It isn’t the sunset she waits to see. Sitting outside her one-room kitchen, Randawani Survase stares into oblivion long after twilight gives way to streetlights. With a sad smile on her face, she says, “This is exactly where my husband used to sit and sing his favourite abhang .”

Singing devotional poetry praising the Hindu god Vitthal was a favourite pastime of her husband, Prabhakar Survase. He had retired as a clerk from the Maharashtra State Road Transport Corporation two years ago, when he turned 60. Since then, every evening at their home in Parli, a town in Maharashtra’s Beed district, Prabhakar would sing and bring cheer to his neighbours.

Until he started showing signs of Covid-19 on April 9, 2021.

Two days later, Prabhakar was admitted to Swami Ramanand Teerth Rural Government Medical College, Ambejogai (SRTRMCA), located 25 kilometres from Parli. Ten days after that, he died gasping for breath.

His death was rather sudden. “At 11:30 in the morning, I fed him biscuits,” says Vaidyanath Survase, his 36-year-old nephew who runs a Chinese fast food stall in Parli. “He even asked for juice. We chatted with each other. He seemed fine. At 1:30 in the afternoon, he was declared dead.”

In the intervening hours, Vaidyanath was present in the hospital ward. The oxygen supply pressure suddenly started dipping sometime in the afternoon, he says. Prabhakar, who was chatty and upbeat until then, began struggling to breathe. “I desperately called the doctors, but nobody paid attention,” adds Vaidyanath. “He struggled to breathe for a while and died soon after that. I pumped his chest, rubbed his feet, but nothing worked.”

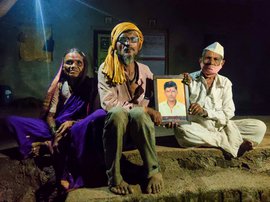

Randawani Survase (left) is coming to terms with losing her husband, Prabhakar. His nephew Vaidyanath (right) believes he died death due to a shortage of oxygen

Prabhakar’s family believes that the hospital ran out of oxygen, which caused his death. “His health did not get worse after being admitted. He was recovering. I did not leave the hospital even for a day,” says 55-year-old Randawani. “A day or two before he died, he even joked about singing in the hospital ward.”

There were other deaths too on April 21 at the hospital. In the short span between 12:45 p.m. and 2:15 p.m., six other patients died at SRTRMCA.

The hospital denied that the deaths were due to a shortage of oxygen. “Those patients were already critical, and most of them were above 60,” said Dr. Shivaji Sukre, dean of the medical college, in a statement to the press.

“The hospital would obviously deny it, but the deaths happened due to oxygen shortage,” says Abhijeet Gathal, a senior journalist who broke the story on April 23 in Vivek Sindhu , a Marathi daily published from Ambejogai. “The relatives were furious with the hospital management that day. Our sources confirmed what the relatives said.”

Cries for help to find oxygen cylinders and hospital beds have been flooding social media in the last few weeks, with people across India’s cities turning to platforms like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram in desperation. But the shortage of oxygen is as dire, if not more acute, in areas where there’s hardly any social media activity.

An official at the Ambejogai hospital, requesting anonymity, said that it's a daily struggle to meet the oxygen demand. “We need about 12 metric tonnes of oxygen per day. But we get 7 instead [from the administration],” he says. “It is a struggle every day to make up for the deficit. So we order jumbo cylinders from here and there.” Apart from suppliers in Beed, says the official, oxygen cylinders are procured from the nearby cities of Aurangabad and Latur.

SRTRMCA is categorised as a Dedicated Covid Hospital by the state government. It has

a total of

402 beds, of which 265 are oxygen-supported. In the late April, an oxygen plant from the thermal power station in Parli was shifted to the hospital to improve its oxygen supply. The hospital currently has 96 ventilators, including 25 from the PM Cares Fund, which were received in the last week of April.

Left: A working ventilator at the Ambejogai hospital. Right: One of the 25 faulty machines received from the PM CARES Fund

The 25 ventilators turned out to be faulty. In the first week of May, two technicians from Mumbai volunteered to travel to Ambejogai, 460 kilometres away, to fix them. They managed to set right 11 that had minor hitches.

Relatives of the patients in Ambejogai know that the hospital is walking a thin line. “When the hospital is scrambling for oxygen in front of you every day, it is natural to be nervous,” says Vaidyanath. “Oxygen shortage is a story across India. I have been following social media and seeing how people are reaching out to each other. We don’t have that option in rural areas. Who will notice if I post something? We are at the mercy of the hospital, and in our case, our worst fear came true.”

Prabhakar's absence is deeply felt by Randawani, their son, daughter-in-law and three granddaughters, aged 10, 6 and 4. “The kids miss him a lot, I don’t know what to tell them,” says Randawani. “He regularly asked me about them in the hospital. He was looking forward to going home. I didn’t think he would die.”

