All the handloom halls

Into mortuary rooms

Being metamorphosed

That inexplicable sorrow!

(From ‘Maggam bathuku’, an epic poem by Dr. U. Radheya, who is from a family of weavers; translated by Dr. P. Ramesh Narayana)

In another age, Shankara Dhanunjaya's passion for weaving silk sarees and his mastery of different kinds of handlooms would have won him respect, stature and even a decent living.

But Dhanunjaya was born in 1981, and when he was 18 the handloom industry was already on a slow downward slide. And by the time he was 35 in 2016, growing debts and crumbling dreams amid crippling policy changes drove him to kill himself.

Dhanunjaya’s wife S .Chandrakala, his mother Venkatalakshmi, and his daughters Vijaya Lakshmi and Janayethri

Dhanunjaya was born in Dharmavaram town of Anantapur district in Andhra Pradesh. The town was known for its pattu cheera (silk sarees) even during the 19th century. It attracted migrants who came to settle here as weavers. Among them were Dhanunjaya’s parents, Shankara Venkatappa and Shankara Venkatalakshmi, who quit agricultural labour in Marala village of Anantapur and moved to Dharmavaram.

In Dhanunjaya’s childhood, weaving was one of the most sought-after occupations. “Weavers would be asked to sit in the front row during all the functions and festivals,” Pola Ramanjaneyulu, a weaver from Dharmavaram, recalls. Ramanjaneyulu, 64, is the president of the Andhra Pradesh Chenetha Karmika Sangham, a weavers’ association. “People from all the other castes respected us because we taught weaving to everyone.”

Weavers were regarded as artists, and formal schooling was secondary. "There was no question of studying,” says Gaddam Chowdamma, Dhanunjaya’s mother-in-law, a retired weaver. “We used to study very little. Just enough to learn to procure silk for the handloom or to be able to help the master-weaver with the accounts.”

Dhanunjaya dropped out of school during Class 7 to learn weaving. With a natural talent for the craft, he was a fast learner. But by then the handloom sector had been in decline for a decade.

Till the early 1980s, the Ministry of Industry and Commerce looked after handlooms as a separate and priority sector. Strict laws applied, and powerlooms were heavily regulated. Many in the government recognised that the handloom industry helped address a significant portion of unemployment in independent India.

