- John Dryden in The Spanish Friar (1681)

Rural India — a living journal, a breathing archive

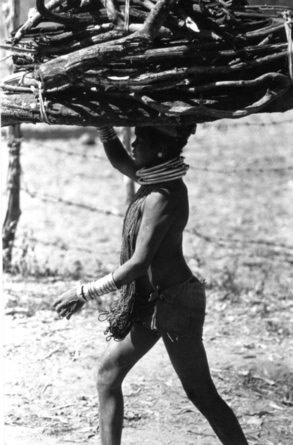

The everyday lives of everyday people

P Sainath

Can a project’s success be judged on the basis of its never being completed? Yes, if it’s a living archive of the world’s most diverse and complex countryside. Rural India is in many ways the most diverse part of the planet. Its 833 million people include distinct societies speaking well over 700 languages, some of them thousands of years old. The People’s Linguistic Survey of India tells us the country as a whole speaks some 780 languages and uses 86 different scripts. But in terms of provision for schooling up to the 7th standard, just four per cent of those 780 are covered.

The Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution lists 22 languages whose development the Union government is obliged to promote. Yet, there are states whose official languages fall outside those 22, like Khasi and Garo of Meghalaya state. Each of six Indian languages is spoken by 50 million people or more. Three are spoken by 80 million or more. One, by close to 500 million. At the other end of the spectrum are unique tribal languages spoken by as few as 4,000 people, some by even less. The eastern state of Odisha alone is home to some 44 tribal languages. The PLSI also reckons close to 220 languages have died in the past 50 years. ‘Saimar’ in Tripura is down its last seven speakers. Most Indian languages have mainly rural speakers.

The same diversity characterises rural Indian occupations, arts and crafts, culture, literature, legend, transportation. As the Indian countryside rushes through an extremely painful transformation, many of these features disappear, leaving us poorer. There are, for instance, probably more schools and styles of weaving in India than in any other single nation. Many of these traditional weaving communities face real collapse, which would rob the world of some of its greatest gifts. Some unique occupations — professional storytellers, epic poem singers — are also in danger of extinction.

Then there are professions known only to a few nations. Like toddy-tappers who climb up to 50 palm trees daily, each one thrice, in season. From the sap they make palm jaggery or a fermented liquor called toddy. In peak season, a toddy tapper climbs a height greater than New York’s Empire State Building — every single day. But so many occupations are in collapse. Potters, metal workers and millions of other highly skilled craftspeople are rapidly losing their livelihoods.

Much of what makes the countryside unique could be gone in 20-30 years. Without any systematic record, visual or oral, to educate us — let alone motivate us — to save this incredible diversity. We are losing worlds and voices within rural India of which future generations will know little or nothing. Even as the present one steadily sheds its own links with those worlds.

This is where PARI comes in

There is surely much in rural India that should die. Much in rural India that is tyrannical, oppressive, regressive and brutal — and which needs to go. Untouchability, feudalism, bonded labour, extreme caste and gender oppression and exploitation, land grab and more. The tragedy, though, is that the nature of the transformation underway more often tends to bolster the regressive and the barbaric, while undermining the best and the diverse. That too, will be captured here. PARI is both a living journal and an archive. It will generate and host reporting on the countryside that is current and contemporary, while also creating a database of already published stories, reports, videos and audios from as many sources as we can. All PARI’s own content comes under the Creative Commons (http://www.ruralindiaonline.org/legal/copyright/) and the site is free to access. Also, anyone can contribute to PARI. Write for us, shoot for us, record for us — your material is welcome so long as it meets the standards of this site and falls within our mandate: the everyday lives of everyday people.

The use of many libraries and museums in India has fallen, more so in the last 20 years. This used to be compensated by the fact that what you could find in our museums, you could also find on our streets: the same miniature painting schools, the same traditions of sculpture. Now those too are fading. Library and museum visits amongst the young are more rare than routine. However, there is one place future generations the world over including Indians will visit more and more. The Net. Internet penetration, particularly broadband, in India is low — but it is expanding. It seems to be the right place to build — as a public resource — a living, breathing journal and an archive aimed at recording people’s lives. The People’s Archive of Rural India. Many worlds, one website. More voices and distinct languages, hopefully, than have ever met on one site.

