On February 15, 1885, Mukta Salve, a Dalit student in the school started by Mahatma Jotirao Phule, wrote an essay titled ‘ Mang-Maharanchya Dukkhavishayi ’ (‘About the grief of Mang and Mahars’). It was published in Dnyanoday , a Marathi fortnightly magazine. She challenged the custodians of religion in this fiery essay : “Let that religion, where only one person is privileged, and the rest deprived, vanish from the earth and let it never enter our minds to boast of such a [discriminatory] religion.”

Mukta Salve was just 15 when she wrote about her own Mang people. Her evocative piece tells us how the Brahmin rulers and all of society tortured the Dalits. Like her, Kadubai Kharat challenged the spiritual leaders at Alandi and defeated them in a debate on spirituality and religion. Kadubai sings about sorrow and struggles of the common people. Her songs convey deep meanings and philosophies. They explain the value of equality and also express her gratitude to Babasaheb Ambedkar.

*****

काखेत पोरगं हातात झाडनं डोईवर शेणाची पाटी

कपडा न लत्ता, आरे, खरकटं भत्ता

फजिती होती माय मोठी

माया भीमानं, भीमानं माय सोन्यानं भरली ओटी

मुडक्या झोपडीले होती माय मुडकी ताटी

फाटक्या लुगड्याले होत्या माय सतरा गाठी

पोरगं झालं सायब अन सुना झाल्या सायबीनी

सांगतात ज्ञानाच्या गोष्टी

सांगू सांगू मी केले, केले माय भलते कष्ट

नव्हतं मिळत वं खरकटं आणि उष्टं

असाच घास दिला भीमानं

झकास वाटी ताटी होता

तवा सारंग चा मुळीच पत्ता नव्हता

पूर्वीच्या काळात असंच होतं

बात मायी नाय वं खोटी

माया भीमानं, मया बापानं,

माया भीमानं माय, सोन्यानं भरली ओटी

Child on an arm, broom in my hand,

A basket of cow dung on my head

Rags my adornment, leftover morsels my wage,

Believe me, life was a huge disgrace

My Bhim, yes, my Bhim, he filled my life with gold

My broken hut had a broken door

The torn saree had more knots than one can count

Now my child is an officer, my daughters-in-law too

How they tell me words of wisdom

I suffered such hardships and worked very hard

Not even leftovers or half-eaten morsels for meals

But Bhim came and fed us

From a superb plate and bowl

Poet Sarang was not on the scene

This is how we lived in those days

I am not telling lies, my dear

My Bhim, my father, he filled my life with gold

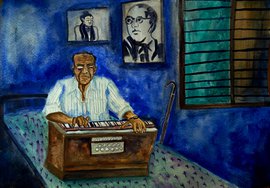

Kadubai Kharat and her

ektari

at Dr. Ambedkar Memorial Lecture held at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Tuljapur, a few years ago

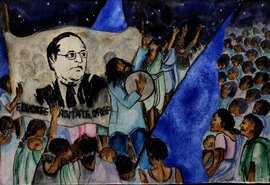

We have heard thousands of songs written and sung to express gratitude towards Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. But only a few are close to our heart and have become so popular that they are a part of our collective memory. This song by Kadubai Kharat has attained that stature. It is highly popular among the people, having entered their homes and hearts – and it remains one of the most famous household songs on Ambedkar.

There are many reasons why the song became such a hit. Perfect words for the emotion, clear voicing, unique sounds and instruments, and the special bass voice of Kadubai Kharat. A simple person, she came into prominence on TV shows like Jalsa Maharashtracha on Colors channel, and on Zee TV. But we know little about the dark journey she had to undertake to get there. Kadubai's life is full of such experiences like her name signifies. ( Kadu , which means bitter in Marathi, is a popular given name for girls in Marathwada, believed to ward off the ‘evil eye’.)

Kadubai’s father was Tukaram Kamble...

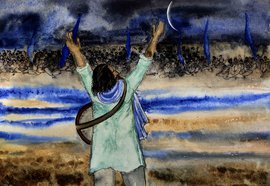

Living in poverty since her childhood, Kadubai lost her husband to a heart attack within a couple of years of getting married at only 16. The responsibilities of life and of their three children – two boys and a girl – it all fell upon her. She went door to door with her father’s ektari , singing traditional bhajan-kirtan [devotional songs]. In Vedic times, Gargi and Maitreyi, the vidushi s [learned women], had debated with the gatekeepers of religion. Similarly, Kadubai had once argued with custodians of spirituality in the courtyard of Alandi temple. She spent many years performing a variety of devotional songs, but it was barely enough to bring two meals a day. So she decided to leave her village in Jalna district [Maharashtra] and move to Aurangabad.

