuandhar (left); he too now lives in Sarathpura (right)

Another Sarathpura resident, Bharat Kuandhar, recalls a time when his skills were crucial for tiger conservation. “I used to help the forest department with bringing runaway tigers back to the reserve and fitting their radio collars. The people of the forest are not scared of the tigers, we walk side by side.”

This cohabitation is protected by the Forest Rights Act, 2006 . Sections 4(2)(b) and 4(2)(c) of the Act say it is important to establish that the presence of forest dwellers is causing considerable damage to the wildlife species, and to prove that other options of co-existence are unavailable.

It is unclear if any such options were explored before the relocation. When I contacted the forest department, I was told that all the information is available on the department’s website. But the website does not contain any information about the resettlement procedures for the people of Talgaon or for other villages in the buffer and core areas.

Section 38 (V) of the Wildlife (Protection) Act also says that “the State Government shall, while preparing a Tiger Conservation Plan, ensure the agricultural, livelihood, developmental and other interests of the people living in tiger bearing forests or a tiger reserve.”

Like work, rations and school, water too is a problem in the new hamlet; the two handpumps dry up in the summers and the women have to walk for hours to collect water from nearby Tara village

This too was overlooked. The move to Sarathpura adversely affected the Adivasis’ livelihoods, which were linked to the forest ecosystem. In Talgaon, Babulal’s family had cultivated urad and maize on around five acres. In summers, like other families, they collected and sold mahua flowers (for a local brew), tendu leaves (used for making beedis ) and chironji seeds (usually used in kheers ). The Kuandhar community’s traditional occupation was collecting and selling the bark of the khair or catechu tree, an important ingredient in the preparation of paan .

The relocation ruptured these traditional livelihoods. Now, whenever work is available, Babulal Kuandhar earns Rs. 200-250 a day as a farm labourer in the nearby village of Tara, or by working at construction sites across Amanganj tehsil , where contractors negotiate the daily wages.

“We had everything back then in the forest – tendu, mahua, chironji , everything was there. In summers we collected and sold them. But now the rangers don’t allow us to enter the forest to even collect firewood,” Babulal’s mother Shoba says.

After losing their farmland in Talgaon, Bharat Kuandhar and his two brothers also leased five acres in Sarathpura, where they now cultivate urad , wheat and maize. Bharat takes care of the farm and works at construction sites in Amanganj and Panna town when work is available. His brothers are migrant labourers, working mostly at construction sites in cities such as Delhi and Sonipat. Like them, after the harvest in September, many from Talgaon migrate to other states in search of daily wage work.