Randawani, who earns Rs. 2,500 per month working as a domestic helper, wants to get back to work soon. “My employers have been kind not to force me to go back to work,” she says. “But I will start soon. It will keep me occupied.”

By May 16, Beed district

recorded

over 75,500 Covid cases and about 1,400 deaths from the infection. The neighbouring Osmanabad district had seen over 49,700 cases and nearly 1,200 deaths.

Both Beed and Osmanabad are in the agrarian region of Marathwada, which accounts for the most number of farmers’ death by suicide in Maharashtra. Large numbers of people have migrated from these districts in search of work. Struggling with a water crisis and debt, people of the region are facing the pandemic with limited resources and an inadequate, overwhelmed health infrastructure.

At the District Civil Hospital in Osmanabad, the situation is not very different from Ambejogai, about 90 kilometres away. Relatives of Covid patients wait under the blistering sun discussing their anxieties with each other. Nervous strangers bond while the administration tries to meet the district’s oxygen demand of 14 metric tonnes a day.

Left: Swami Ramanand Teerth Rural Government Medical College and Hospital in Ambejogai. Right: An oxygen tank on the hospital premises

At the height of the first wave of Covid-19, in 2020, about 550 oxygen beds were needed in Osmanabad district, says Kaustubh Diwegaonkar, collector and magistrate of the district. When the second wave was imminent, the district administration prepared to double the number.

The second wave, starting in February 2021, hit with even more force. The district needed three times the oxygen-supported beds than during the first wave. Currently,

there are

944 oxygen-supported beds, 254 ICU beds and 142 ventilators in Osmanabad.

The district has been procuring medical oxygen from Latur, Beed and Jalna. Oxygen is also being sourced from Ballari in Karnataka and Hyderabad in Telangana. In the second week of May, oxygen was airlifted from Jamnagar in Gujarat to Osmanabad. On May 14, Dharashiv Sugar Factory in Chorakhali, in Osmanabad’s Kalamb

taluka

, became the first establishment in the country to generate medical grade oxygen from ethanol. It is expected to generate 20 metric tonnes every day.

At the Civil Hospital, looking after its 403 beds are 48 doctors and 120 hospital staff that includes nurses and ward assistants working in three shifts. Hospital authorities and police personnel are seen negotiating with relatives of patients who insist on sitting at the patients’ bedside and risk getting infected. Family members of patients often search the hospital for a vacant hospital bed.

When Rushikesh Kate’s 68-year-old mother, Janabai, was taking her last few breaths, someone was waiting in the corridor for her to pass away. His sick relative needed a bed. “As she struggled to breathe and was on the verge of dying, the man made a phone call to someone telling them that a bed would soon become vacant here,” says Rushikesh, 40. “It sounds insensitive, but I don’t blame him. These are desperate times. In his place, I would have probably done the same thing.”

Janabai was admitted to Civil Hospital just a day after his father was shifted there by a private hospital because it was running out of oxygen. “It was the only option before us,” says Rushikesh.

Left: Rushikesh Kate and his brother Mahesh (right) with their family portrait. Right: Rushikesh says their parents' death was unexpected

Rushikesh’s father, Shivaji, 70, fell ill with Covid-19 on April 6, and Janabai developed symptoms the next day. “My father was a bit serious so we admitted him to Sahyaadrie Hospital in the city,” says Rushikesh. “But our family doctor said my mother could be isolated at home. Her oxygen saturation was fine.”

On the morning of April 11, a doctor from Sahyaadrie, a private hospital, called Rushikesh to inform him that Shivaji was being shifted to Civil Hospital. “He was on a ventilator,” says Rushikesh. “His breathing difficulties increased the moment they moved him to Civil Hospital. The transfer caused a lot of exertion,” he says, adding, “He kept telling me he wanted to go back. The atmosphere is better in a private hospital.”

The ventilator at Civil Hospital could not maintain the required pressure. “I sat holding his mask all night on April 12 because it kept falling off. But he was slipping. He passed away the next day,” says Rushikesh. Four more patients who were moved with Shivaji from the private hospital died.

Janabai was brought to Civil Hospital on April 12 with breathing difficulties. She died on April 15. Rushikesh lost both his parents in just 48 hours. “They were fit,” he says, his voice quivering. “They worked hard and brought us up under very difficult circumstances.”

A large family portrait hangs on a wall in the living room of his home in Osmanabad city. Rushikesh, his elder brother Mahesh, 42, and their wives and children, lived together with Shivaji and Janabai. The joint family has five acres of farmland on the outskirts of the city. “Their death was unexpected,” says Rushikesh. “When someone is healthy and exercising daily in front of you, it is tough to come to terms with their absence when they suddenly pass away.”

Outside her home in Parli, Randawani too is trying to come to terms with losing her husband. Every evening, at the very spot where Prabhakar sang his songs, she struggles to accept his absence. “I can’t sing like him,” she says with an awkward smile. “I wish I could.”