Kadubai built a small tin hut on gairan land near the Aurangabad-Beed bypass road. A Buddhist now, she says she faced the world supported by the love, compassion, inspiration and energy of Babasaheb

But where could she live in Aurangabad? She built a small hut in a

gairan

land [government-owned grazing ground] near the Aurangabad-Beed bypass road and started living there without civic amenities such as water or electricity. She lives there even today. For some time in the beginning, Meera Umap took Kadubai into her performance troupe. But the money was not enough to take care of three children. Kadubai says, “It was rainy season and we had not seen any sun almost for a week. I could not even go out of the house for any work. All the three children were struggling with hunger. I went door to door and sang

bhajans

. One woman said, ‘Sing songs on Dr. Ambedkar’. I sang a song and also told her about my children’s hunger. She went into her kitchen and brought out the provisions she had bought for her own household, which was enough to last me a month. She understood my children’s hunger.

“Ambedkar’s song put food in their bellies. My whole life changed. I gave up

bhajan-kirtan

and started following the path shown by Dr. Ambedkar. Determined to walk on that path, in 2016 I gave up Hinduism and left my Matang caste. I adopted Buddha’s

dhamma

[Buddhism]!”

Kadubai lost her husband and her father, too. But, through all her struggles, she had the ektari and her melodious voice always. She did not fall apart after the death of her father and husband.

Two things accompanied Kadubai in her struggle for survival: ektari and her voice. She faced the world supported by the love, compassion, inspiration and energy of Babasaheb.

Her journey, going door-to-door and singing and seeking alms, to becoming a celebrity in Maharashtra today, is nothing short of remarkable. The ektari has been her companion for more than 30 years.

*****

The earliest reference to ektari can be found in cave number 17 of Ajanta Caves [in Aurangabad district, Maharashtra]. There is a painting of the instrument on the cave walls. In Maharashtra, each caste group has a preferred instrument. These instruments are played for ritual and cultural purposes. Halgi is played by the Mang; kingri by Dakkalwar; gaji dhol by the Dhangar; chaundak by goddess Yallama’s followers; davru by the Gosawi; and dholki and tuntune by the Mahar community.

Dr. Narayan Bhosale, a professor of history at University of Mumbai, says that the Gosavi community is known as Davru-Goswami because of its tradition of playing the davru instrument. The Bhat community who sing bhajans about matriarchy are bards. They play the tuntune and sambal .

Ektari and tuntune are similar in form. But their sound, the way they are played, and the process of making each instrument is different. The Mahar and Mang tradition of singing bhajans with ektari is not seen in the upper castes – or it’s rare. The instruments are an integral part of the cultural life of these communities. These are played during social and religious events and on different occasions in daily life.

About the ektari , the popular shahir Sambhaji Bhagat says: “Its sound and notes are closely linked to sorrow. The sound, ‘ ding nag, ding nag …’ conveys pain. The notes are from Bhairavi, a raga of the Indian classical music tradition, which expresses grief. You feel all of Bhairavi when you listen to the ektari . Almost all the bhajans sung with the ektari are composed in Bhairavi. It starts and ends with Bhairavi.”

The Bhakti tradition of Hinduism has two branches: sagun [where the deity has a form] and nirgun [where the deity has no tangible form]. The idol of the deity and the temple are central to the sagun tradition. But, for nirgun , there is no place for a temple or idol. The followers of path sing bhajan . To them, music is worship, and they take it to the people and worship their god or goddess. Before converting to Buddhism, the Mahar people in Maharashtra were followers of Kabir and Dhagoji-Meghoji.

आकाश पांघरुनी

जग शांत झोपलेले

घेऊन एकतारी

गातो कबीर दोहे

The world is asleep

With the ektari

Kabir sings his dohe [couplets]

All of Kabir’s

bhajans

came to be played on the

ektari

. His labour and life experiences, philosophy, and worldview can be found in these songs.

Kabir is a spiritual and musical inspiration to the oppressed and marginalised people. Nomadic communities and itinerant singers, with ektari in hand, have spread his message throughout the country. Purushottam Agrawal, a Kabir scholar, says that Kabir’s influence was not limited to the Hindi-speaking regions and Punjab. He had reached Odia and Telugu speaking areas, and also Gujarat and Maharashtra.

Before 1956, Mahar and other castes that were considered ‘untouchable’ in Maharashtra and also across its borders, in Andhra, Karnataka, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, were all followers of Kabir. They were Kabirpanthi. Tukaram, the learned saint of Maharashtra, was influenced by Kabir too. It is believed that the influence of Kabir and the Kabirpanthi tradition brought the ektari to these communities.

