The Friday morning of April 1, 2022 was like any other for Rama. She had woken up around 4:30, walked to the village well nearby to fetch water, washed clothes, cleaned the house, and had

kanji

with her mother later. She then left for work, at Natchi Apparel in Vedasandur

taluk

of Dindigul district, 25 kilometres from her village. But by afternoon that day, the 27-year-old and her fellow women workers had created history – after struggling for more than year to end sexual harassment in their garment factory.

“To be honest, I feel like we have done the impossible,” says Rama, about the

Dindigul Agreement

– signed that day by Eastman Exports Global Clothing (the Tiruppur-based parent company of Natchi Apparel) and the Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union (TTCU) – to end gender-based violence and harassment at the factories operated by Eastman Exports in Dindigul district, Tamil Nadu.

As part of this landmark agreement, an ‘enforceable brand agreement’, or EBA, was signed by the multinational fashion brand, H&M, to support and enforce the TTCU-Eastman Exports agreement. Eastman Exports’ Natchi Apparel produces clothes for the Sweden-headquartered clothing company. The agreement signed by H&M is the second such industry contract worldwide, tackling gender-based violence in the fashion industry.

Rama, who is a member of TTCU, a Dalit women-led trade union of textile workers, has been an employee of Natchi Apparel since four years. “I never thought the management and the brand [H&M] would sign an agreement with a Dalit women’s trade union,” she says. “They have taken the right step now, after having committed some really wrong actions.” H&M’s agreement with the union is the first ever EBA to be signed in India. It is a legally binding contract under which H&M is obligated to impose penalties on Eastman Exports if the supplier violates its commitments to TTCU.

But Eastman agreed to come to the table more than a year after the rape and murder of Jeyasre Kathiravel, a 20-year-old Dalit garment worker of Natchi Apparel. Jeyasre had suffered months of sexual harassment by her supervisor at the factory, who belongs to a dominant caste, before she was murdered in January 2021. The supervisor has been charged with the crime.

Jeyasre’s murder sparked outrage against the garment factory and its parent company, Eastman Exports, one of India’s largest clothing manufacturers and exporters, supplying to multinational clothing companies such as H&M, Gap and PVH. As part of the campaign to get justice for Jeyasre , a global coalition of unions, labour groups and women’s organisations had demanded that the fashion brands take “action on Eastman Exports’ escalating coercive actions against Ms. Katharivel’s family”.

A protest by workers of Natchi Apparel in Dindigul, demanding justice for Jeyasre Kathiravel (file photo). More than 200 workers struggled for over a year to get the management to address gender- and caste-based harassment at the factory

What happened with Jeysare, however, was not a stray case. Many women workers of Natchi Apparel have come forward with their own experiences of being harassed after her death. Hesitant to meet in person, some of them spoke to PARI over the phone.

“[Male] supervisors would routinely abuse us verbally. They would scream at us and use very vulgar and demeaning insults if we reported late to work or were unable to meet production targets,” says garment worker Kosala, 31. After passing Class 12, Kosala, a Dalit, started working in the garment industry over a decade ago. “Dalit women workers were the most harassed by supervisors – they would call them ‘buffalos’, ‘bitches’, ‘monkeys’, whatever came to their mouth, if we did not achieve a target,” she adds. “There were also supervisors who would try to touch us or comment on our clothing or make lewd jokes about women’s bodies.”

Latha, a graduate, joined the factory hoping to earn enough to study further. (She and the other garment makers get paid Rs. 310 a day for an eight-hour shift.) But she was left disturbed by the horrific state of affairs at the factory. “Male managers, supervisors and mechanics – they would try to touch us and we had no one to complain to,” she says, breaking into tears.

“When a mechanic comes to repair your tailoring machine, he will try to touch you or ask for sexual favours. If you refuse, he won’t repair the machine on time and you will not be able to meet the production targets – then you will be verbally abused by the supervisor or manager. Sometimes, a supervisor stands next to a woman worker and brushes his body against hers,” says Latha, who travels 30 kilometres from her village to come to work.

The women had no way to seek redress, Latha explains. “To whom can she complain? Who will trust the words of a Dalit woman when she raises her voice against an upper caste male manager?”

“Whom can she complain to?” Thivya Rakini, 42, raises the same question. The state president of TTCU, she led the long campaign to free Natchi Apparels of gender-based harassment. Even before Jeyasre’s death, TTCU, founded in 2013 as an independent Dalit women-led trade union, had been organising workers to end gender-based violence in Tamil Nadu. The trade union represents around 11,000 workers – 80 per cent are from the textile and garment industry – across 12 districts, including the garment hubs of Coimbatore, Dindigul, Erode and Tiruppur. It also fights against wage theft and caste-based violence in the garment factories.

