“There is no such thing as a crisis in agriculture.”

Meet Darshan Singh Sanghera, vice president of Punjab’s powerful Arhtiyas Association. And boss of its Barnala district chapter. Arhtiyas are commission agents, a link between farmers and buyers of their produce. They arrange for the auction and delivery of harvested crop to the buyers. They are also moneylenders with a long history in that trade. In recent years, they’ve emerged as input dealers as well. All of which means they wield great control over farmers in this state.

The arhtiyas are also politically powerful. They count members of the legislative assembly amongst their brethren. In July last year, they honoured Chief Minister Amarinder Singh with the title of ‘Fakhr-e-Quam’ (‘Pride of the Community’). Local media termed the event “a mega felicitation function.” It came soon after the chief minister had said it would be difficult to waive off the debt owed by farmers to the arhtiyas .

As many as 86 per cent of farmer and 80 per cent of agricultural labour households are mired in debt, says a study on Indebtedness among Farmers and Agricultural Labourers in Rural Punjab. Its authors, researchers at Punjabi University, Patiala, say over a fifth of that debt was owed to commission agents and moneylenders. What’s more, the debt burden gets worse down the scale. It’s heaviest amongst marginal and small farmers. The study covered 1007 farmer and 301 agricultural labour households. Its field surveys in 2014-15 were spread across all regions of the state. Other studies too speak of deepening debt and mounting misery.

Darshan Singh Sanghera dismisses agrarian distress as “all due to the spending habits of the farmer. That is what lands them in trouble,” he says firmly. “We help them with money to buy inputs. Also, when they have weddings, medical and other expenses. When the farmer’s harvest is ready, he brings it and gives it to an ahrtiya . We clean the crop, bag it, deal with the government, the banks, the market.” The government pays the agents 2.5 per cent of the value of total procurement of wheat and paddy. The official side of their activity is governed by the Punjab State Agricultural Marketing Board. The farmers receive their payment through these commission agents. And all this is apart from the income the arhtiyas derive from moneylending.

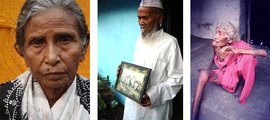

An agricultural labourer in Mansa. Farmers as well as labourers in Punjab are mired in debt, over a fifth of which is owed to arhtiyas

We reached Sanghera’s Grain Market office in Barnala town soon after visiting Jodhpur village in the same block. There, Ranjit and Balwinder Singh recounted the very public suicides of their relatives Baljit Singh and his mother Balbir Kaur within an hour after each other on April 25, 2016. “They were resisting the attachment of their land by an arhtiya who had arrived with a court order and some 100 police personnel in tow,” said Balwinder. “Plus, many officials of the local administration and several goondas of the arhtiyas .” Almost 150 people in all – to attach the family’s two acres of land.

“In this Jodhpur village alone,” says Balwinder, “there are some 450 households. Of these, just 15-20 are debt free.” And the debt has seen farmers losing land to arhtiyas .

“Relations between arhtiyas and farmers are not so bad,” says Sanghera. “And there is no crisis in farming. Look at me, I inherited just eight acres. Now I have 18. The media sometimes blow the issues out of proportion. Government compensation for suicides simply encourages more of them. If even one family gets compensation, it inspires others. Stop these compensations altogether and the suicides will stop.”

For him, the villains are the unions that defend farmers’ rights. And the worst offender is the Bhartiya Kisan Union (Dakonda). The BKU (D) is strong in this region and a tough nut to crack. Their members turn out in large numbers to block land attachments and seizures. Even when the arhtiyas have been accompanied by gun-toting underlings.

“Most arhtiyas have weapons,” concedes Sanghera. “But these are only used for self-defence. When you deal in large amounts of money, you need security, no? Mind you, 99 per cent of farmers are good people.” Apparently, the remaining one per cent are troublesome enough to warrant armed security all the time. He too owns a firearm. “It became necessary in the days of militancy in Punjab,” he explains.

