Dilawar Shikalgar smiles as he remembers an incident from the mid-1960s. Someone was hammering at a piece of iron in his workshop, and the swarfs flying off it injured his left forefinger. More than five decades later, the mark of that long-healed wound is still visible, and he says, with a smile, “Look at my palms. They have become metallic now.”

In those five-plus decades, 68-year-old Dilawar has hammered at incandescent iron and carbon steel (an iron-carbon alloy) at least 500 times a day – and in some 55 years has hit his traditional five-kilo ghan (hammer) on metal nearly 8 million times.

The Shikalgar family of ironsmiths, who live in Bagani village in Walwa taluka of Sangli district, have been doing this for more than a century now – making by hand various tools that are used in houses and fields. But they’re best known for hand-crafting some of the finest nut cutters or adkittas (in Marathi) – distinctive in their design, durability and sharpness.

These nut cutters range in size from four inches to two feet. The smaller adkittas are used to cut supari (areca nut), kaath (catechu), khobra (dried coconut) and sutli (coir string). The bigger cutters are used to dissect gold and silver (for use by goldsmiths and jewellers) and big areca nuts, which are sold in the market in smaller pieces.

The nut cutters made by the Shikalgar family have for long been so reputed that people from close and far have travelled to Bagani to buy them. They’ve come from Akluj, Kolhapur, Osmanabad, Sangole, and Sangli in Maharashtra, and Athni, Bijapur, Raybag in Karnataka, among other places.

Dilawar Shikalgar – here with and his son Salim – uses a hammer to shape an iron block into a nut cutter or adkitta of distinctive design and durability

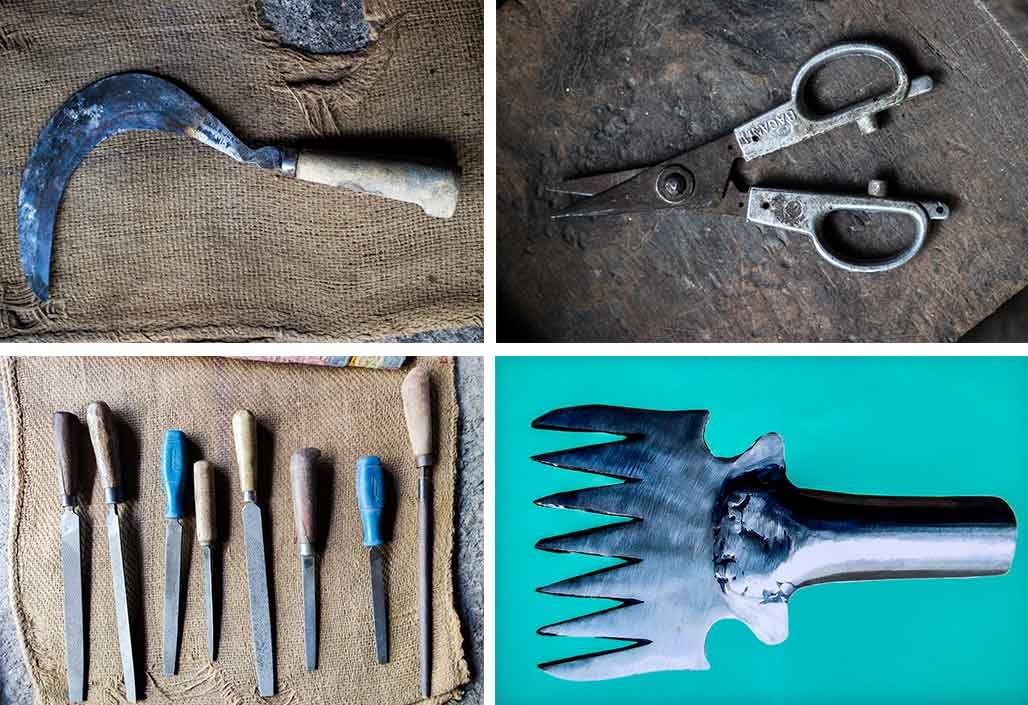

“I’ve lost a count of the adkittas I’ve made,” says Dilawar. He’s also made tools like khurpi (small sickle), vila (sickle), vilati (vegetable cutter), kadba kapaychi vilati (blade to cut chaff), dhangari kurhad (blades for pastoralists’ axes), gardening scissors, grapevine-cutting scissors, patra kapaychi katri (roofing sheets cutter), and barcha (a serrated tool to kill fish).

