Five days, 200 kilometres and Rs. 27,000 – it sums up Ravi Bobde’s desperate search for the remdesivir injection in Maharashtra’s Beed district.

It all began after his parents developed signs of Covid-19 in the last week of April this year. “They started coughing heavily, and had breathing difficulties and chest pains,” Ravi, 25, recollects while walking through his seven-acre farmland in Beed’s Harki Nimgaon village. “So I took them to a nearby private hospital.”

The doctor immediately prescribed remdesivir – an antiviral drug used to treat Covid-19 – which had been in short supply in Beed. “I ran around for five days,” says Ravi. “I was out of time and I didn’t know what to do. So I hired an ambulance and transferred my parents to a hospital in Solapur.” He was anxious throughout the journey. “I will never forget those four hours in the ambulance.”

The ambulance driver charged Rs. 27,000 to take his parents – Arjun, 55, and Geeta,48 – to Solapur city, nearly 200 kilometres from their village, located in Majalgaon taluka . “I have a distant relative who is a doctor in Solapur,” explains Ravi. “He told me he would arrange the injection. People all over Beed were struggling to get their hands on the drug.”

Remdesivir, which was originally developed for the treatment of Ebola, was found to be effective on hospitalised Covid-19 patients early in the pandemic. In November 2020, however, the World Health Organisation issued a “ conditional recommendation ” against the use of remdesivir. There was no evidence, said the WHO, that the drug improved survival and other outcomes, in hospitalised Covid-19 patients, regardless of disease severity.

But while the antiviral drug may not be included in the treatment guidelines anymore, it isn’t banned, says Dr. Avinash Bhondwe, former president of Indian Medical Association’s Maharashtra chapter. “Remdesivir was used to tackle the previous coronavirus infection [SARS-CoV-1], and was found to be effective, which is why we started using it when the new coronavirus disease [SARS-CoV-2 or Covid-19] first broke out in India.”

The farm in Harki Nimgaon village, where Ravi Bobde (right) cultivated cotton, soyabean and tur with his late father

A course of the medicine includes six injections over a five-day period. “If used in the early days of the [Covid-19] infection, remdesivir stalls the growth of the virus in the body and can be effective,” Dr. Bhondwe explains.

However, when infection sets in, Covid patients in Beed have hardly had access to remdesivir because of the red tape and shortage of the drug. The district receives its supply from the state government and a private firm called Priya Agency. “When a doctor prescribes remdesivir, the patient’s relatives have to fill up a form and submit it to the district administration,” says Radhakrishna Pawar, the district health officer. “Depending on the supply, the administration makes a list and provides remdesivir to the concerned patients. There was a shortfall during the months of April and May.”

Data provided by Beed’s district magistrate, Ravindra Jagtap, shows that there was a vast difference in the demand and supply of remdesivir. Between April 23 and May 12 this year – at the peak of the second Covid wave in the country – 38,000 remdesivir injections were needed in the district. However, only 5,720 were made available, which was about 15 per cent of the requirement.

The shortage generated a large-scale black market of remdesivir in Beed. The price of the injection, capped at Rs. 1,400 per vial by the state government, went up to as high as Rs. 50,000 on the black market – making it over 35 times more expensive.

Sunita Magar, a farmer with four acres of farmland in Beed taluka 's Pandharyachiwadi village, paid a little less than that. When her 40-year-old husband, Bharat, caught Covid-19 in the third week of April, Sunita paid Rs. 25,000 for a vial of remdesivir. But she needed six vials, and was legally able to procure only one. “I spent Rs. 1.25 lakhs only on the injection,” she says.

Sunita Magar and her home in Pandharyachiwadi village. She borrowed money to buy remdesivir vials from the black market for her husband's treatment

When Sunita, 37, submitted her requirement of vials to the administration, she was told she would be informed when it became available. “We waited for 3-4 days but there was still no stock. We couldn’t wait forever,” she says. “The patient needs treatment on time. So we did what we had to.”

After losing time on the search for remdesivir and then finding it on the black market, Bharat died in hospital two weeks later. “I have borrowed money from relatives and friends,” says Sunita. “About 10 of them chipped in with Rs. 10,000 each to help me out. I lost money and also lost my husband. People like us don’t even have access to medicines. You can save your loved ones only if you are rich and connected.”