Meanwhile, debt-driven suicides are mounting. No less than 8,294 farmers took their own lives between 2000 and 2015, says a study presented last year before the Vidhan Sabha’s Committee on Agrarian Suicides. The report, titled Farmer and Labourer Suicides in Punjab , says 6,373 agricultural labourers also killed themselves in the same period. And that was in just six of the state’s 22 districts, say its authors, researchers of the Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), Ludhiana. The study, commissioned by the state government’s revenue department, found that 83 per cent of all these suicides were largely debt-driven.

Teja Singh, arhtiya and former policeman, argues that half of the farmers’ suicides are not genuine

“Nobody is committing suicide in helplessness,” asserts Teja Singh. “Farming is doing well these last 10 years. Arhtiyas have in fact lowered lending rates.” Down to 1 per cent a month (12 per cent a year), he says. In village after village, though, farmers spoke of the rate being 1.5 per cent (18 per cent a year) or higher. Teja Singh is the arhtiya involved in the Jodhpur village battle that saw mother and son kill themselves in full public view. “Only 50 per cent of all these farm suicides are genuine,” he scoffs.

However, he speaks with refreshing candour of arhtiya politics. There are factions, yes. “But whichever party comes to power, their man becomes president of our association.” The present state chief is with the Congress. Before the elections it was an Akali man. Teja Singh’s son Jaspreet Singh feels the commission agents are being maligned. “Ours is just another profession,” he says. “We are unfairly given a bad name. After our [Jodhpur] case, about 50 arhtiyas quit the trade.”

However, Jaspreet is pleased with the media. “The local press has been very good to us. We have faith in the media. We will not be able to repay them. No, we gave no money to anyone for favourable coverage. The Hindi press came to our rescue [when criminal cases were filed against them after the Jodhpur incident]. We obtained bail from the High Court quicker than we might otherwise have.” He feels the Hindi papers are more supportive since they back the trader community. The Punjabi press, he laments, tends to be closer to the landed classes.

The state government’s October 2017 loan waiver was limited, layered and conditional. It applies to what farmers owe cooperative banks and public sector or even private banks. And that too, has unfolded in a narrow, restricted way. In its 2017 election manifesto, the Congress party had promised a complete “waiver of agricultural debt of farmers.” And that the Punjab Settlement of Agricultural Indebtedness Act of 2016 would be tweaked to make it “more comprehensive and effective.” To date the government has not waived a paisa of the Rs. 17,000 crore farmer debt owed to the arhtiyas .

A 2010 study recommended that this “system, in which the payment of the farmers’ produce is made through the commission agents, should be scrapped.” The study on Commission Agent System in Punjab Agriculture by researchers of the PAU, Ludhiana, called for “direct payment to the farmers for the procurement of their produce.”

The story of commission agents and farmers has a resonance across the country. But there is a novel element here. Unlike most of their fraternity elsewhere, Darshan Singh Sanghera, Teja Singh and many like them are not from the Bania or other trader castes. They are Jat Sikhs. Jats are late entrants to the trade. But they’re doing well. Today, of the 47,000 arhtiyas in Punjab, 23,000 are Jats. “In the cities, we are not the biggest group, says Sanghera. “I got into this trade in 1988. Even 10 years later, there were just 5-7 Jat arhtiyas in this mandi . Today there are 150 shops, of which one-third are Jats. And in the smaller markets on the periphery, we are in a majority.”

The portraits on Darshan Singh Sanghera’s office wall are an eclectic mix

Most of the Jats began as junior partners to Bania arhtiyas . Then branched out on their own. But why would the Banias want Jats as partners at all? When it comes to money recovery and the risk of rough stuff, says Sanghera, “the Bania arhtiyas get scared.” The Jat arhtiyas are not so squeamish. “We get the money back,” he says calmly.

A group of mostly Jat farmers I recounted this story to in Muktsar district laughed raucously. “He was telling you the truth,” some of them said. “Jats won’t recoil from rough stuff. The Banias will.” The junior partners are on their way to being big brothers in the trade.

But perhaps the impact of that partnership with the Banias still shows in limited ways. In Sanghera’s office, we ask his son Onkar Singh about the five portraits on the wall. The first two are of Guru Gobind Singh and Guru Nanak. The last two are of Guru Hargobind and Guru Tegh Bahadur. The central one in this line up of five is of Shiva and Parvati with a baby Ganesha. How did that come to be?

“We have entered this profession, we have to adapt to its ways,” said Onkar.