Gopinath Naikwadi came to Nashik determined to march to Mumbai. “We waited for a year, but the government didn’t meet any of our demands. This time we will not come back till the government implements those demands,” said the 88-year-old farmer from Tambhol village in Akola taluka of Ahmednagar district in Maharashtra.

Naikwadi used to cultivate four acres, of which he owns an acre and the rest is forest department land. But for the past year, he has only been farming on his one acre. “There is no drinking water in the village. How can we farm?” he asked me on the outskirts of Vilholi village in Nashik district, where thousands of farmers had halted for lunch at around 2.30 p.m. on February 21 after marching 10 kilometres for three hours from the Mahamarg bus stand in Nashik. He too had walked there along with around 250 farmers from Akola taluka .

The borewell on their farm went dry a year ago. Now, every six days, a government water tanker supplies drinking water to the village

Every year, Naikwadi and his family cultivated soyabean, bhuimug (groundnut), moong, moth , onion and millet. But the borewell on their farm went dry a year ago. Now, every six days, a government water tanker supplies drinking water to the village. Naikwadi took a crop loan of Rs. 27,000 in 2018 from a village cooperative society. “We grew onions on 20 guntha [half acre]. But all my onions burned because there is no water...” he said. The 88-year-old now worries about repaying the loan. “What can I do?” he asked, anxiously.

Naikwadi walked in the 2018 Long March from Nashik to Mumbai, then went to Delhi in November for the Kisan Mukti Morcha. His wife Bijlabai couldn’t participate in these protests because “she looks after a cow and two goats in the village,” he said. Their son Balasaheb, 42, is a farmer, and two daughters, Vithabai and Janabai, both in their early 50s, are married and homemakers. Two more daughters, Bhagyarathi and Gangubai, passed away.

A decade ago, Gopinath and Bijlabai rolled

beedis

in their village to earn a living. “The contractors used to pay us Rs. 100 for rolling 1,000

beedis.

” This brought them a monthly income of around Rs. 2,000. But, he said that the

beedi

industries in Akola

taluka

shut down around a decade ago because

temburni

leaves were no longer available.

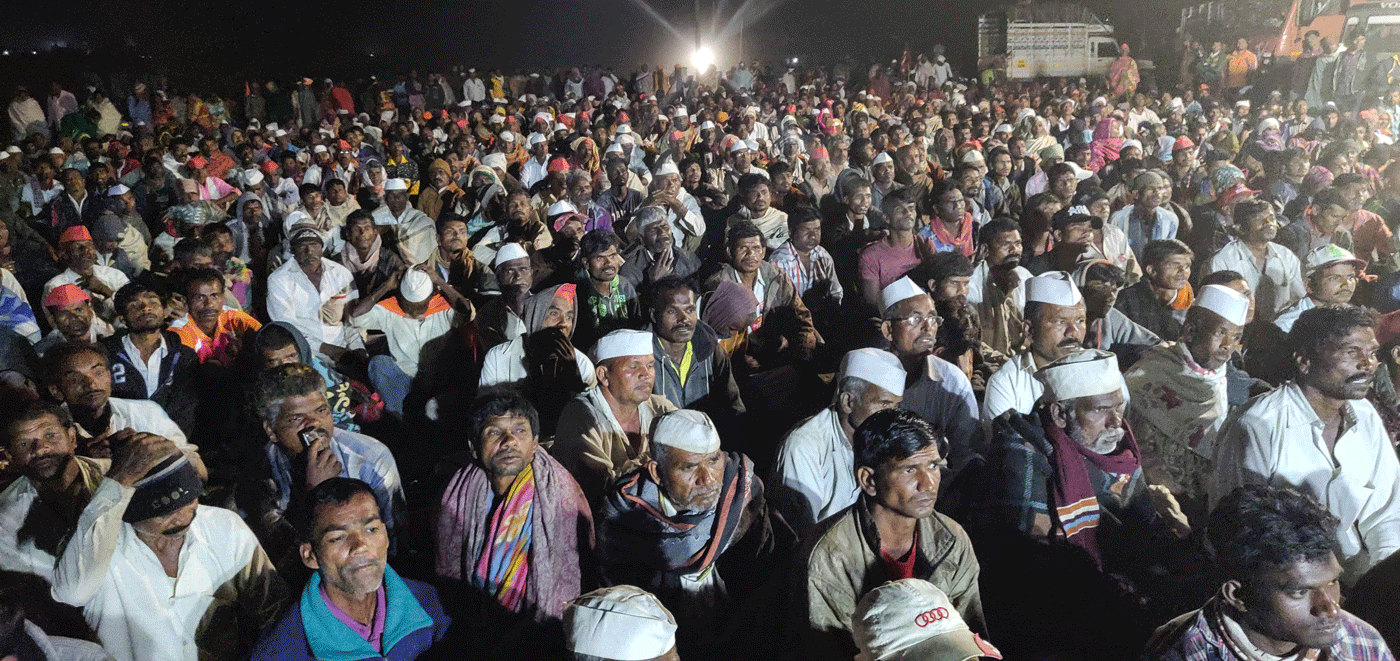

Gopinath Naikwadi was one of thousands of farmers gathered at Nashik to participate in the second Long March to Mumbai

Naikwadi now mainly takes care of the fodder for the family’s animals, and only sometimes does farm work; his son looks after their land. Under the Sanjay Gandhi Niradhar Pension Scheme, he gets Rs. 600 a month. “What can we do with Rs. 600?” he asked. “Our demand is that the pension should be increased to Rs. 3,000.”

“This time, if the government doesn’t implement our demands, we will not leave Mumbai. It’s better to die in Mumbai. Anyway, agriculture in the village is killing us.”

Postscript: Late at night on February 21, the All India Kisan Sabha, the organiser of the march, called off the protest after talks with government representatives that lasted for five hours, and after the government gave a written commitment that it will meet all the demands of the farmers. "We will resolve every single issue in a time-bound manner and we will do a follow-up meeting every two months," Girish Mahajan, state minister for water resources, announced to the gathering. "You [farmers and farm labourers] should not bear the hardship of walking all the way to Mumbai. This is a government that listens. Now we will implement these assurances so that you don't have to take out another march."