The search for remdesivir has wrecked many families like Sunita’s in Beed. “My son will have to help me in our farm while he continues his education,” she says, adding that to repay her debt, she would have to work in others’ farms as well. “It is like our life has turned upside down in just a few days. I don’t know what to do. There are not many work opportunities here.”

Unemployment and poverty have driven farmers and farm workers from Beed to migrate in large numbers to the cities to find work. The district, which has recorded over 94,000 Covid cases and 2,500 deaths so far, is in Marathwada region, which accounts for the highest number of farmers’ deaths by suicide in Maharashtra. Already grappling with climate change, water scarcity and debt due to agrarian distress, people in the district have been compelled to borrow more money to illegally procure remdesivir, pushing them deeper into debt.

Illegal trade of remdesivir is the result of the state government’s lack of foresight, says Dr. Bhondwe. “We could see the rise in Covid-19 infections during the second wave. In April, about 60,000 cases were being diagnosed daily [in the state].”

Left: Sunita says that from now on her young son will have to help her with farm work. Right: Ravi has taken on his father's share of the work at the farm

On an average, 10 per cent of Covid-positive patients need hospitalisation, the doctor says. “Of them, 5-7 per cent would need remdesivir.” The authorities should have estimated the requirement and stocked up on the drug, adds Dr. Bhondwe. “Black marketing happens when there is a shortage. You would never find Crocin being sold on the black market.”

Sunita doesn’t divulge anything about who supplied her with the remdesivir vials. She says: “He helped me in my time of need. I will not betray him.”

A doctor at a private hospital in Majalgaon, who does not wish to be named, hints at how the drug could have gone on the black market: “The administration has a list of patients who have asked for the injection. In several cases, it takes over a week for the medication to arrive. During that period, the patient either recovers or dies. So the relatives don’t follow up. Where does that injection go?”

However, District Magistrate Jagtap says he is not aware of any large-scale black marketing of the drug in Beed.

Balaji Margude, a journalist of the Dainik Karyarambh newspaper in Beed city, says that most of those who illegally procure remdesivir get it through political connections. “Local leaders across party lines, or the people connected to them, get access to it,” he says. “Almost everyone I have spoken to has said this, but they won’t give further details because they are scared. People have borrowed money they can’t repay. They have sold their land and jewellery. Many patients have died while waiting for remdesivir.”

Remdesivir is effective in the early stages of the coronavirus infection before a patient’s blood oxygen level drops, Dr Bhondwe explains. “It doesn’t work in several cases in India because patients mostly come to a hospital only when they are critical.”

It was probably what happened with Ravi Bobde’s parents too.

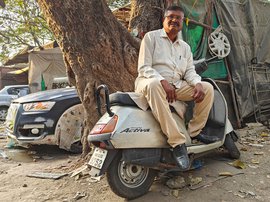

Ravi is trying to get used to his parents' absence

The shortage of remdesivir generated a large-scale black market in Beed. The price of the injection, capped at Rs. 1,400 per vial by the state government, went up to as high as Rs. 50,000 on the black market

After the ambulance took them to the hospital in Solapur, Arjun and Geeta Bobde died within the span of a week. “The four-hour journey worsened their condition. The roads are not great, so it must have been taxing on them,” says Ravi. “But I couldn’t think of another option. I waited for five days to get remdesivir in Beed.”

With his parents gone, Ravi is now alone at home in Harki Nimgaon. His elder brother, Jalindar, lives and works in Jalna, about 120 kilometres away. “I feel strange,” says Ravi. “My brother will come and stay with me for a while but he has a job. He will have to go back to Jalna and I will have to get used to staying alone.”

Ravi used to help his father cultivate their farmland, where they grew cotton, soyabean and tur . “He did most of the work, I only helped him out,” says Ravi, sitting shrivelled on his bed at home. His eyes betray the anxiety of someone on whom too many responsibilities have been thrust too soon. “My father was the leader. I followed him.”

On the farm, Arjun would focus on work that required more skill, like sowing, while Ravi performed the labour-intensive tasks. But during this year’s sowing season, which started around mid-June, Ravi had to take up his father’s load as well. It was an intimidating start to the farming season for him – he didn’t have a leader to follow.

Looking back, five days, 200 kilometres and Rs. 27,000 don’t even begin to sum up what Ravi lost in his desperate search for remdesivir.