Dilawar is the oldest among only four ironsmiths who still practice this trade in Bagani, along with his 41-year-old son, Salim. (The other two are Salim’s cousins, Harun and Sameer Shikalgar.) In the 1950s and ’60s, Dilawar says, there were 10-15 of them in his village. Some passed away, others have restricted themselves to making agricultural tools because the demand for

adkittas

has decreased, and making them demands time and patience, but does not fetch a good price, says Dilawar. “This is a job that requires lots of skill and hard work.”

He has made sure that his son Salim, continues the family occupation – the sixth generation of Shikalgars keeping their metal art alive. “Where are the jobs now?” he asks. “Skills never go waste. What will you do if you don’t get a job?

Dilawar first started making nut cutters with his father Makbul at the age of 13. Makbul was running short of helping hands, so Dilawar had to drop out of school after Class 8 and join the family trade. Back then, each adkitta was sold for Rs 4. “In two rupees, we could go to Sangli city by bus then and even watch a film,” he recalls.

And then he recalls another story that his late father had told him: British officials, awestruck by the Shikalgars’ art of making adkittas , had organised a gathering of craftspeople (of the Sangli princely state) to display their handicrafts in Miraj (roughly 40 kilometres from Bagani). “They had invited my great-grandfather, Imam Shikalgar. After seeing his adkitta , they asked if he had made it using any machines.” Imam said no. A few days later, the officials called him again – they wanted to see that fine adkitta again. “They asked him that if he were given all the required materials, would he be able to make an adkitta by hand in front of them?” He immediately said ‘yes’.

Dilawar (left) meticulously files off swarfs once the nut cutter’s basic structure is ready; Salim hammers an iron rod to make the lower handle of an

adkitta

“There was another craftsman who went to that exhibition with his pliers. When the British officials asked him the same question, he ran away, saying that he had made the pliers using machines. That’s how clever the British were,” says Dilawar, laughing. “They knew how important this art was.” Some took nut cutters made by his family with them back to the UK – and some of the Shikalgar adkittas even travelled to the USA.

“A few researchers had come from America to study the [1972] drought here, in the villages. They even had a translator with them.” These scholars, Dilawar tells me, visited a farmer in Nagaon, a nearby village. “After serving them tea, the farmer pulled out an adkitta and started cutting supari .” Intrigued, they asked him about the cutter and discovered that it was made at the Shikalgars’ workshop, where they then landed up. “They asked me to make 10 adkittas ,” Dilawar says. “I completed them in a month and charged [a total of] Rs. 150. As a kind gesture, they gave me Rs. 100 extra,” he says with a smile.

Even today, the Shikalgar family still makes 12 different kinds of adkittas . “We even customise as per the order,” says Salim, who did an Industrial Training Institute (ITI) course in machine tools grinding in Sangli city, and started assisting his father in 2003. His younger brother, Javed, 38, who wasn’t quite interested in the family trade, works as a clerk in the Latur city irrigation department.

Though both men and women in western Maharashtra work as ironsmiths, in Bagani village, says Dilawar, “From the beginning, only men have been making adkittas .” Dilawar’s wife, Jaitunbi, 61, and Salim’s wife, Afsana, 35, are both homemakers.

As he begins work on an adkitta , Salim says, “You won’t find any Vernier callipers or scales here. The Shikalgars never wrote down measurements either. “We don’t have to,” says Dilawar. “ Aamchya najret basla aahe [We can gauge the measurements visually].” The upper handle of the nut cutter is made using a kaman patti (a leaf spring made of carbon steel) and the lower handle is made of a lokhand sali (iron rod). A kilo of leaf spring, purchased in Kolhapur or Sangli city, each around 30 kilometres from Bagani, costs Salim roughly Rs. 80. In the early 1960s, Dilawar would buy a kilo of this spring for just 50 paise.