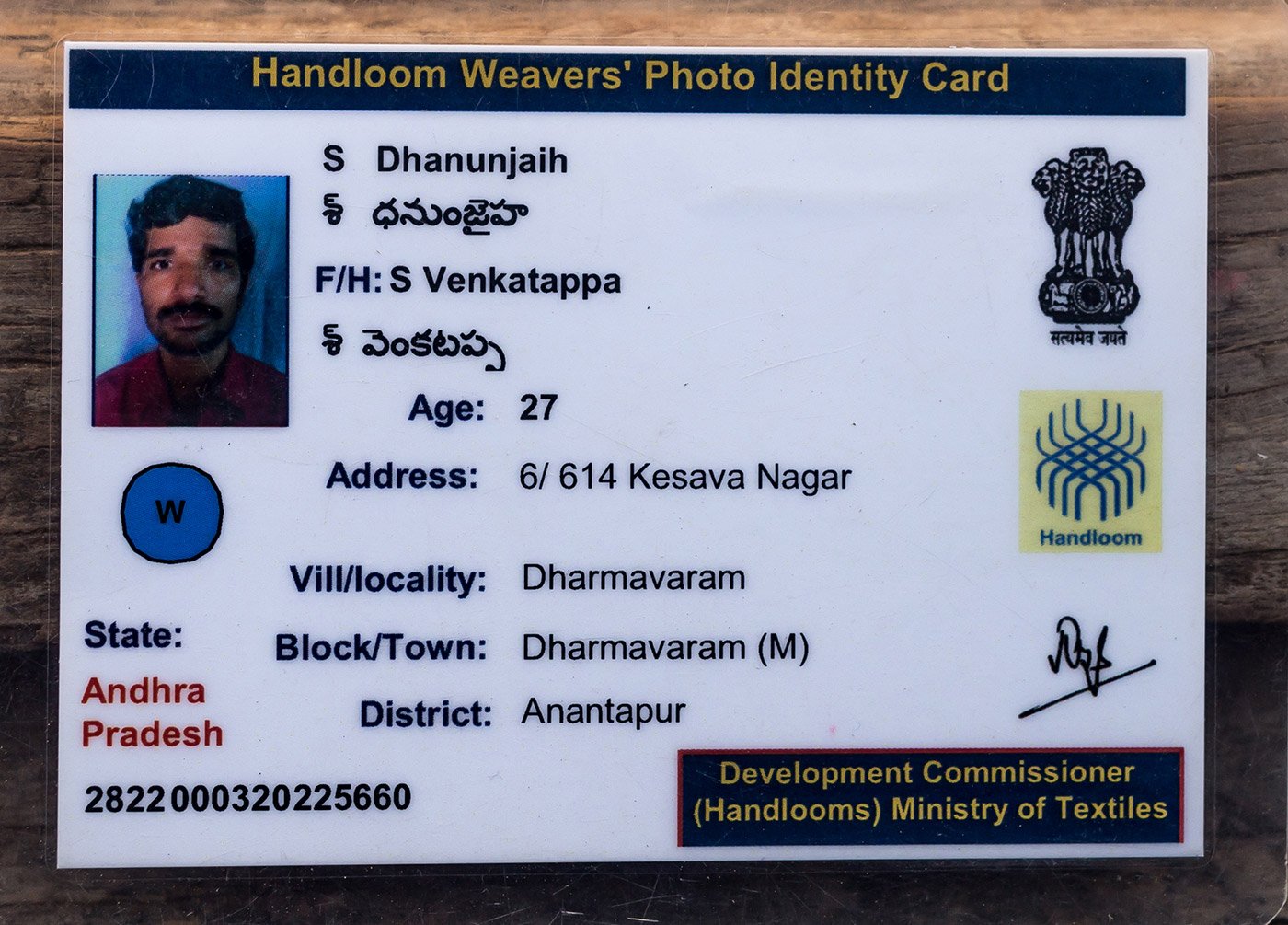

Dhanunjaya’s identity card, locally called a 'Delhi Card' because it is issued by the central government

With the Handlooms (Reservation of Articles for Production) Act of 1985, the restrictions over the industrial production of clothes were lifted, while reserving certain products. But this too was slowly diluted, and the list of 22 handloom products protected under this Act had shrunk to 11 by the 1990s. Handlooms moved to the Ministry of Textiles, which also managed powerlooms and textile mills. Instead of a policy that prioritised handlooms, the ministry started seeing the sector on a par with powerlooms.

In an article, titled ‘1985 textile policy – end of handloom industry’ published in the Economic and Political Weekly in 1985, L. C. Jain, former member of the Planning Commission, wrote: “They [the powerloom and mill lobbies] have hailed these [changes in policies] as a harbinger of ‘hope’ and a ‘bold’ departure from the past. It did require some boldness, if that is the virtue we are seeking, to have reversed the textile policy rooted not only in freedom struggle and nurtured by Gandhiji and Rajaji, but also rooted in India’s socio-economic realities as recognised by the successive Five-Year Plans in the past.”

The entrance to Dharmavaram, once a thriving centre that attracted migrants to settle here as weavers

Around 1996, Dhanunjaya, then 15, moved to Somandepalli village, 50 kilometers from Dharmavaram, to learn the laatu maggam , a pit-loom. Pit-looms were more efficient than handlooms, but also extremely strenuous. Dhanunjaya wanted to prosper by weaving this loom.

His brother Kumar, nine years younger, wasn’t as passionate about weaving. "We don't know anything else," he said. "Our elders taught us only this occupation." After Kumar finished training as a weaver, he would go to Dhanunjaya for help. “He was very talented and knew all about techniques and designs.”

Shankara Kumar next to his brother Dhanunjaya’s grave

The slide downwards was gradual for Dhanunjaya. In 2005, when he got married, he inherited the loan of Rs. 30,000 rupees his father borrowed for his wedding. This didn’t shake Dhanunjaya’s will to weave and do well.

But by the late 1990s, powerlooms had crept into the villages around Dharmavaram, and by 2005 they started making the silk products reserved for weavers. Within a few years, powerloom products had swamped the markets. At the same time, the prices of raw materials were rising quickly due to the demand from the powerlooms. Unlike the weavers who purchased a few kilos of silk at a time, powerloom owners bought silk in tons.