Dalit families, especially the Mahar and other historically untouchable communities, follow the practice of singing with ektari . The instrument is in use even today. They sing bhajans on the ektari when there is a death in the family. The Mahar community sang bhajans explaining the tenets of Kabir’s philosophy. Fruitfulness of life, its expression, importance of good deeds and the certainty of death form the basis of Kabir’s worldview, which he explained through his dohe (couplets) and bhajans . Kadubai knows hundreds of songs that belong to the Kabir, Nath and Warkari sects [of the Bhakti era].

Kadubai sings Kabir’s ‘

Gagan mein aag lagi hain bhari

'

(‘A wild and intense fire has broken out in the sky')

.

And an

abhang

by Tukaram:

करीन नामाचा या गजर

धन चोरला दिसत नाही

डोळे असून ही शोधत राही

I will chant your name!

A thief cannot see it

Though with sight, keeps searching for it

Though many like Kadubai sang such compositions, they moved to singing other songs due to the growing influence of Dr. Ambedkar’s social justice movement.

Prahlad Sinh Tipania, a renowned singer from Madhya Pradesh who has taken Kabir’s bhajans to different places with the ektari , belongs to the Balai caste group. The community’s status is similar to the Mahar in Maharashtra. Balais are settled in Burhanpur, Malwa and Khandwa regions of Madhya Pradesh, and on the Maharashtra border. When Dr. Ambedkar elaborated at length the caste atrocities faced by Dalits, he had cited examples of the Balai community. If we examine the revenue records of villages, we find that around a hundred years ago, the Mahars were employed by the village to guard the residents, assist in measuring the land, and carry death notices to relatives. This was their role in society. In Madhya Pradesh, the same tasks were assigned to the Balai community – the village guard used to be called a Balai. The same caste was named Mahar during the British period. How did this transformation happen? The British administration in Khandwa and Burhanpur had observed that the Balai in Madhya Pradesh and the Mahar in Maharashtra were similar – their way of life, customs, social practices and work were also similar. And so, those belonging to the Mahar caste were declared as Balai in Madhya Pradesh. Their caste was recorded as Mahar again, on paper, in 1942-43. This is the story of the Balais.*****

Kadubai has become a celebrity in Maharashtra today. The

ektari

has been her companion for more than 30 years

Prahlad Sinh Tipania and Shabnam Virmani [of the Kabir Project ] sing with the ektari when they sing Kabir bhajans .

The ektari instrument is seen in many parts of the country – with bhajan singers and travelling artistes. About 100-120 centimetres long, ektari has many names. In Karnataka, it is called eknad ; in Punjab, tumbi ; baul in Bengal; and tati in Nagaland. It is called burra veena in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. Adivasis in Chhattisgarh use the ektari in their music and dance.

A flattened, gouged-out and dried pumpkin is used as the resonater in an ektari . A piece of leather covers the resonator’s narrow mouth. A hollow velu [a type of bamboo] is inserted in the resonator. The lower end comes out of the gourd and a string is attached. The string is put on the bridge and tied to a peg at the other end of the velu . The string is plucked with the index or middle finger.

The design and process of making an ektari [one-string drone lute] is simpler than that of other string instruments. Pumpkin, wood, bamboo and string are easily available. The pumpkin is considered to be the best resonator. It is widely used in African instruments as well. Ektari provides a base note and also the basic rhythm. The singer can tune their voice, and pace the song to the sound. It is an ancient, indigenous instrument. Initially, the string was also made of leather, from the inner lining of animal hide. In Karnataka, ektari with leather strings is still played in Yallamma’s worship. It is called zumbaruk . So we can say that the first-ever note and first-ever rhythm was created when a leather string resonated against a leather disc. And there it was, the first musical instrument. Metal strings were used after metal was invented in agrarian society. All over the world, many one-string instruments were invented and played. The instruments created and played by street musicians and nomads were also closely linked to their way of life.

It is believed that the ektari was widely used by the saints and poets of the Bhakti movement in India. But, historically, this is not strictly true. We find that Kabir, Mirabai and some Sufi saints used the ektari while singing, but in Maharashtra, many poet-saints, from Namdev to Tukaram have used taal (cymbals), chipli (a wooden clapper with metal plates) and mrudang (a hand drum). In many drawings and images, the saints are shown carrying a veena in their hands.

The Marathi Vishwakosh says: “ Veena is an ancient string instrument used in Indian music. It was used to count the notes while reciting Vedic chants.” Though we see it in the images of saints such as Namdev and Tukaram, we do not find its reference in any abhang written by Tukaram. But we find several references of the other instruments: taal, chipli and mrudang .