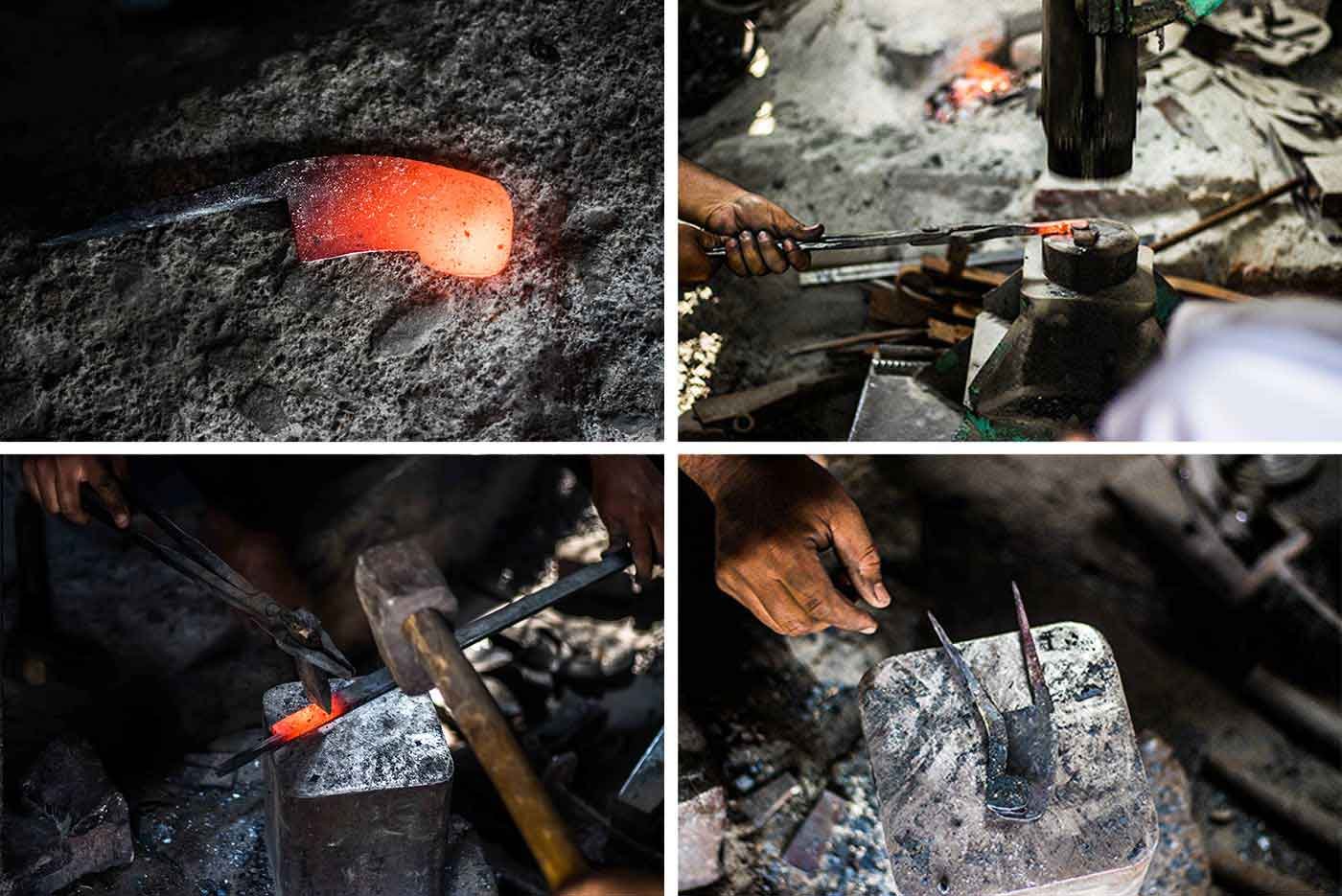

After removing it from the forge, the red-hot carbon steel (top left) is hammered by a machine for a while (top-right). Then it is manually hammered using a ghan or hammer (bottom left) to shape it into a nut cutter (bottom right)

The work day for father and son usually begins at 7 a.m., and continues for at least 10 hours. Salim starts by heating the carbon steel in the forge and then switches on the forge blower. A few minutes into this, he swiftly lifts the red-hot carbon steel with flat tongs and places it under a hammering machine. Before he brought this machine in Kolhapur in 2012 for Rs 1.5 lakh, the Shikalgars used to hammer by hand, risking their bodies and bones every day.

