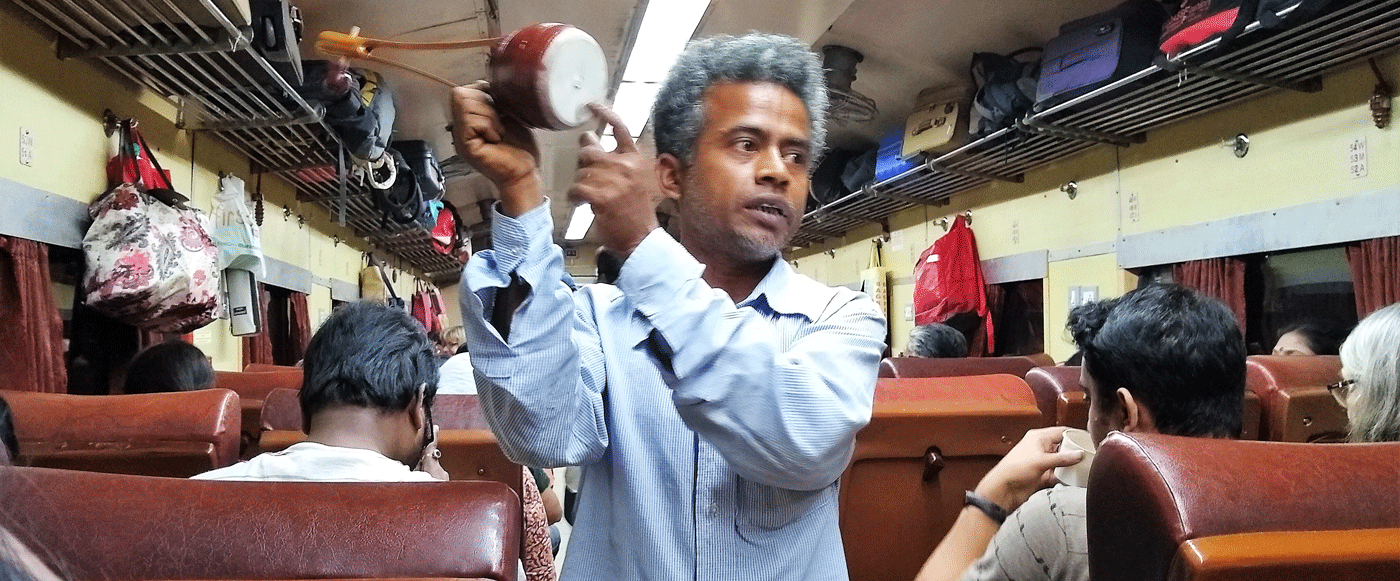

The Hazarduari Express from Beldanga town to Kolkata has just passed Plassey when the sound of an ektara fills the compartment. Sanjay Biswas is carrying a large basket full of artefacts made of wood – a charkha , a table-lamp, a car, a bus – and the single-stringed ektara .

The finely-crafted items stand out amid the Chinese goods on sale – toys, key-rings, umbrellas, torches, lighters – and other vendors selling handkerchiefs, almanacs, mehendi booklets, jhaal-muri , boiled eggs, tea, peanuts, samosas, mineral water and more. Each vendor on these trains has a designated route and compartment.

The passengers bargain hard for the best deals. The hawkers do brisk business during the two hours that the train takes to cover the 100 kilometres between Beldanga in Beharampore subdivision of Murshidabad district and Ranaghat. Most of the vendors get off at Ranaghat, a few at Krishnanagar, both major railway junctions on this line. From there, many take connecting local trains to their villages and towns.

Someone asks Sanjay for the price of the ektara . Rs. 300, he says. The potential buyer holds back. “This is not a cheap toy, I create these with utmost care,” Sanjay says. “The raw materials are of the highest quality. What you see at the bottom of the ektara is pure leather.” Another passenger argues: “We get these in local fairs at much cheaper price.” Sanjay replies, “This is not the cheap one that you get at the local fairs. And I am not in the business of cheating people.”

He moves further along the aisle, displaying his creations, selling a few of the smaller items. “You are free to inspect them with your hands, you don’t need to pay to explore my art.” In a while, an enthusiastic couple buys the ektara without bargaining. Sanjay’s face lights up. “This needed a lot of labour – just listen to its melody.”

'This is not the cheap one that you get at the local fairs. And I am not in the business of cheating people'

Where did you learn this craft, I ask him. “I learnt it on my own. When I missed my exams in Class 8, education was over for me,” 47-year-old Sanjay replies. “For a quarter century I repaired harmoniums. Then I got bored with that work. For the last one-and-a-half years, I have been addicted to this work. Sometimes, when people come with their harmoniums, I do help them, but now this is my occupation. I even create the tools for it with my own hands. You will be amazed to see my handiwork if you come to my house,” he adds, with evident pride in his craft.

Sanjay’s usual train route is between Plassey (or Palashi) and Krishnanagar. “I sell for three days a week and the rest of the days go in making the artefacts. It’s subtle, and cannot be done casually. It took a lot of time to create this wooden bus. You can check it out with your own hands.” He hands me a wooden mini-bus.

How much do you earn? “Today I could sell items worth Rs. 800. The profit margins are very thin. The raw materials come at a high price. I don’t use cheap wood. These require Burma teak, segun or shirish wood. I buy these from wood merchants. I get good quality paint and spirits from Burrabazar or China Bazar in Kolkata. I have not learnt to cheat or trick… I work almost all the time. If you visit my home, you will find me working day and night. I don’t use any machine to polish the wood. I use my own hands. That’s the reason for such finesse.”

Sanjay sells the items he creates for anything between Rs. 40 (for a Shiv-lingam) and Rs. 500 (for a mini-bus). “Tell me, how much will this bus be worth in your shopping malls?” he asks. “Many passengers don’t appreciate this labour of love, they bargain hard. I am barely surviving somehow. Maybe someday they will be able to appreciate my work.”

As the train pulls in to Krsihnanagar, Sanjay gets ready to alight with his basket. He will then go onward to his home in the Ghoshpara basti of Badkulla town in Nadia district. Since he repairs harmoniums and has created such a beautiful ektara , I ask him if he sings too. He smiles and says, “Sometimes, our village songs.”