The windows of the local post office creak open, and the postman himself looks out through the window seeing us approach.

Renuka beckons us in with a smile into the post office – housed in a room, with a door leading to it from the foyer of the house. The smell of paper and ink greets us as we step into his small working space. He is stacking away what is the last post for the day. Smiling, he gestures for me to sit. “Come, come! Please make yourself comfortable.”

In contrast to the weather outside, the inside of the postman’s office and home is cool. The lone window is open to coax in the breeze. Multiple handmade posters, maps and lists hang on the whitewashed walls. The small room is tidy and organised, as one would expect such an important place to be. A desk and some shelving area take up most of the room, but it doesn’t feel cramped.

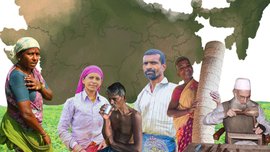

The 64-year-old Renukappa is a Gramin Dak Sevak (Rural Postal Service) in Deverayapatna town in Tumkur district; and six villages fall in his jurisdiction.

The official timings for this rural post office in Deverayapatna are 8:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., but Renuka Prasad, its only employee, often starts working at 7 a.m. and continues till 5 in the evening. “Four and a half hours is not enough to complete my work,” explains the postman.

Renuka at work as a Gramin Dak Sevak (Rural Postal Service) in his office in Deverayapatna town in Tumkur district; and six villages fall in his jurisdiction

The postman’s work starts with the postal bag of letters, magazines and documents that arrive in the morning from nearby Belagumba village in Tumkur taluk. He must first register all the mail and then he sets out to deliver them by around 2 p.m. everyday. The six villages he delivers to – Deverayapatna, Maranayakapalya, Prashantanagara, Kunduru, Bandepalya, Shreenagara – lie within a six kilometre radius. He lives with his wife Renukamba; his three grown-up daughters have moved out.

He shows us a small handmade map hung above his desk with all the villages he needs to visit, how far they are, labelled with the four compass points in Kannada, and complete with a legend. The closest village is Maranayakapalya which is 2 kilometres to the east. The other villages are Prashantanagara, around 2.5 km to the west, Kunduru and Bandepalya lie 3 km to the north and south respectively, and Shreenagara lies 5 km away.

Renukappa is the lone postman who is out in the sun or pouring rain; the postman who always delivers.

To traverse these long distances he has an ageing bicycle – like the stereotypical postman in stories – riding into the village on his bike and cheerfully greeting people who run to welcome him.

“Renukappa, we have a pooja at our house today. Do come!” a lady walking by in front of his house calls out to him. He beams at her and nods. Another villager passes by waves to him and shouts a greeting. Renukappa smiles and waves in return. The warm relationship between the villagers and their postman is evident.

Renuka travels on his bicycle (left) delivering post. He refers to a hand drawn map of the villages above his desk (right)

The postman covers 10 km on an average day, delivering post. Before retiring for the day, he must note and account everything he has delivered in a thick, worn-out notebook.

Renukappa says the development of online communication has led to a fall in the number of letters, “but magazines, bank documents etc. have doubled in the past few years, and so my work has only increased.”

Gramin Dak Sevaks like him are deemed ‘extra departmental workers’ and are not considered for emoluments, let alone pension. They are involved in all functions, such as the sale of stamps and stationery, the transport and delivery of mail and any other postal duties. Since they are part of the regular civil service, they are not covered by Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules,2021 . Currently, the government has no proposal to grant any pensionary benefits to them, other than the Service Discharge Benefit Scheme, effective from 01/04/2011.

After Renukappa retires, his monthly salary of Rs. 20,000 a month will stop and he will not receive a pension. “Postmen like me, we waited for so many years, hopeful that some change would happen. We waited for someone to acknowledge our hard work. Even if we receive just a small portion of what all those other pension recipients are given, say a thousand rupees or two, then that would be more than enough,” he says. “I will have retired by the time this changes,” he adds wistfully.

Renuka covers 10 km on an average day, delivering post

Renuka's stamp collection, which he collected from newspapers as a hobby

His mood lifts when I ask him about a poster with small cuttings, laminated and displayed on the wall. “That poster is a small joy for me. I call it the anchechiti (ಅಂಚೆಚೀಟಿ/stamp) poster,” he says.

“This has become a hobby for me. A couple of years ago the newspaper started releasing these stamps in the newspaper to honour famous poets, freedom fighters as well as other notable figures.” So Renuka started collecting them as soon as they came out – cutting them out of the newspaper. “It felt nice to wait for the next one to come out.”

We would like to thank Shwetha Satyanarayan, teacher at TVS Academy, Tumkur for her help in coordinating this piece. PARI Education worked with the following students as part of this project: Aastha R. Shetty, Druthi U., Divyashree S., Khushi S. Jain, Neha J., Pranith S. Hulukadi, Hani Manjunath, Pranathi S., Pranjala P. L., Samhitha E. B., Parinitha Kalmath, Nirutha M. Sujal, Gunotham Prabhu, Aditya R. Haritsa, Utsav. K. S.