The use of many libraries and museums in India has fallen, more so in the last 20 years. This used to be compensated by the fact that what you could find in our museums, you could also find on our streets: the same miniature painting schools, the same traditions of sculpture. Now those too are fading. Library and museum visits amongst the young are more rare than routine. However, there is one place future generations the world over including Indians will visit more and more. The Net. Internet penetration, particularly broadband, in India is low — but it is expanding. It seems to be the right place to build — as a public resource — a living, breathing journal and an archive aimed at recording people’s lives. The People’s Archive of Rural India. Many worlds, one website. More voices and distinct languages, hopefully, than have ever met on one site.

It means an undertaking unprecedented in scale and scope, utilising myriad forms of media in audio, visual and text platforms. One where the stories, the work, the activity, the histories are narrated, as far as possible, as far as we can manage, by rural Indians themselves. By tea-pickers amidst the fields. By fishermen out at sea. By women paddy transplanters singing at work or by traditional storytellers. By Khalasi men using centuries-old methods to launch heavy ships to sea without forks and cranes. In short, by everyday people talking about themselves, their labour and their lives — talking to us about a world we mostly fail to see.

PARI hosts and combines video, still photo, audio and text archives. There is content we already have and content we are newly generating. Both will take time and effort to organise and load. The videos generated specifically for PARI record the lives and livelihoods of poor and everyday Indians. For example, a woman agricultural labourer takes you through her life, her work, her labour techniques, family, kitchen, whatever she considers important. Typically the first credit in such a film goes to her; the second to her village / community. The director comes third. PARI respects her ownership of her story. It is also in our mandate to search for ways in which the very people we cover, rural Indians, will also have access to, and a say in, the making of this site. The text collection includes a 'resources' section where we aim to make resident in full text (not just through links) every report / study on or significantly connected to rural India. And, of course, we aim to put up thousands of articles both already published, and exclusively done for, PARI. And the site's 'audiozone' (still under construction) will, over time, hold thousands of clips — conversations, songs, poetry — in every Indian language that we can record. We're also trying to create sub-titling in multiple Indian languages for each documentary generated by us.

PARI: Students, Teachers, Researchers & Education

PARI aims to help create informative and lively educational resources for students, teachers, schools, colleges and universities. Teaching and learning materials including textbooks will increasingly move online in the next few years. That’s a process already on in some parts of the world. Done right, it could mean ‘textbooks’ or teaching material that can be added to, amended, updated or widened. As broadband access grows, it should also mean lower costs for many students, as PARI is a free-access-to-public site. To know more about this and how students can help create their own textbooks, see: http://www.ruralindiaonline.org/about/pari-teachers-students/

And there is also our 'Resources' section where we aim to put up (in full text and not just via links), all official (and unofficial but credible) reports relating to rural India. For instance, every one of the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (NCEUS) reports; those of the Planning Commission and ministries, UN bodies and much more. Researchers will not have to surf multiple sites to access vital reports and studies from different sources.

What will be on PARI? The number of categories you see in the archive are not fixed or final. But a look at just a few of them:

THINGS WE DO: This leads you into the complex world of rural Indian labour. To landless workers in the fields, to farmers and woodcutters, to brick-makers and blacksmiths. From men who push 200 kilograms of coal on bicycles across 40 kilometres to earn a few rupees, to women who scavenge coal at great risk from giant waste dumps. Also migrant labourers who travel thousands of kilometres each year in search of work, never staying anywhere for six months, not even in their own village homes.

THINGS WE DO: This leads you into the complex world of rural Indian labour. To landless workers in the fields, to farmers and woodcutters, to brick-makers and blacksmiths. From men who push 200 kilograms of coal on bicycles across 40 kilometres to earn a few rupees, to women who scavenge coal at great risk from giant waste dumps. Also migrant labourers who travel thousands of kilometres each year in search of work, never staying anywhere for six months, not even in their own village homes.

Apart from covering their stories we will also be shooting the tools and implements that people use — many of those sure to disappear over the next few years.