We could say that the image of Tukaram holding a veena is a Brahminical representation of the saint.

The aspects that form a part of people’s daily lives has always been appropriated by Brahminical thought. Deities, cultural practices, and other sensibilities of the masses have been claimed under Brahminical tradition, changing their original nature and character. As British conquered and took over the Indian land, the Brahminical order lost its power after the fall of the Peshwas. To compensate for that loss of position in society, Brahmins established their rule in the cultural sphere. And, in that process, many art forms and musical instruments that belonged to the labouring classes were appropriated by the emerging cultural power-centres.

The working class lost its ownership and rightful control over these arts and instruments, and eventually, the very people who created them were dislodged from the spheres of art and music.

Mrudang , a hand drum used in the Warkari tradition is a Dravidian instrument made from leather, and produced by the untouchables in south India. Veena , on the other hand belongs to the Bhagwat tradition, followed more in north India. It is possible that these groups introduced the veena to the Warkari sect. The ektari , sambal , timki , tuntune and kingri are instruments created by the deprived and oppressed communities of India. While the veena , santoor and sarangi – the instruments used in classical music – originated in Persia and came to India via the Silk Route. The most renowned veena artists are in Pakistan, and the tradition of Indian classical music is in safe hands there. Quetta in Pakistan has many artists who make instruments such as veena and santoor , used mainly in Brahminical classical music. In India, Muslim artisans in Kanpur, Ajmer and Miraj make them.

The oppressed and marginalised communities in our country originally produced leather instruments and several string instruments. These were their cultural alternatives to the Brahminical traditions of music and art. Brahmins used classical music and dance to rule cultural life.

*****

Kadubai’s songs played with the ektari sound beautiful. The instrument brings out the clarity and emotional depth of her singing.

‘Come, listen to this story,’ is how Ambedkari shahirs like Vilas Ghogare, Prahlad Shinde, Vishnu Shinde and Kadubai Kharat have toured the streets and gone door-to-door, singing Ambedkari songs on their ektari . An instrument of nomadic people all over the world, the ektari is always on the move.

Just as ektari has been an integral part of the musical world of the untouchables, it is also a very important tool in their spiritual evolution. As science developed and new instruments were introduced, folk traditions and folk instruments were replaced – like the ektari . Kadubai may well be the last artiste to perform with the ektari in her hand. In recent times, the use of Brahminical and modern music has increased among Ambedkari singers, abandoning the ektari .

New songs on Ambedkar are being set to the tunes of popular Marathi songs such as ‘ Waat maajhi baghtoy rickshawala ’ [‘The rickshawala is waiting for me’]. It is not that modern music or instruments should not be used, but does your style match the instrument? Does the message get across? Is it reaching the people? Does it convey the meaning of what is being sung? These are the real questions. Modern instruments are created in human society, and they should be used to develop our music. But Ambedkari songs are being set to filmy tunes. They are loud, noisy and harsh on the ears. They have become hoarse. There is no deep philosophy of Ambedkar in the songs apart from fandom and assertion of identity. Experimentation without consciousness and an understanding of the philosophy will only get people to dance. They don’t last long, don’t reach the people, and don’t become a part of people’s collective memory.

In Kadubai’s voice is the voice against thousands of years of slavery. She is a people’s singer who has risen out of extreme poverty and adversity. Her songs make us realise about caste and religion, and the cruelty and inhumanity of untouchability and slavery. In her ektari , she carries the rich legacy of her family and community. Her ektari songs touch our hearts.

मह्या भिमाने माय सोन्याने भरली ओटी

किंवा

माझ्या भीमाच्या नावाचं

कुंकू लावील रमाने

अशी मधुर, मंजुळ वाणी

माझ्या रमाईची कहाणी

My Bhim filled my life with gold

Or

In my Bhim’s name

Rama applied the

kunku

[vermillion]

Such a sweet and melodious voice

This is the story of my Ramai

Through this song, a common person can easily understand Ambedkar’s philosophy. It expresses gratitude to Ambedkar, the daily struggles and sufferings of life, deep spirituality... also a deeper understanding of life. Only a few have wandered and struggled against the system using their voice. On the one hand they resist the social order, and on the other, the memory of our history is kept alive by their voices and instruments. Kadubai is one of them.

This story was originally written in Marathi.

The multimedia feature is part of a collection titled ‘Influential Shahirs, Narratives from Marathwada’, a project implemented by India Foundation for the Arts under their Archives and Museums Programme in collaboration with People’s Archive of Rural India. This has been made possible with part support from Goethe-Institut/Max Muller Bhavan New Delhi.