After the machine hammers the carbon steel for a while, Salim places it on a 50-kilo iron block. Then, Dilawar starts hammering it manually and precisely, to shape it into a nut cutter. “You can’t give it the exact shape on a machine,” Salim explains. This process of hammering and forging takes around 90 minutes.

Once the nut cutter’s basic structure is ready, Dilawar uses a vice to secure the carbon steel. Then, he meticulously files off small swarfs using different kinds of kanas (filing tools) bought at a hardware store in Kolhapur city.

After reviewing the adkitta ’s shape multiple times, he begins sharpening its blade. So fine is his chiselling that the nut cutter then needs to be re-sharpened, he says, only once in 10 years.

It now takes the Shikalgars about five hours to make one adkitta . It took twice the time before, when they did everything by hand. “We’ve divided the work so that we can make things fast,” says Salim, who does the forging, beating and shaping of the metal piece, while his father focuses on filing it and sharpening the blade.

Dilawar also makes and sharpens tools other than

adkitta

s

.

'This side business helps us feed our family', he says

The ready adkitta is sold for anywhere between Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,500, depending on its design and size. A two-feet long adkitta can cost Rs. 4,000 to Rs. 5,000. And how long will this nut cutter last? “ Tumhi aahe toh paryant chaltey [It will last till the time you are around],” Dilawar says, with a laugh.

But not many come looking for these sturdy Shikalgar adkittas now – from at least 30 nut cutters in a month in the past, their sales are down to barely 5 or 7. “Earlier, a lot of people used to eat paan . For this, they would always cut the supari ,” says Dilawar. Younger people in villages don’t eat much paan nowadays, Salim points out. “They have moved to guthka and paan masala .”

Since it’s difficult to earn enough by just making the adkittas , the family also makes sickles and vegetable cutters – about 40 a month. Dilawar also sharpens sickles and scissors, and charges between Rs. 30 and Rs. 50 for each. “This side business helps us feed our family,” he says. He also gets a bit more from leasing the family’s half acre of land to a farmer who grows sugarcane.

But the sickles the Shikalgars make have to compete with cheaper varieties, of substandard material and quality, says Salim, made by local ironsmiths. These are available for around Rs. 60, while the Shikalgars price their sickles at Rs. 180-200. “People now treat things like use-and-throw [objects], and that’s why they want them cheap,” he explains.

“And not all ironsmiths can make adkittas ,” he adds. “ Jamla pahije ” – You must have what it takes.

The Shikalgars make tools like sickles (top left), grapevine-cutting scissors (top right) and

barcha

s (a serrated tool to kill fish; bottom right). They use different kinds of

kana

s (filing tools) to shape the

adkitta

There are other daily challenges too. One is the possibility of injuries or illness. Their family doctor has advised the Shikalgars to use a metal face shield while working, so that they don’t inhale any carcinogens. But they only use a layered cotton mask and sometimes wear gloves. They say that, fortunately, no one in the family has suffered a work-induced illness so far – though that injured forefinger of Dilawar speaks of the occasional mishap.

Every month, they pay an electricity bill of at least Rs. 1,000 for the workshop, but there are 4 to 5 hour long breaks in the electricity almost every day. The hammering machine, and another one they use for sharpening, must then remain switched off, forcing them to lose work hours and income. “There’s no fixed time when the electricity goes off,” Salim says. “Nothing can be done without electricity.”

Despite the odds, retaining high standards in whatever they make matters greatly to the Shikalgars, as does the reputation of their nut cutters. “Bagani has a legacy of adkittas ,” says Salim, who hopes his 10-year-old son Junaid, now in Class 4, will eventually continue the Shikalgar legacy. “People come from far for them, and we don’t want to disappoint anyone by making cheap adkittas . Once sold, a customer shouldn’t come back with any complaint.”

Dilawar too, despite the falling demand, continues to draw pride from his family’s generations-old craft. “This is the kind of work where people will come looking for you, even if you work in the mountains,” he says. “Whatever we have today is because of adkittas .”