TONGUES: We hope to — and will try to — record every single Indian language spoken or written that we can possibly record, with the speakers giving us their view of their own language. These recordings could be in audio or video, in little films or ‘talking albums,’ accompanied by text articles.

PHOTOZONE: Tries to archive the best available photographs of every aspect of rural life and livelihoods. The still photo archive starts with a base of 8,000 black and white images of rural Indians, mainly at work and labour, but also with portraits of people, families, homes. A few are up on the site. Most, though, are presently being digitised as they belong to the era of black and white film camera photography (from an array of archival sources). They will be loaded on the site over time. But we also have thousands of digital photographs of rural India (including the only existing, grim record of hundreds of farm households hit by the largest wave of recorded suicides in history). One feature of the still photo archive will be 'talking albums' where the photos on a theme are accompanied by 'audio captions' from the photographers.

GETTING HERE: On the diversity of modes of transportation. Including the peculiarly Indian contraption called ‘jugaad,’ a country-made ‘automobile’ (running on a five-HP motor) that cannibalises discarded parts from various vehicles and which can have wheels of different sizes. And also bullock carts, horse carts, donkeys, camel carts and camels as transportation in themselves.

GETTING HERE: On the diversity of modes of transportation. Including the peculiarly Indian contraption called ‘jugaad,’ a country-made ‘automobile’ (running on a five-HP motor) that cannibalises discarded parts from various vehicles and which can have wheels of different sizes. And also bullock carts, horse carts, donkeys, camel carts and camels as transportation in themselves.

WE ARE: About communities and cultures. Covering distinct communities, groups and cultures and their stories. Their drama and theatre, song and dance, poems, stories and legends.

THINGS WE MAKE: On arts and crafts and artists and crafts-persons. The countless schools and skills and traditions and their products.

FOOTSOLDIERS OF FREEDOM: The last living freedom fighters of rural India, most now in their 90s. People who spent many years in prison fighting for India’s freedom from colonial rule and the establishment of an independent, democratic Indian nation. In the next decade there will be none left to tell the tale.

FARM CRISIS: A chronicling in words, videos, still photographs and audio recordings, the story of India’s greatest and on-going agrarian crisis. But which also catalogues all other aspects of agriculture, recognising that farming’s crisis goes far beyond the suicides

FARM CRISIS: A chronicling in words, videos, still photographs and audio recordings, the story of India’s greatest and on-going agrarian crisis. But which also catalogues all other aspects of agriculture, recognising that farming’s crisis goes far beyond the suicides

MUSAFIR: A rolling notebook, with posts by writers journeying in different parts of rural India, recording their experiences.

We will also include livestock and wildlife — and many other categories, brick by brick. While we constantly try to build and expand a contributor gene pool, there will be editorial selection and quality control. The use of experienced contributors with a credible record is important to this work, of course. Most of these will be journalists, writers and authors. But not all. Any interested Indian can participate, write for us, or shoot even on cell phones with decent video quality, if the material falls within the mandate of the archive. You don’t need to be a professional journalist. You might even have skills or expertise in another field that we could utilise for the archive — as a techie, or researcher, or designer or translator or editor / video editor, volunteer. Remember the narratives that make up the overwhelming share of the material comes from rural Indians themselves, not from the professional media persons who help record their story. Some of those rural Indians are going to be shooting their own stories. And the stories will be renewed and reported — as long as there is a countryside.

Public access to PARI is free. The site is run by The CounterMedia Trust. A more informal body, the CounterMedia Network, supports and funds the Trust and its primary activity through membership fees, volunteer work, donations, and direct personal contributions. This voluntary network of reporters, professional filmmakers, film editors, photographers, documentary makers, television, online and print journalists, represents PARI's biggest asset. Besides, academics, teachers, researchers, techies and professionals from many other fields have also donated their expertise free of charge to establish the entity and design the site. PARI will need money to create content beyond what we can get done free, and will aim at crowdsourcing for that. Rural India can never be fully 'captured' and the content up on this site consists of fragments of many giant realities. We can expand our coverage of those many worlds only with the widest possible public participation.