One outcome was the ‘handloom buildings’ that sprang up in Dharmavaram around 2000. Weavers began working and living in buildings crammed with handlooms with CCTV surveillance and security guards.

Powerlooms, once heavily regulated, now openly operate in Dharmavaram

Kumar and many others sold their handlooms and began working on looms owned by others. “I feel it’s better to work as a labourer on another’s handlooms instead of on one’s own,” says S. Amarnath, a 29-year-old weaver. “If you have just one loom then there is high risk, if you have 10 handlooms the risk will be distributed.”

By now the weavers’ unions had also weakened and could no longer negotiate prices with the bulk buyers of silk products. Left with little negotiating heft, “it became increasingly hard to organise weavers for protests,” Ramanjaneyulu says.

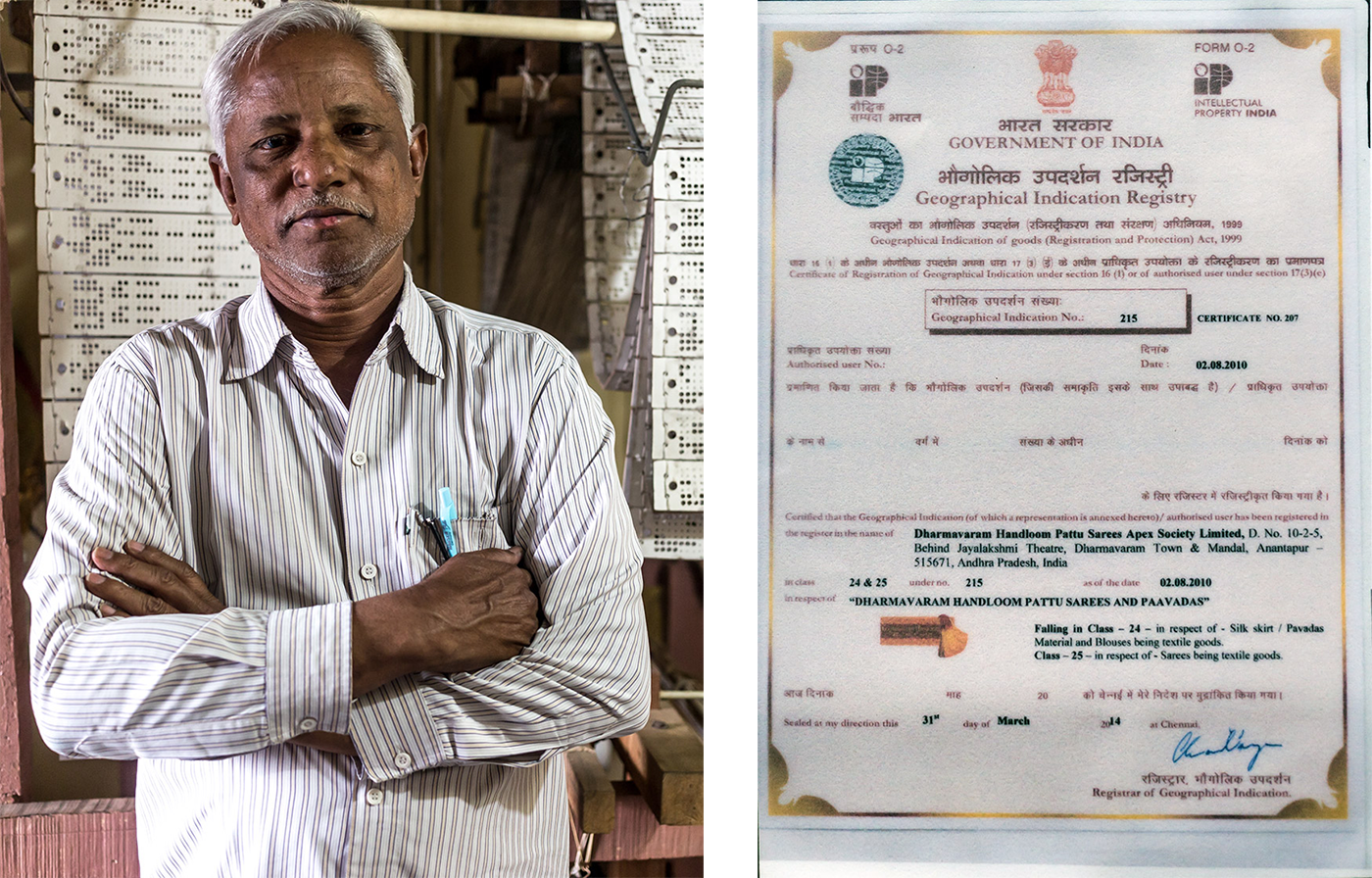

Pola Ramajineyulu, president of a weavers’ association, says that in the past 'people from all the other castes respected us because we taught weaving to everyone'. Right: The Geographical Indication Registry of Dharmavaram, which should ideally prevent copying of the location's signature silk sarees

In no time, the powerlooms also copied the sarees produced by handlooms and sold them in the same markets as handloom products, though Dharmavaram’s handloom pattu sarees and paavadas ('half-sarees') were given a GI (geographical indication) by the state government in 2010. The GI prevents copying and legally allows for only traditional manufacturing of Dharmavaram silk sarees.

The losses began to rise. Weavers who produced one silk saree in 4 to 7 days with help from their family members were forced to compete with powerlooms operated by one individual and churning out 2-3 sarees a day. Till the 1990s, weavers had changed their designs once in a few years. Now, they were pushed to change them every 3-4 months because powerlooms can store up to 64 designs in a computerised chip; for this they had to freeze the loom for 20 days and spend around Rs. 5,000 for the templates.

To stay afloat, the weavers started incurring debts. Many who could no longer repay their loans became – and remain – defaulters in bank records. The loan waiver schemes promised by various political parties continue to be delayed.

“We have incurred debts (from informal sources) for 5-6 years,” says Amarnath. “Whenever I went to the bank for a loan, I was asked to bring a politician or a well-known person to vouch for me. We don’t know anyone like that.” Amarnath’s father, S. Jagannath, borrowed Rs. 6 lakhs from moneylenders and relatives. Crushed by the stress of this loan, on the night of February 26, 2017, he hanged himself in Dharmavaram.

