R. Krishna is something of a celebrity in Velaricombai village of Kotagiri panchayat , Tamil Nadu. He has acquired local renown for his mastery of traditional Kurumba painting techniques. The style is geometric and minimalist, and subjects include harvest festivals, religious rituals, honey gathering expeditions and other practices of the Adivasis of the Niligiris.

We met him somewhere deep in the forest, a two-hour uphill hike past verdant tea fields and precariously laden jackfruit trees. Rounding a hairpin bend on a remote mountain trail, my two companions and I staggered into a sudden patch of sunlight and squarely into Krishna’s path.

He bore us no ill will for our unceremonious arrival and was quite happy to sit down in the clearing to divulge the contents of his portfolio. An orange plastic accordion folder in a weathered yellow sack turned out to contain several dozen newspaper clippings, photographs and samples of his artwork. He carries the parcel with him everywhere, presumably in anticipation of just such an encounter.

Left: A photograph of a photo of Krishna while painting. Right: One of his completed artworks

“One time, the district collector got

interested in some of my paintings and bought [them],” Krishna, 41, tells us

in the Badaga language. It was, he says, one of the proudest moments of

his career.

Krishna is among the last few in a long line of Adivasi artists. Many Kurumbas believe their ancestors are responsible for the striking cliff art of Eluthupaarai, an archaeological site said to be 3,000 years old, located three kilometres from Velaricombai. “Before, we lived near Eluthupaarai, in the interior of the forest,” Krishna says. “You can only find these paintings [among the] Kurumbas.”

Krishna’s grandfather too was a painter of some renown who helped decorate several local temples, and Krishna began learning from him at the age of five. Today, he carries on his grandfather’s legacy, with a few modifications: while his predecessors painted with sticks on vertical rock faces, Krishna employs brushes on canvas and handmade paper. He does, however, perpetuate the use of organic, homemade paints, which, our translator tells us, are far more vivid and long lasting than their chemical counterparts.

Krishna is among the last few in a long line of artists in his Adivasi community

Krishna’s 8x10 originals retail for approximately Rs. 300 in the gift shop of Last Forest Enterprises in Kotagiri, an organisation that sells honey and other locally-produced wares. It takes him about a day to produce two paintings, and he sells between 5-10 a week. He also paints greeting cards and bookmarks, and is frequently called upon to decorate the walls of local homes and businesses in the Kurumba style. He occasionally offers classes in the art to Kurumba children. All told, his artistic pursuits generate Rs. 10,000-15,000 per month.

He supplements this by joining honey gathering expeditions, earning Rs. 1,500- 2,000 per month, in season. The practice involves dangling several hundred feet above ground to smoke out honeybees nestled in cliffside crevices, then harvesting the liquid gold they leave behind. Although rare, fatalities do occur during these excursions. As a chilling reminder of the worst that can befall a hunt, the clearing where we set up camp afforded a straight-line view of a cliff where someone plummeted to his death several years ago. Out of respect for their fallen comrade, the honey hunters now avoid that spot entirely. Thankfully, the worst injury Krishna himself has sustained while gathering honey is a bee sting on his nose.

Before we parted, Krishna gave us instructions for locating his home in the village of Velaricombai and invited us to drop by. We ventured there a few hours later and received a warm welcome from his wife Susila, and a rather less enthusiastic reception from his two-year-old daughter Gita.

Left: Verdant tea estates on the way to Velaricombai, R. Krishna's village. Right: The cliff where a Kurumba honey gatherer fell to his death several years ago

