“Maybe the phone does have my money,” sighed Mula, standing in the hollow of a pond she had helped dig. It was a windy winter morning, and after many months of not receiving her wages, she finally had a clue about them. Or so she thought.

In January 2018, Vikash Singh, the Additional Programme Officer (MGNREGA) of Sitapur had, after repeated protest demonstrations at his office, announced that MGNREGA wages were going to 9,877 accounts opened with Airtel Payments Bank since January 2017. These new accounts, in Singh’s words “were opened without informed and express consent” during the purchase of a new SIM card.

The uninformed consent, obtained by just ticking a box on the online customer acquisition form while doing the ‘Aadhaar-based SIM verification’, resulted in a diversion of benefit transfers to these new accounts. This rode on a seemingly harmless guideline of the Unique Identification Authority of India: that the bank account seeded last with the Aadhaar number automatically becomes the one to receive any money disbursed as a direct-benefit transfer .

Mula, a 45-year-old, unlettered member of the Pasi Dalit community, felt a dull hope at Singh’s announcement. She too had bought a phone with an Airtel SIM card in 2016. One morning, prompted by neighbours mentioning great deals on Airtel SIM cards (a Rs. 40 card with 35 minutes talk time), Mula and her son Nagraj had walked from their village, Dadeora in Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh to the main market in Parsada in Machhrehta block, four kilometres away. At the shop which sold them a mobile phone (and has since shut down) Mula was asked for a copy of her Aadhaar card, since her son did not have one. She produced hers.

Mula's uninformed consent was obtained by just ticking a box on the online form while doing the ‘Aadhaar-based SIM verification’

“There was a small machine. I was asked to press my thumb down on it twice,” she remembers. This was in keeping with multiple government directives, the first of which was made in October 2014 by the Department of Telecommunications. It called for a customer’s Aadhaar number to be entered in the acquisition form filled in at the time of applying for a telephone/ mobile number.

After Mula handed over a copy of her Aadhaar card, the shop-owner asked for some details which he punched into a computer, inserted a SIM card in a mobile and handed it over to the duo. They paid Rs 1,300 and, as they walked back home, an ecstatic Nagraj tried to explain its use to Mula.

Some weeks later, the phone was lost at a wedding. The phone number, which was the key to accessing the account, was eventually forgotten.

Yet, as Mula stood at the block office, protesting against the missing wages of many like her and chanting: ‘ kamanewala khayega, lootnewala jayega, naya zamana aayega ’ [‘the wage earner will eat, the one who loots will go, a new dawn will come’] she hoped that her wages would be found and transferred to her account in Allahabad UP Grameen Bank, Parsada. (The bank branch she had specified in her job application).

However, as January turned to February last year, there was no sign of the wages.