Dhanunjaya's family had been notified around 2012 by the Office of the Development Commissioner (Handloom) that they were eligible for a loan under the Weavers Credit Card scheme. But the bank didn't sanction the loan. "The bank managers think we don't pay them back," says Dhanunjaya's wife’s brother, Gaddam Sivashankar, who also applied for the loan that year.

Dhanunjaya’s brother-in-law, Gaddam Sivashankar, weaves on a pit-loom at his home in Dharmavaram

According to an internal government report, the banks in Anantapur district sanctioned loans worth Rs. 1808.51 lakhs to 4,857 weavers in 2012-13. This amount dropped to Rs. 47 lakhs, given to just 65 weavers in 2016, before the scheme was replaced by another in August 2016.

When the powerlooms were set up in Dharmavaram, Dhanunjaya started purchasing more handlooms in an effort to keep up. By 2013, he had four (each handloom costs around Rs. 50,000), and had spent large sums for two caesarean surgeries for his wife, S .Chandrakala . To keep up, he too borrowed from local moneylenders.

By 2015, Dhanunjaya was forced to sell three of his looms. And by then, he had started drinking regularly, perhaps due to the anxiety and pressure from moneylenders. Alcoholism, Ramanjaneyulu says, has been growing among the weavers in Dharmavaram.

In October 2016, determined to stop drinking, Dhanunjaya turned to Lord Ayyappa, who is believed to fulfil wishes if one follows a disciplined, ascetic lifestyle. "I have taken up Ayyappa maala [a 41-day observance]. All our problems will end now," he told his mother.

But by December, when the stress of the debt mounted, Dhanunjaya returned to alcohol. "Moreover, after demonetisation it was hard to rotate the debts," Kumar said. People in the villages often borrow money from friends or family to pay their old debts to retain the moneylender’s trust.

"People must have seen him drinking. He probably felt ashamed about drinking while on maala ," his mother, around 70, said. On the night of December 16, Dhanunjaya returned home while his wife was at her mother's place, and hanged himself next to the one handloom that remained in his house.

Not far from his home in Dharmavaram, there is a statue of Mahatma Gandhi spinning a charkha . The inscription below reads: ‘Without khadi , I am not there’.