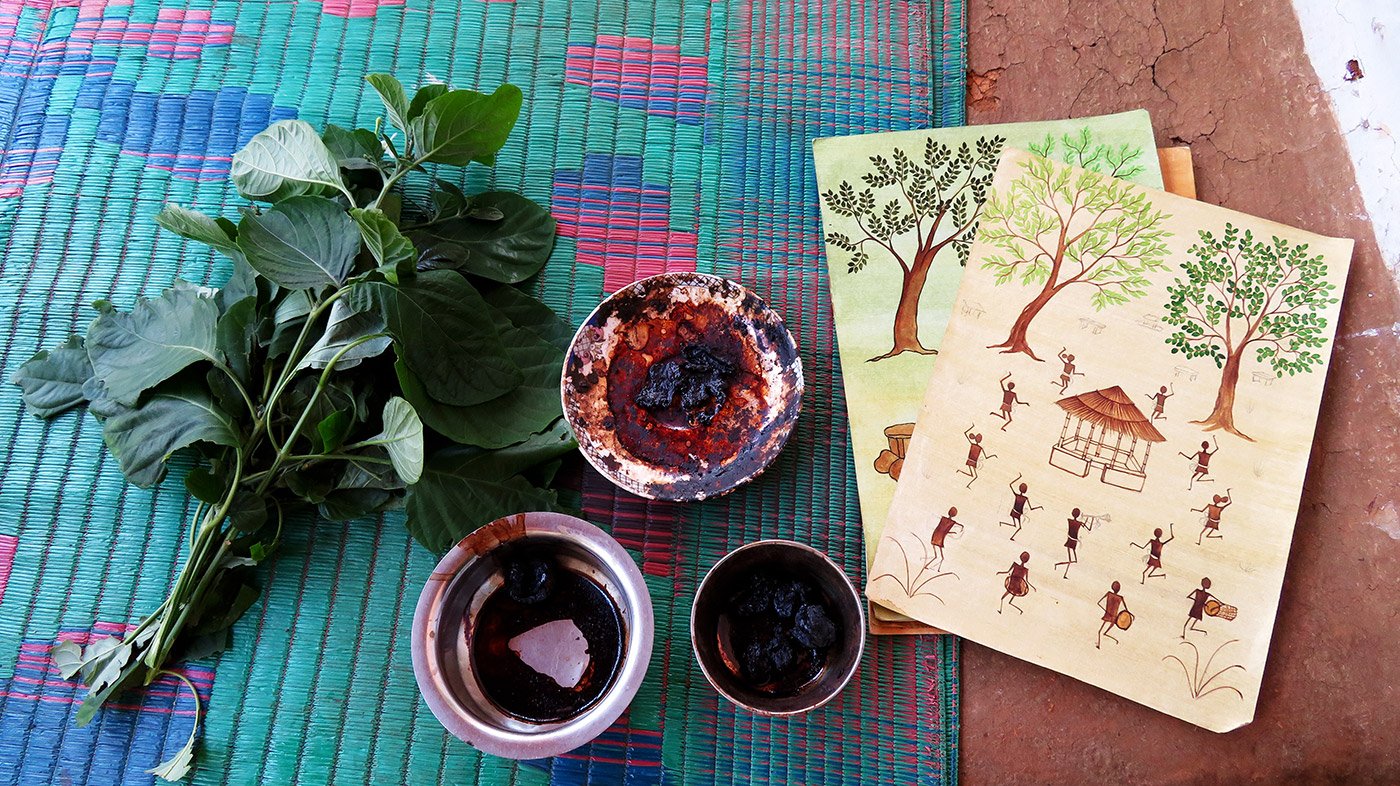

Susila graciously showed us samples of his organic paints, which Krishna concocts from forest materials according to traditional recipes. The rich, earthy tones characteristic of his artwork can be directly attributed to these sylvan ingredients. Green comes from kattegada leaves; various shades of brown come from the sap of the vengai maram tree. Karimaram bark yields the colour black, kaliman sand offers yellow, and buriman sand provides a startlingly bright shade of white. Reds and blues are rarities in Kurumba paintings.

Krishna is adamant that Kurumba art continues for generations to come. For him, painting is not only a personal passion, but also as a means of perpetuating Kurumba culture, which he feels is rapidly eroding. When asked what advice he would relay to young artists, he replies, “You can go to universities if that’s your wish, but don’t move beyond our culture. Fast food is not a good thing – eat what the ancients did. Continue these paintings, continue honey hunting... All medicines are right here in the forest.”

Krishna's daughter Gita peeps shyly around a doorframe. Right: His wife Susila with Gita

Krishna is acutely conscious of the precarious tango between the ancient and the modern; indeed, as we were chatting, his cell phone rang, flooding the little clearing with the sort of music you might hear in a Mumbai nightclub. We all laughed and resumed the interview, but for a moment, the serenity of the remote mountainside was shattered.

Sincere thanks to Saravanan Rajan, a marketing executive at Last Forest Enterprises, and my translator and guide in the Nilgiris. Many thanks also to Audra Bass, an AIF Clinton Fellow affiliated with Last Forest Enterprises, who facilitated my stay in Kotagiri and accompanied me on field visits.