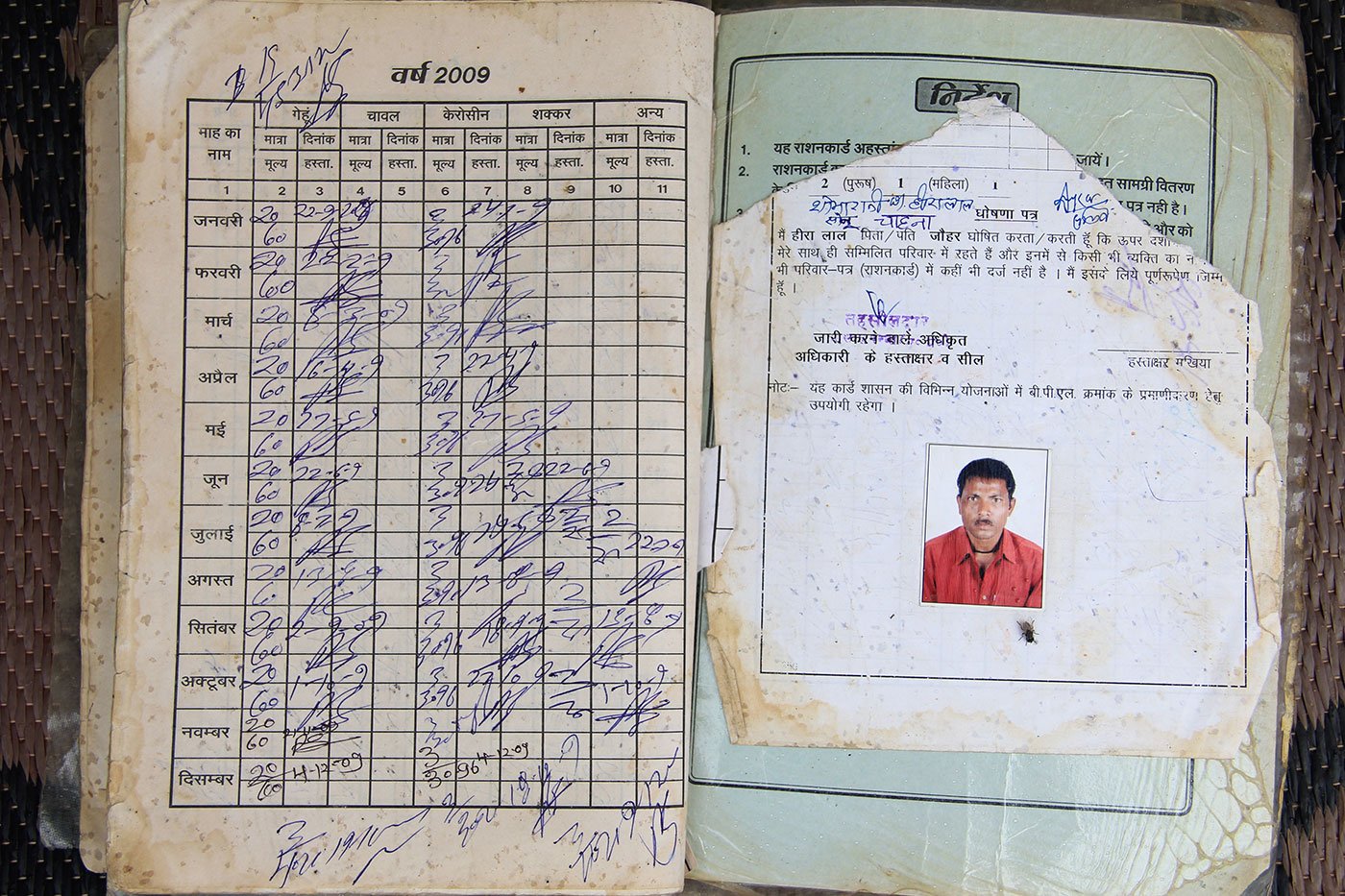

Left: The anganwadi in Tara village is too far for Sarathpura's little kids. Right: Shoba Rani's old family ration card; she has not managed to get a new one

Another pressing issue for the people of Sarathpura is that the hamlet does not come under any panchayat , though soon after the resettlement it should have been integrated with the panchayat of Tara village. So basic entitlements like rations are not available. Shoba Rani has her family's old ration card, issued in 2009. “We have never received any rations from the government for nine years,” she says. They should get five kilos of wheat and rice per person every month, among other items. But the families here purchase rations from the market in Amanganj, which creates a huge dent in their modest earnings. “I filled the form [for a ration card] many times, but it’s of no use,” Shoba Rani adds. “Nothing happens.”

Not being part of a panchayat also means that Sarathpura does not receive any panjiri (supplementary food packets for 0-5 year old children) from anganwadis . “There is still no budget allotted for the children of Talgaon. Very rarely, when panjiri is available in surplus, we give them. Otherwise, we have nothing to offer,” says Gita Adivasi (this is how she prefers to use her surname), the sarpanch of Tara.

Most of the kids in Sarathpura don’t even attend the anganwadi because of the distance – it’s in Tara village, around 1.5 kilometres away. A few older kids manage to go to school there, but education has taken a major hit.

Pyari Bai Kuandhar, 50, Bharat’s mother ( in the cover image on top, outside her house in Sarathpura with her grandchildren ) points to a vacant plot at the end of their settlement and says “This is where I will build an anganwadi if I become the sarpanch of this village one day.”

Meanwhile, the shadow of eviction continues to cloud the daily lives of the people of Sarathpura, as do memories of their ancestral village in the forest