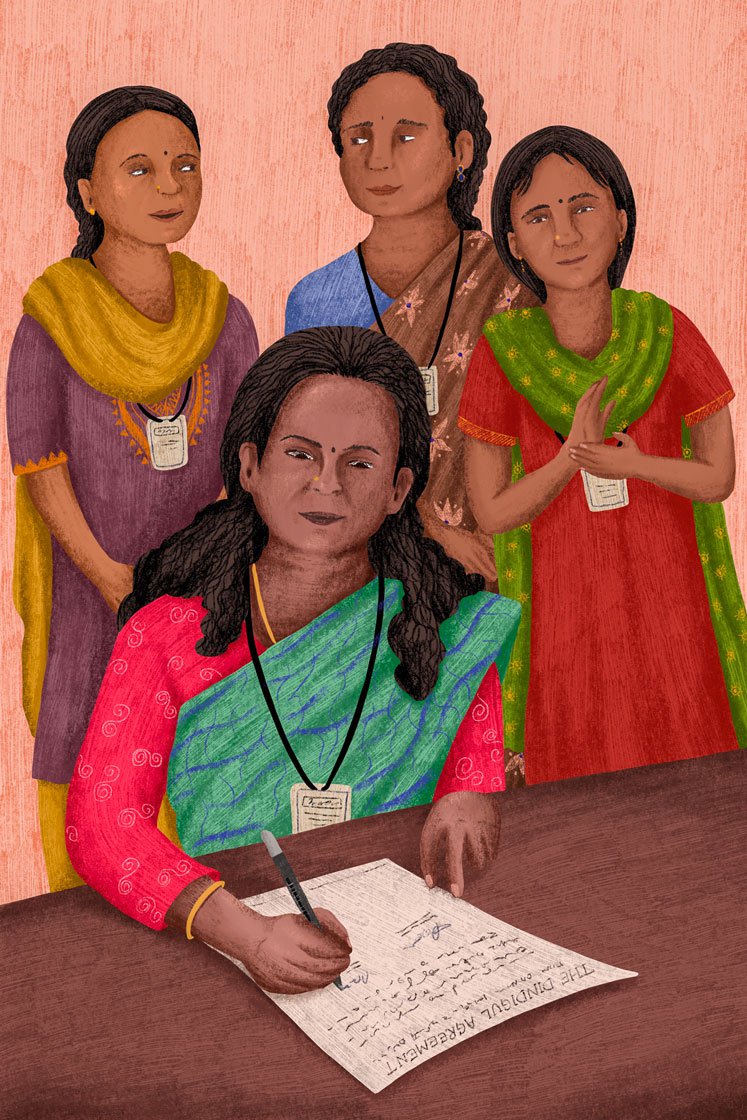

Left: Thivya Rakini, state president of the Dalit women-led Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union. Right: Thivya signing the Dindigul Agreement with Eastman Exports Global Clothing on behalf of TTCU

“Before the agreement, there was no proper internal complaints committee [ICC] in the factory [Natchi],” Thivya says. The existing ICC would police the women’s conduct, adds Mini, a 26-year-old Dalit worker who comes to work from a village 28 kilometres away. “Rather than address our complaints, we were told how we should dress or sit,” she says. “We were prevented from taking bathroom breaks, forced to do overtime work and prevented from using the leave we were entitled to.”

In its campaign after Jeyasre’s death, TTCU not only sought measures to tackle sexual violence, but also raised concerns about the lack of bathroom breaks and forced overtime, among other issues.

“The company was against unions, so most of the workers had kept their union membership a secret,” says Thivya. But Jeyasre’s death was a tipping point. Despite facing intimidation from the factory, workers like Rama, Latha and Mini went on struggle. About 200 women took part in protest rallies for more than a year. Many gave their testimonies to organisations working at the global level to draw attention to the Justice for Jeyasre campaign.

Finally, the TTCU, and two organisations that have spearheaded campaigns to address violence and harassment in interntional fashion supply chains – Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) and Global Labor Justice-International Labor Rights Forum (GLJ-ILRF) – signed the enforceable brand agreement with H&M in April this year.

According to a joint press release by the three organisations, the Dindigul Agreement is the first enforceable brand agreement in India. It is also “the first EBA in the world to include both clothing factories and factories that produce fabric and textiles for use in clothing.”

All the signatories have jointly committed “to eradicate discrimination based on gender, caste, or migration status; to increase transparency; and to develop a culture of mutual respect in the garment factory setting.”

The Dindigul Agreement pledges to end gender-based violence and harassment at the factories operated by Eastman Exports in Dindigul. ‘It is a testimony to what organised Dalit women workers can achieve,’ Thivya Rakini says

The agreement adopts global labour standards and draws from the International Labor Organization’s Violence and Harassment Convention . It protects the rights of Dalit women workers, their freedom of association and their right to form and join unions. It also strengthens the internal complaints committee to receive and investigate complaints, and recommend remediation. Independent assessors are required to ensure compliance, and non compliance will have business consequences for Eastman Exports from H&M.

The Dindigul Agreement covers all workers at Natchi Apparel and Eastman Spinning Mills (in Dindigul), over 5,000 workers in total. Almost all of them are women and the majority are Dalit. “This agreement can significantly improve the working conditions of women in the garment sector. It is a testimony to what organised Dalit women workers can achieve,” says Thivya.

“I do not want to grieve anymore about what happened to me or my sisters like Jeyasre,” says Malli, 31. “I want to look ahead and think about how we can use this agreement to ensure what happened to Jeyasre and others never repeats.”

The effects are showing. “Working conditions have changed a lot since the agreement. There are proper bathroom breaks and lunch breaks. We are not denied leave – especially if we are sick. There is no forced overtime. Supervisors don’t abuse women workers. They are even giving sweets to workers on Women’s Day and Pongal,” says Latha.

Rama is happy. “The situation has changed now. The supervisors are treating us with respect,” she says. She worked full time throughout the workers’ campaign, stitching over 90 pieces of undergarments per hour. The severe back pain she experiences doing this work, can’t be helped, she says. “It is a part of working in this industry.”

Waiting for the company bus to go home in the evening, Rama says, “We can do a lot more for the workers.”

Names of the garment workers interviewed in this story have been changed to protect their privacy.