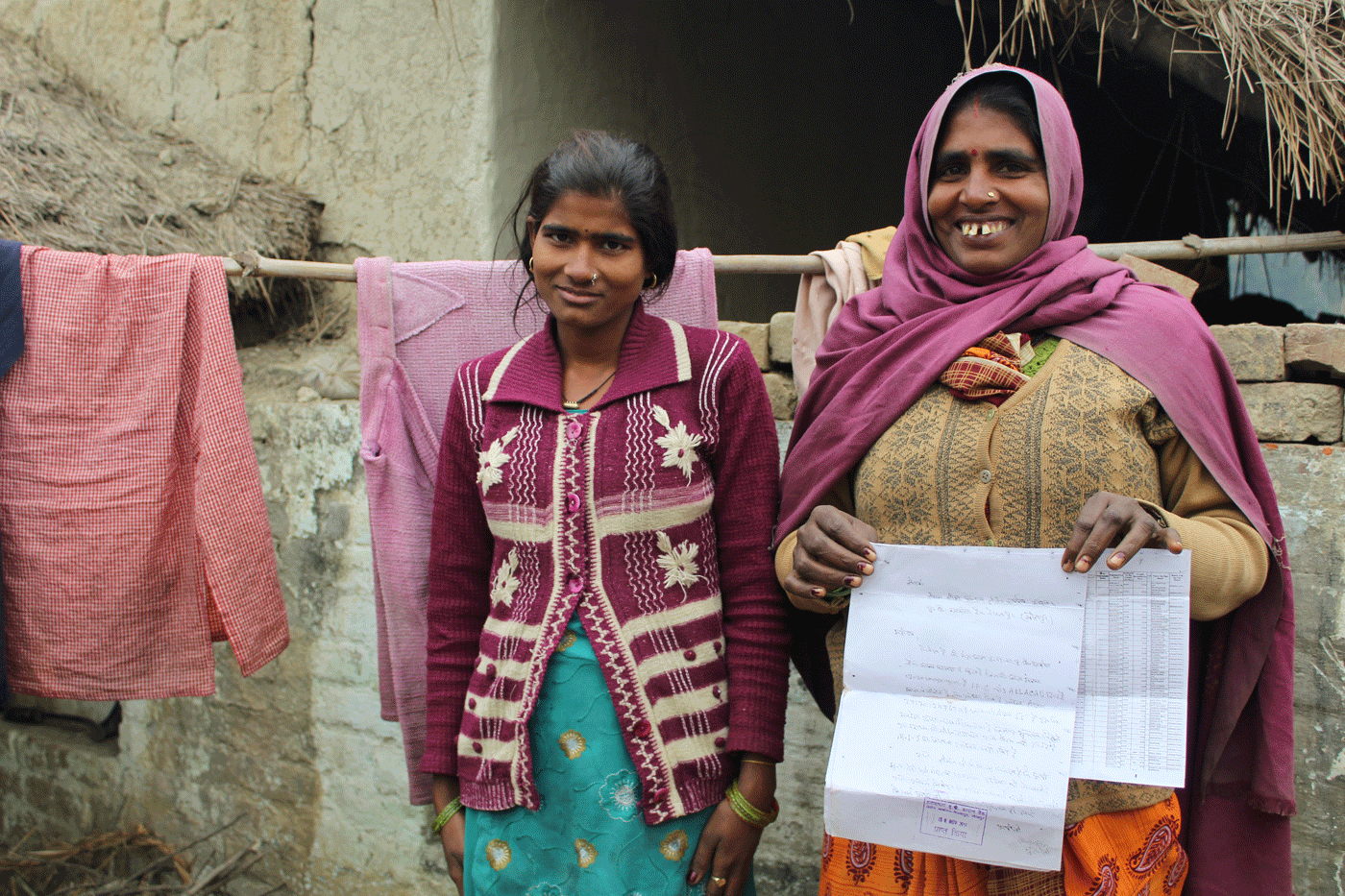

Mula (with daughter Kapoora) holding the application she gave to the block office to inquire about her missing wages

When the MGNREGA wages did not come, Mula borrowed Rs. 15,000 from relatives. The family went on a staple diet of potatoes. At Rs. 10 for a kilo and a half that was all they could afford. Rice or wheat became a rarity. At her modest one-room home, a lone pumpkin was left to hang from the roof, to be eaten when there was no money for even potatoes.

“There were days when we had very little. Pratap would wail so loudly that the entire neighbourhood would know. I have never been so ashamed,” she says.

Somewhere in the midst of her struggles, Mula had opened another bank account. Or rather, another account had been opened for her.

In May 2016, representatives from the Samhita Microfinance Agency had visited Parsada. Amit Dixit, the unit manager who looks after operations in Sitapur (and its neighbouring district Lakhimpur), says, “We explain to the poor how they can be self-employed by forming self-help groups. Since they don’t have money to start their business, we open bank accounts for them to borrow money.” The agency’s website says it ‘serves to bring the poorest of the poor…into the fold with financial inclusion service’.

In a country where less than three in five households have access to banking services (NSSO, 59th Round), such inclusion has been the major focus of successive governments. Since August 2014, 31.83 crore new bank accounts have been opened. These aim to ease the access of the rural poor, like Mula, to credit. However, in the absence of financial literacy, such initiatives achieve little – except compounding the distress of the poor.

Mula has no recollection of opening such an account. Yet, in May 2017, she duly signed a form which landed at the desk of Prashant Chaudhary, the Branch Manager of IDBI Bank, Sitapur. (“I thought I would get some money,” she says). Chaudhary says he receives such signed applications in bulk.

Mula is the principal wage-earner of the family. Her husband Mangu Lal, is infirm

“We have about 3,000 active accounts, opened through the agency, with us. A representative drops off the relevant papers and we complete the formalities. Till a year ago, a copy of their Aadhaar was not necessary. Now it is mandatory. Not all such accounts have loans,” he says.

It was to such an account that Mula’s wages were diverted. Vikash Singh does not respond to why that discovery was not made earlier through the computerised database his office maintains for MGNREGA. But in February, when the protests had started to draw attention, Singh told Mula, among others, where the missing money was.

Mula, who has since withdrawn the money and shut the account is a relieved woman. She does not question the system which brought her such distress.

“The wait was worse than death. I am glad it is over,” she sighs.